Armstrong Gibbs

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs (10 August 1889 – 12 May 1960) was a prolific and versatile English composer, best known for his output of songs. Gibbs also devoted much of his career to the amateur choral and festival movements in Britain. He attained a high level of popularity: his work "Dusk" was requested by Princess Elizabeth (the present Queen Elizabeth II) on her eighteenth birthday.

Biography

Early years and education

Gibbs was born in Great Baddow, a country village near Chelmsford in Essex, England on 10 August 1889. His maternal grandfather, a Unitarian minister who wrote a number of songs in spite of being musically untrained, was his closest musical relation. His father, David Cecil Gibbs, was the head of the well-known soap company D & W Gibbs, (Better known later for GIBBS S R Toothpaste which is now part of the Unilever group, founded by C. A. Gibbs's grandfather.) Gibbs's mother, Ida Gibbs (née)[1] Whitehead, died on the 12th August 1891 when Gibbs was only two, having given birth to a stillborn son. While Gibbs had many privileges in his childhood owing to his father's wealth, he was deprived of any permanent mother figure, having been raised by a nurse and five maiden aunts in three month rotations. Gibbs's childhood was further troubled by his father's method of child-rearing; he sought to “toughen up” his son by making him sleep in the attic, forcing him to ride and jump a pony at the age of six, and throwing him into deep water in order to learn to swim.[2] This manifested itself later in Gibbs's adulthood as agoraphobia and other nervous troubles. His father re-married on the 16th September 1897 when he was 46 to Mary Elizabeth Hart who was half his age.

Gibbs's musical talent appeared early in life: an aunt discovered that he had perfect pitch at age three. He was also improvising melodies at the piano before he could speak fluently and he wrote his first song at the age of five. While family members insisted that Gibbs should attend some kind of music school abroad, Gibbs's father was insistent that Gibbs have a proper British education to prepare him for running the family business. Therefore, Gibbs attended the Wick School, a preparatory school in Brighton beginning in 1899. Gibbs's facility as a student, specifically his talents in Latin, won him a scholarship to Winchester College in 1902 where he specialized in history. However, while at Winchester, Gibbs began music studies in earnest, taking lessons in harmony and counterpoint with Dr. E. T. Sweeting. From 1908-1911 he attended Trinity College, Cambridge on a scholarship as a history student. He continued his studies at Cambridge in music through 1913 studying composition with Edward Dent, Cyril Rootham and Charles Wood. It was at Cambridge that he also studied organ and piano; however, his tendency to “drift off into improvising was too strong,”[3] and it became apparent that his future did not lie in musical performance.

After earning his Mus. B from Cambridge in 1913, Gibbs became a preparatory school teacher. He taught at the Copthorne School in Sussex for a year, then at the Wick School (his alma mater) beginning in 1915. During World War I, he continued to teach at the Wick since he was considered unfit for military service. At the Wick, Gibbs taught English, history and the classics, and also led a choir which became “very keen and competent.”[4] In 1918, he married Miss Honor Mary Mitchell and had his first child, a son, in the following year.

Musical career

Early in his adulthood, Gibbs found little time to compose because of teaching duties, and publishers had rejected the few songs he had found time to write. Gibbs was considering becoming a partner with the Wick School.[5] However, Gibbs was awarded a commission in 1919 to write a musical for the school on the occasion of the Headmaster's retirement. Two significant incidents that altered his career came from this project. The first was the formation of his friendship with poet Walter de la Mare, who accepted Gibbs's offer to write the text for the play. The second was that the conductor of this production was none other than Adrian Boult who convinced Gibbs to take a leave of absence from teaching and study music at the Royal College of Music for one year. At the Royal College, Gibbs studied with Ralph Vaughan Williams, Charles Wood, and Boult himself. With the help of the Director, Sir Hugh Allen, he managed to have some of his songs published thus initiating his musical career.[6]

In the early 1920s, Gibbs and his family returned to Danbury, Essex, just a few miles from where Gibbs spent his childhood. Here, Vaughan Williams was their neighbor for a short time. Later, Gibbs had a house built in Danbury, named Crossings, where he lived until World War II.[7]

Also in the early 1920s, Gibbs received two significant commissions for stage music, won the Arthur Sullivan Prize for composition, and was regularly getting his music published and performed.[8] In 1921, he was invited to join the staff of the Royal College of Music where he taught theory and composition until 1939.[9] In 1921, Gibbs also founded the Danbury Choral Society, an amateur choir that he conducted until just before his death. In 1923, Gibbs was asked to adjudicate at a competitive musical festival in Bath and quickly found that he had a penchant for this type of work. Within a few years he became one of the best-known judges in England. From 1937 to 1952,[10] he was the Vice-chairman of the British Federation of Musical Festivals, a job that he regarded as one of his most important.[11] In 1931, Gibbs was awarded the Doctorate in Music at Cambridge for composition.

During World War II, Crossings, his home, was commandeered for use as a military hospital, so Gibbs and Honor moved to Windermere in the Lake District.[12] Although the competitive festivals came to a temporary halt during the war, he continued to be highly involved in musical performance; Gibbs formed a thirty-two voice male choir and co-led a county music committee that focused on producing evening concerts. His son was killed on active service in November 1943 in Italy during World War II. After the war, Gibbs and Honor returned to Essex to a small cottage near Crossings called “The Cottage in the Bush.” The competitive festivals resumed. After his retirement from his position as Vice-chairman in 1952, Gibbs continued to write music with more focus on large-scale works including a cantata and a choral mime. While these late compositions were still receiving praise from audiences and participants, they were not nearly as successful as his smaller works.[13] Honor died in 1958, and Gibbs died of pneumonia in Chelmsford on 12 May 1960.

Music

Style and output

While Gibbs exhibited musical talent early in his life, he came to composition as a relative latecomer, not officially starting a career until his thirties.[14] Gibbs is best known for his output of songs; he also wrote a considerable amount of music for the amateur choirs that he conducted. Unfortunately, because of Gibbs's association with the amateur musicians, some have dismissed Gibbs's work as being “lightweight and even trivial.”[15] Others have looked upon this quality positively; in the words of Rosemary Hancock-Child, “as a miniaturist, he excelled.”[16]

Gibbs was writing in an era in which European masters such as Mahler, Elgar and Puccini were still writing in a traditional style, but younger composers were searching for a new idiom that lay outside tonality. Gibbs himself had little regard for the aural effect of serialism and atonality although he made an effort to hear new works.[17] Curiously, he also cautioned that “the dissonances of one generation become the consonances of the next.”[18] Gibbs's personal sound was far more influenced by “lighter forms of entertainment, popular song, and British folk song” than it ever was by the avant-garde.[19] He admired Debussy; he was repelled by Wagner and Schoenberg. Gibbs accepted tradition and did not seek to break new ground.[20]

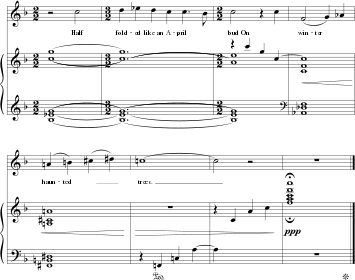

Gibbs's melodic style often features 1) phrases begun mid-bar rather than on a strong beat, 2) flattened 7ths and other modal inflections, 3) arched phrases, 4) syllabic text setting, and 5) lengthening of words to make them more prominent.[21] Sometimes he would also alter the time signature briefly to accommodate the phrasing of the words. These features are present in his song “The Sleeping Beauty,” excerpted below. The two phrases begin on weak beats rather than down beats; the first begins on the second beat in the first measure and the “and” of the second beat in the third measure, respectively. Both phrases are also arched in form. While it is clear by the end of the passage that the tonic key is F major, the chromatic alterations made in the first five measures may suggest C minor or F mixolydian. Also, with the exception of the words “winter” and “haunted,” the text setting is mostly syllabic; a 3/2 bar is also used to accommodate the words in the first phrase.

| Example 6.1 |

|---|

|

Gibbs's melodies “lie comfortably on the voice,”[22] though the melodies are not always easy to pitch against the accompaniment. However, voice and piano are interdependent in his songs; the vocal line usually relies on the accompaniment's harmonies for context. Because of his amateur keyboard ability, the accompaniments to his songs are usually approachable.[23]

Songs

Gibbs's reputation as a songwriter largely lies in his natural gift for text setting.[24] He insisted on giving priority to the words over the music and had very clear musical ideas on what a song should be: short, possessing a dominant theme, and “[creating] an aura as music is able to heighten.”[25]

Gibbs set poems by over fifty different poets, but his best works feature poems by Walter de la Mare, a lifelong friend whom he first worked with in person on his commission from Wick School in 1919. In fact, thirty-eight of his one hundred fifty songs (approximately) are texts by de la Mare. Fellow composer and friend, Herbert Howells, commented in a letter to Gibbs in 1951 that, “You’ve never yet failed in any setting you’ve done of beloved Jack de la Mare’s poems.”[26] De la Mare's poem, “Silver,” was set twenty-three times by various composers; however, according to Stephen Banfield, Gibbs's setting of this text may be regarded as the “definitive” version.[27] The only other poet that brought out the best in Gibbs's musical craft was Mordaunt Currie (1894-1978), a baronet who lived at Bishop Witham in Essex, not far from Gibbs's residence. Gibbs set seventeen texts by Currie. In choosing subject matter, Gibbs avoided the lofty ideas of unrequited love and death and focused more on nature, magic and the world seen from a child's point of view.[28]

Gibbs wrote his best songs early in his career between 1917-1933.[29] Later in his career, his inspiration came intermittently though his zest for composing continued even to the end of his life.[30] Not all of Gibbs's songs were successful. Some contain no significant music, others come off as pedantic, sentimental, or too predictable.[31]

Other works

Gibbs also wrote stage music, three symphonies, sacred works, and chamber music.[32] The second symphony is the hour-long choral symphony, "Odysseus", which is perhaps his greatest work. In addition, Gibbs wrote quite a number of settings for choir, mostly for schools and the amateur ensembles he worked with though they were not strong enough works to earn a place in the repertoire.[33]

Gibbs was also a fluent writer for strings, in particular the string quartet, writing more than a dozen;[34] many of his early songs have string accompaniments, and his slow waltz "Dusk" for orchestra and piano became extremely popular, earning him more royalties than any of his other works combined.[35]

Works

Complete list of compositions

Writings

The Festival Movement (London, 1946)

“Setting de la Mare to Music,” Journal of the National Book League no. 301 (1956), 80–81.

Common Time, 1958 [unpublished autobiography]

Selected Recordings

National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Andrew Penny. Symphonies Nos. l & 3. Marco Polo, 1993. 8.223553.

Guildhall Strings Ensemble, Robert Salter. Dale & Fell. Hyperion, 1999. 67093. (Includes the Prelude, Andante & Finale op 102, Dale and Fell, the Threnody for Walter de la Mare, A Spring Garland op 84, Almayne op 71, and the Suite for Strings)

Guildhall Strings Ensemble, Robert Salter. Peacock Pie. Hyperion, 2002. 67316. (Includes the Peacock Pie suite for string orchestra and piano, and the Concertino for piano and string orchestra, op 103)

Hancock-Child, Nik (baritone) and Rosemary Hancock-Child (piano). Songs. Marco Polo, 1993. 8223458.

Reibaud, Patricia (violin), Mikhail Istomin (cello) and Igor Kraevsky (piano.) The Three Graces. Minstrel, 2002. B000066TGA.

McGreevy, Geraldine (soprano), Stephen Varcoe (baritone) and Roger Vignoles (piano). Songs. Hyperion, 2003. A67337. (Includes Country Magic op 47, The Yorkshire Dales, op 58, The Three Graces op 92, Piano Trio in D, op 99)

London Piano Trio. Armstrong Gibbs, Complete Piano Trios. Altamira, 2006. ABI230105.

BBC Concert Orchestra, London Oriana Choir. Odysseus, choral symphony in four movements. Dutton Epoch, 2008. CDLX7201.

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, Martin Yates, Jonathan Small (oboe). British Oboe Concertos, Dutton Epoch, 2010. CDLX7249. (Includes Concerto for oboe and orchestra, op 48)

Atchison, Robert (violin) Dugnik, Olga (piano). Complete Works for Violin and Piano. Guild, 2010. GMCD 7353

Peter Cigleris (clarinet), Antony Gray (piano). English Fantasy. Cala, 2013. CACD77015. (Includes Three Pieces for clarinet and piano)

BBC Concert Orchestra, Ronald Corp. Cecil Armstrong Gibbs, Orchestral Works, Dutton Epoch, 2016. CDLX7324 (Includes Crossings op 20, The Enchanted Wood op 25, A Vision of Night op 38, Dusk, Suite in A for violin and orchestra, The Cat and the Wedding Cake, Four Orchestral Dances)

External links

- Images of Armstrong Gibbs at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Armstrong Gibbs Society Official Website

- Free scores by Armstrong Gibbs at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Recording of "Dusk" on YouTube

- Danbury Church including Gibbs' monument

- Armstrong Gibbs: A Countryman Born and Bred by Angela Aries, Lewis Foreman and Michael Pilkington. EM Publishing, 2014 (PDF download)

Notes

- Richard Gibb family Remembrancer

- Ann E. Rust, “Cecil Armstrong Gibbs: A Personal Memoir,” The Journal of the British Music Society 11 (1989): 46.

- Rosemary Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker: The Life and Songs of C. Armstrong Gibbs (London: Thames, 1993), 16.

- Rust, “A Personal Memoir,” 48.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 19.

- Donald Brook, Composers’ Gallery: Biographical Sketches of Contemporary Composers (London: Rockliff, 1946), 66.

- Rust, “A Personal Memoir,” 49.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 21.

- Brook, Composers Gallery, 66.

- Stephen Banfield and Ro Hancock-Child, “Gibbs, Cecil Armstrong,” in Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press, 2013—), accessed 17 September 2013, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/11093.

- Brook, Composers Gallery, 67.

- Rust, “A Personal Memoir,” 52.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 31.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 53.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 26.

- Ro Hancock-Child, “Gibbs, Cecil Armstrong,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004—), accessed 12 October 2013, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/67640.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 16.

- Brook, Composers Gallery, 68.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 36.

- Trevor Hold, “Armstrong Gibbs,” in Parry to Finzi: Twenty English Song Composers (Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2002), 252.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 43.

- Hold, Song Composers, 254.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 48.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 37.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 37.

- Stephen Banfield, Sensibility and English Song (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 222.

- Banfield, Sensibility, 214.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 38.

- Hold, Song Composers, 252.

- Hancock-Child, A Ballad Maker, 73.

- Hold, Song Composers, 260-261.

- The Armstrong Gibbs Society Website, “His Music,” accessed 28 September 2013, http://www.armstronggibbs.org/index.html Archived 2013-10-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- Banfield, Sensibility, 223.

- The Armstrong Gibbs Society Website, “His Music.”

- Rust, “A Personal Memoir,” 54.