Liepāja

Liepāja (pronounced [liepaːja] (![]()

Liepāja | |

|---|---|

City | |

Art Nouveau architecture in Liepāja. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Liepāja Location of Liepaja in Latvia  Liepāja Liepāja (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 56°30′42″N 21°00′50″E | |

| Country | |

| Town rights | 1625 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jānis Vilnītis |

| Area | |

| • Total | 68.0 km2 (26.3 sq mi) |

| • Water | 10.87 km2 (4.20 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 14 m (46 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 68,535 |

| • Density | 1,000/km2 (2,600/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | LV-34(01-13); LV-3414; LV-34(16–17) |

| Calling code | +371 634 |

| Number of city council members | 15 |

| Website | www |

In the 19th and early 20th century it was a favourite place for sea-bathers, with the town boasting a fine park, many pretty gardens and a theatre.[1] Liepāja is however known throughout Latvia as "City where the wind is born", likely because of the constant sea breeze. A song of the same name (Latvian: "Pilsētā, kurā piedzimst vējš") was composed by Imants Kalniņš and has become the anthem of the city. Its reputation as the windiest city in Latvia was strengthened with the construction of the largest wind farm in the nation (33 Enercon wind turbines) nearby.

The coat of arms of Liepāja was adopted four days after the jurisdiction gained city rights on 18 March 1625.[2] These are described as: "on a silver background, the lion of Courland with a divided tail, who leans upon a linden (Latvian: Liepa) tree with its forelegs". The flag of Liepāja has the coat of arms in the center, with red in the top half and green in the bottom.[2]

One of the very few surviving films documenting the mass murder of Jews during the first stages of the Holocaust is a short film by a German soldier who witnessed the massacre of Liepāja Jews in July 1941 near the city's lighthouse.[3]

Names and toponymy

It is said that the first settlement at the location of modern Liepāja was known by the name Līva from the name of the river Līva on which Liepāja was located. The name was derived from the Livonian word Liiv meaning "sand". The oldest written text mentioning Līva village (Villa Liva) is the treaty of bishop of Courland and the master of the Livonian Order dated 4 April 1253. In 1263, the Teutonic Order established a town which they called Libau in German. The Latvian name Liepāja was mentioned for the first time in 1649 by Paul Einhorn in his work Historia Lettica. A Russian name from the time of the Russian Empire was Либава[4] (Libava) or Либау (Libau), although Лиепая (Liepaya), a transliteration of Liepāja, has been used since World War II.

Some other names for the city include Liepoja in Lithuanian,[4] Lipawa in Polish[4] and ליבאַװע (Libaveh) in Yiddish.

History

Early history

It is said that the original settlement at the location of modern Liepāja was founded by Curonian fishermen from Piemare as Līva, but Henry (Henricus Lettus) of Livonia, in his famous Chronicle, makes no mention of the settlement. The Teutonic Order established a town which they called Libau here in 1263, followed by Mitau two years later. In 1418 the village was sacked and burned by the Lithuanians.[5]

Livonian confederation

During the 15th century, a part of the trade route from Amsterdam to Moscow passed through Līva, where it was known as the "white road to Lyva portus". By 1520 the river Līva had become too shallow for easy navigation, and development of the city declined.

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

In 1560, Gotthard Kettler, first Duke of Courland and Semigallia, loaned all the Grobiņa district, including Libau, to Albert, Duke of Prussia for 50,000 guldens. Only in 1609 after the marriage of Sofie Hohenzollern, Princess of Prussia, to Wilhelm Kettler did the territory return to the Duchy. During the Livonian War, Libau was attacked and burnt by the Swedes.

In 1625, Duke Friedrich Kettler of Courland granted the town city rights, which were affirmed by King Sigismund III of Poland in 1626, although under what legal authority Sigismund had is debatable. Under Duke Jacob Kettler (1642–1681), Libau became one of the main ports of Courland as it reached the height of its prosperity. In 1637 Couronian colonization was started from the ports of Libau and Ventspils (Windau). Kettler was an eager proponent of mercantilist ideas. Metalworking and ship building became much more developed, and trading relations developed not only with nearby countries, but also with Britain, France, the Netherlands and Portugal.

In 1697–1703 a canal was cut to the sea and a more modern port was built.[6] In 1701, during the Great Northern War, Libau was captured by Charles XII of Sweden, but by the end of the war, the city had returned to titular Polish possession.[7] In 1710 an epidemic of plague killed about a third of the population. In 1780 the first Freemasonry lodge, "Libanons," was established by Provincial Grand Master Ivan Yelagin on behalf of the Provincial Lodge of Russia; it was registered as number 524 in the Grand Lodge of England.[8]

Russian Empire

Courland passed to the control of the Russian Empire in 1795 during the third Partition of Poland and was organized as the Courland Governorate of Russia. Growth during the nineteenth century was rapid. During the Crimean War, when the British Royal Navy was blockading Russian Baltic ports, the busy yet still unfortified port of Libau was briefly captured on 17 May 1854 without a shot being fired, by a landing party of 110 men from HMS Conflict and HMS Amphion.[9]

In 1857 an Imperial Decree provided for a new railway to Libau,[10] and the same year the engineer Jan Heidatel developed a project to reconstruct the port. In 1861–1868 the project was realized – including the building of a lighthouse and breakwaters. Between 1877–1882 the political and literary weekly newspaper Liepājas Pastnieks was published – the first Latvian language newspaper in Libau.[11] In the 1870s the further rapid development of Russian railways, especially the 1871 opening of the Libava-Kaunas and the 1876 Liepāja–Romny Railways, ensured that a large proportion of central Russian trade passed through Libau.[12] By 1900, 7% of Russian exports were passing through Libau. The city became a major port of the Russian Empire on the Baltic Sea, as well as a popular resort. During this time of economic expansion, the city architect Paul Max Bertschy provided the design for many of the city's both public and private buildings, making an imprint on the architecture which can still be seen today.[13]

On the orders of Alexander III, Libau was fortified against possible German attacks. Fortifications were subsequently built around the city, and in the early 20th century, a major military base was established on the northern edge. It included formidable coastal fortifications and extensive quarters for military personnel. As part of the military development, a separate port was excavated for exclusively military use. This area became known as Kara Osta (War Port) and served military needs throughout the twentieth century.

Early in the twentieth century, the port of Libau became a central point of embarkation for immigrants traveling to the United States and Canada. By 1906 the direct ship service to the United States was used by 40,000 migrants per year. Simultaneously, the first Russian training school of submarine navigation was founded. In 1912 one of the first water aerodromes in Russia was opened in Libau.[14] In 1913, 1,738 ships entered Libau, with 1,548,119 tonnes of cargo passing through the port. The population had increased from 10,000 to over 100,000 within about 60 years.

World War I and War of Independence

Following the outbreak of World War I, the German cruiser SMS Magdeburg shelled Libau, and other vessels laid mines off the approaches to the port.[15] Libau was soon occupied by the German Army, on 7 May 1915, and in memory of this event, a monument was constructed on Kūrmājas Prospect in 1916 (destroyed by Bolsheviks in 1919). Libau's local government issued its own money for a while in this period – Libaua rubles. An advanced German Zeppelin base was constructed at Vaiņode, near Liepāja, with five hangars, in August 1915.[16] On 23 October 1915, the German cruiser SMS Prinz Adalbert was sunk by the British submarine HMS E8, 37 km (23 mi) west of Libau.

With the collapse of Russia and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the occupying German forces had a quiet time, but the subsequent collapse of the German Empire and the Allied denunciation of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty changed everything. Independence of the Republic of Latvia was proclaimed on 18 November 1918, and the Latvian Provisional Government under Karlis Ulmanis was created. Bolshevik Russia now advanced into Latvian territory and met little resistance here. Soon the Provisional Government and remaining German units were forced to leave Riga and retreated all the way to Liepāja, but then the Red offensive stalled along the Venta river. A Latvian Soviet Republic was announced. Latvia now became the main theatre of Baltic operations for the remaining German forces in 1919. In addition, a Landeswehr was formed to work in conjunction with the German forces.

In Liepāja, a coup organized by Germans took place on 16 April 1919 and Ulmanis government was forced to flee and was replaced by Andrievs Niedra.[17] The Ulmanis government found shelter on the steamship "Saratov" in Liepāja port. In May a British cruiser squadron arrived at Libau to support Latvian independence and requested the Germans to leave.[18]

During the war, the words of "The Jäger March" were written in Libau by Heikki Nurmio.

The German Freikorps, having recaptured Riga from the Bolsheviks, departed in late 1919 and, with some Polish assistance, the Bolsheviks were driven out of the Latvian hinterlands in early 1920.

1920–1940

During the interwar period Liepāja was the second major city in Latvia. In an attempt to put Libau 'on the map', on 31 January 1922 the Libau Bank was founded with significant new capital, transforming the old Libau Exchange Bank which had belonged to the Libau Exchange Association, and it eventually became the fourth largest of Latvia's joint stock banks. However, when a Riga branch of the bank was opened, the business centre of gravity shifted from Liepāja so that by 1923 its Riga 'branch' was responsible for 90% of the turnover. The German consul in Liepāja reported at the time that "Riga, the economic heart of the country, draws all business to itself." The Latvian government ignored the pleas of the Libau Exchange Association to frustrate this.[19] In 1935 KOD (Latvian: Kara ostas darbnīcas) started to manufacture the light aircraft KOD-1 and KOD-2 at Liepāja. However it became evident in this year that trade with the new Soviet Union had virtually collapsed.[20]

World War II

The ports and human capital of Liepāja and Ventspils were targets of Joseph Stalin. He signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact in part to gain control of this territory. When the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Latvia in 1940, it nationalized private property. Many thousands of former owners were arrested and deported to the gulag camps in Siberia.

In 1941 Liepāja was among the first cities captured by the 291st Infantry Division of Army Group North after Nazi Germany began Operation Barbarossa, its war against the Soviet Union. German Nazis and Latvian collaborators virtually exterminated the local Jewish population, which had numbered about 7,000 before the war. Film footage of an Einsatzgruppen execution of local Jews was taken in Liepāja.[21][3] Most of these mass murders took place in the dunes of Šķēde north of the city. Fewer than thirty Jews survived in Liepāja by the end of the war.

During the war, the German navy's U-boat crews received their torpedo training at Liepāja.

During the period 1944–1945, as the Soviet Union began its offensive to the Baltic Sea, Liepāja was within the "Courland Pocket". It was occupied by the Red Army on 9 May 1945. Thousands of Latvians fled as refugees to Germany. The city had been devastated during the war, and most of the buildings and industrial plant were destroyed.

Latvian SSR

On 25–29 March 1949, the Soviet Union organized a second mass deportation to Siberia from Liepāja. In 1950 a monument to Stalin was erected on Station square (Latvian: Stacijas laukums). It was dismantled in 1958 after the Party Congress that discussed his abuses.

During 1953–1957 the city center was reconstructed under the direction of architects A. Kruglov and M. Žagare.[6] In 1952–1955 the Liepāja Academy of Pedagogy building was constructed under the direction of A. Aivars. In 1960 the Kurzeme shopping centre was opened. During the Soviet administration, Liepāja was a closed city; even local farmers and villagers needed a special permit to enter it.

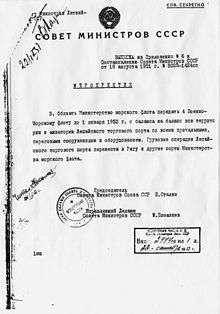

The Soviet military set up its Baltic naval base and nuclear weapon warehouses there; The Beberliņš sandpit was dug out to extract sand used for constructing underground warehouses. In 1967 the Soviets completely closed the port to commercial traffic. One third of the city was taken up with a Soviet naval base; its military staff numbered 26,000. The 14th Submarine Squadron of the USSR's Baltic Fleet (Russian: 14 эскадрилья ЛиВМБ ДКБФ, call sign "Комплекс") was stationed there with 16 submarines (Types: 613, 629a, 651); as was the 6th group of Rear Supply of the Baltic Fleet, and the 81st Design Bureau and Reserve Command Center of the same force.

In 1977 Liepāja was awarded the Order of the October Revolution for heroic defense against Nazi Germany in 1941. Five residents were awarded the honorary title Hero of Socialist Labor: Anatolijs Filatkins, Artūrs Fridrihsons, Voldemārs Lazdups, Valentins Šuvajevs and Otīlija Žagata. Because of the rapid growth of the city's population, a shortage of apartment houses resulted. To resolve this, the Soviet government organized development of most of the modern Liepāja districts: Dienvidrietumi, Ezerkrasts, Ziemeļu priekšpilsēta, Zaļā birze and Tosmare. The majority of these blocks were constructed of ferro-concrete panels in standard projects designed by the state Latgyprogorstroy Institute (Russian: Латгипрогорстрой). In 1986 the new central city hospital in Zaļa birze was opened.[22]

1990–present

After Latvia regained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union, Liepāja has worked hard to change from a military city into a modern port city (again appearing on European maps after the secrecy of the Soviet period). The commercial port was re-opened in 1991, and in 1994 the last Russian troops left Liepāja. Since then, Liepāja has engaged in international co-operation, has been associated with 10 twin and partner cities, and is an active partner in several co-operation networks. Facilities are being improved. The city is the location of Latvia's largest naval flotilla, the largest warehouses of ammunition and weapons in the Baltic states, and the main supply centre of the Latvian army.

The former closed military town has been transformed into the northern neighbourhood of Karosta, occupying a third of the area of the city of Liepāja and attracting tourists to the remaints of the military era.[23]

At the beginning of the 21st century, many ambitious construction projects were planned for the city, including a NATO military base, and Baltic Sea Park, planned as the biggest amusement park in the Baltic states. Most of the projects have not yet been realised due to economic and political factors. Liepāja's heating network was renovated with the cooperation of French and Russian companies: Dalkia and Gazprom, respectively. In 2006, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, a direct descendant of Jacob Kettler visited Liepāja. In 2010 the coal cogeneration 400 MW power plant was built in Liepāja with the support of the government.

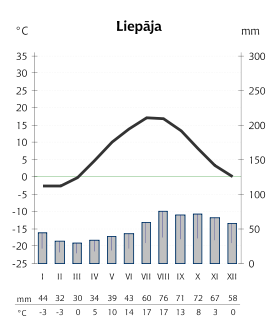

Climate

Liepāja enjoys a semi-continental climate noted as "Dfb" in the Köppen classification. The major factor influencing the weather in the region is the Baltic Sea, providing a relatively mild winter for its high latitude (although snowy) and a relatively cool summer. During the winter the sea around Liepāja is virtually ice-free. Although occasionally some land-fast ice may develop, it seldom reaches a hundred meters from the shore and does not last long before melting. The sea warms up fully only in the beginning of August, so the best bathing season in Liepāja is from August to September. Summers are more affected by the maritime climate than east-facing cities on similar latitudes in opposite Sweden, but winters are milder than inland areas to the east. Regular meteorological observations in the city have been conducted from 1857.

- Average temperatures:

- February: −3.1 °C (26 °F)

- July: 16.0 °C (61 °F)

- Absolute minimum of temperature: −33 °C (−27 °F)

- Absolute maximum of temperature: 34 °C (93 °F)

- Number of sunny days per year: 196

- Average speed of wind: 5.8 m/s (13 mph)

- Average annual norm of precipitation (mostly rain): 692 mm (27.2 in)

- Typical wind directions: in the winter – southern, in the summer – western.

| Climate data for Liepaja (1981–2010 temp and precipitation, 1961–1990 sun, humidity) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.7 (90.9) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.6 (92.5) |

30.7 (87.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

33.7 (92.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

0.3 (32.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.9 (−27.2) |

−31.6 (−24.9) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−32.9 (−27.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.5 (2.30) |

42.2 (1.66) |

46.5 (1.83) |

43.0 (1.69) |

41.2 (1.62) |

56.0 (2.20) |

72.1 (2.84) |

77.9 (3.07) |

81.9 (3.22) |

89.8 (3.54) |

87.8 (3.46) |

73.7 (2.90) |

762.9 (30.04) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.7 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 13.8 | 15.6 | 14.5 | 130.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87.2 | 85.8 | 82.8 | 76.3 | 75.7 | 77.4 | 78.9 | 78.5 | 80.5 | 82.9 | 87.4 | 86.9 | 81.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 34 | 64 | 130 | 187 | 273 | 295 | 279 | 248 | 173 | 103 | 43 | 28 | 1,857 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase (precipitation, humidity, extremes)[25] Source #3: Météo Climat[26] | |||||||||||||

Geography

Liepāja is situated on the coast of the Baltic Sea in the south-western part of Latvia. The westernmost geographical point of Latvia is located approximately 15 km (9 mi) to the south thus making Liepāja Latvia's furthest west city. Liepāja is situated between the Baltic Sea and Liepāja Lake with residential and industrial areas spreading north of the lake. The Trade Channel (Tirdzniecības kanāls) connects the lake to the sea dividing the city into southern and northern parts, which are often referred to as the Old Town (Vecliepāja) and the New Town (Jaunliepāja) respectively. The city center is located in the southern part and, although called the Old Town, is relatively more developed. Most of the administrative and cultural buildings are found here as well as the main leisure areas. Along the coast the city extends northwards until it reaches the Karosta Channel (Karostas kanāls). North of the Karosta Channel is an area called Karosta which is now fully integrated into Liepāja and is the northernmost district of the city. Liepāja's coastline consists of an unbroken sandy beach and dunes as does most of Latvia's coastline. The beach of Liepāja is not as exploited as other places (e.g. the Gulf of Riga, Jūrmala and Pärnu in Estonia) but also lacks the tourist infrastructure needed for a fashionable, modern resort.

Jūrmala Park

Jūrmala Park (Seaside Park) is located in the western part of the city at the seaside. The park is 3 km (2 mi) long with a total area of 70 ha and is one of the largest planted parks in Latvia. It was developed at the end of the 19th century. At the end of Peldu Street are Latvia's largest drums – one of the objects of Liepāja's environmental design which reminds one that Liepāja is the music capital of Latvia. The open-air concert stage Pūt, vējiņi! (Blow, wind, blow!) was built in 1964. It has been the venue for a good many concerts and festivals, with the festival "Liepājas Dzintars" ("Amber of Liepāja") being the most famous among them, as it could be regarded as the oldest rock festival of the former Soviet Union. It was held for the first time in 1968. Alongside the stage is an interesting building, the former Bath House built in 1902 and designed by Max Paul Bertschy. At the beginning of the 19th century Liepāja was a renowned health resort and the Russian tsar and his family had been visiting Liepāja. This all encouraged other aristocrats from Russia and Europe to spend their summers in Liepāja as well.

Libava fortress

In the beginning of the 20th century, Libava fortress was the most expensive and ambitious project of the Russian army on the Baltic Sea. The massive concrete fortifications with eight cannon batteries was built to protect the city and its population from German attacks. The fortress' secret underground passages figure heavily in the city's most famous urban legends.

Closest cities

The closest city to Liepāja is Grobiņa, located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away towards Riga. Other main cities in the region are Klaipėda (approx. 110 km (68 mi) to the south), Ventspils (approx. 115 km (71 mi) to the north) and Saldus (approx. 100 km (62 mi) to the east). The distance to Riga (the capital of Latvia) is about 200 km (124 mi) to the east. The nearest point to Liepāja across the Baltic sea is the Swedish island of Gotland approximately 160 km (99 mi) to the north-west. The distance to Stockholm is 216 nautical miles.

Architecture and sightseeing

Liepāja is rich in different architecture styles: wooden houses, Art Nouveau buildings, Soviet-era apartments and a number of green parks all contribute to the character of the city. The main areas of interest for tourists include the city center with its many churches, the Seaside park with white sandy beaches and the northern suburb of Karosta, a former secret military encampment which is now a major tourist attraction. Other areas of interest for tourists are Vecliepāja; Ezerkrasts, which is close to Liepāja lake; and the Karosta beaches with their picturesque blasted forts.

Monuments and memorials

Former monuments

Museums

|

Churches

Notable buildings

|

Transport

The urban transport network of Liepāja relies mainly on buses and minicoaches. As of 2009 there are 12 bus routes and 5 minibus routes in Liepāja. The city also has a single two-way 6.9-kilometre-long (4.3-mile) tram line running through some parts of the city from north-east to south-west, which also provides a vital transport link. The tram line was founded after the opening of the first Liepāja power plant in 1899, which makes it the oldest electric tram line in the Baltic states; it is now operated by the municipal company Liepājas tramvajs. The Port of Liepāja has a wide water area and consists of three main parts. The Winter harbor is located in the Trade channel and serves small local fishing vessels as well as medium cargo ships. Immediately north of the Trade channel is the main area of the port, separated from the open sea by a line of breakwaters. This part of the port can accommodate large ships and ferries. Further north is Karosta harbor, also called Karosta channel, which was formerly a military harbor but is now used for ship repairs and other commercial purposes. Liepāja also welcomes yachts and other leisure vessels which can enter the Trade channel and moor almost in the center of the city. Liepāja has a railway connection to Jelgava and Riga and through them to the rest of Latvia's railway network. There is just one passenger station in the New town, but the railway extends further and links to the port. There is also a northward railway track leading to Ventspils, but in recent decades it has fallen into disuse for economic reasons. The railway provides the main means of delivering cargo to the port. Two main highways, the A9 and A11, connect the city and its port to the rest of the country. The A9 leads north-west towards Riga and central Latvia and the A11 leads south to the border with Lithuania and its only port Klaipėda and to Palanga International Airport. The city also hosts Liepāja International Airport, one of three international airports in Latvia; it is located outside the city limits, north of the Lake of Liepāja near Cimdenieki. The airport is serviced by charter flights and an Air Baltic connection to Riga International Airport.

Communications

Communication systems in Liepāja are well-developed. The city is connected to the global Internet by three optical lines owned by Lattelecom, TeliaSonera International Carrier[29] and Latvenergo and a radio relay line owned by LVRTC. There are four Lattelecom telephone exchanges and the LVRTC TV station and tower, which transmits four national TV channels, two local TV channels — "TV Dzintare" and "TV Kurzeme" and six radio stations. It has two local cable TV operators with a total number of subscribers about 15000 and three local ISPs. The city also has its own amateur radio community[30] and a citywide wireless video monitoring system. As of 2010, digital terrestrial television is fully operational; mobile television and broadband wireless networks are ready for implementation. All four Latvian mobile operators have stable zones of coverage (GSM 900/1800, UMTS, 2100 CDMA450) and client service centers in Liepāja. The city also has fourteen post offices as well as DHL, UPS and DPD depots.

Economy

In the second half of the 20th century under Soviet rule Liepāja became an industrial city and numerous high technology plants were founded, including:

- Mashzavod (Russian: Машзавод, Лиепайский машиностроительный завод)

- Liepajselmash (Russian: Лиепайсельмаш) – 1954 (now Hidrolats)

- Sarkanais Metalurgs (now Liepājas Metalurgs)

- SRZ-29 (Russian: СРЗ-29, 29-й судоремонтный завод) (now Tosmares kuģu būvētava)

- LBORF (Russian: ЛБОРФ, Лиепайская база Океанрыбфлота) – 1964

- Bolshevik (Russian: Рыболовецкий колхоз "Большевик") – 1949 (now Kursa)

- Perambulator factory "Liepāja" (Russian: Колясочная фабрика "Лиепая")

- Mixed fodder plant (Russian: Лиепайский комбикормовый завод)

- Sugar plant (Russian: Лиепайская сахарная фабрика)

- Match factory "Baltija" (Russian: Лиепайская спичечная фабрика "Балтия") – 1957

- Ferro-concrete constructions plant (Russian: Лиепайский 5-й завод железобетонных конструкций) – 1959

- Oil extraction plant (Russian: Mаслоэкстракционный завод)

- SU-426 of BMGS (Russian: СУ-426 треста Балтморгидрострой) (now BMGS)

- Lauma (Russian: Лиепайский галантерейный комбинат Лаума) – 1972

- Linoleum plant

- Shoes factory

After collapse of USSR's centrally planned economy, only some of these plants continue to operate.

Within Latvia Liepāja is well known mostly by coffee brand Liepājas kafija,[31] beer Līvu alus and sugar Liepājas cukurs. In 1997 the Liepaja Special Economic Zone was established for 20 years providing a low tax environment in order to attract foreign investments and facilitate the economic development of Liepāja, but investment growth remained slow due to a shortage of skilled labor force.[32] The main industries in Liepāja are the steel producer Liepājas Metalurgs, building firm UPB and the underwear brand Lauma.[33] The economy of Liepāja relies heavily on its port which accepts a wide range of cargo. The most notable companies working in Liepaja's port are Baltic Transshipment Center, Liepājas Osta LM, Laskana, Astramar and Terrabalt. After joining the European Union in 2004, most of Liepāja companies was faced with strict European rules and terse competition and was forced to stop production or to sell enterprises to European companies. In 2007 Liepājas cukurfabrika and Liepājas sērkociņi closed down; Līvu alus, Liepājas maiznieks and Lauma have been sold to European investors.

Infrastructure

Roads and bridges

- Komunālā pārvalde

Electricity distribution and generation

- Latvenergo

- Vēja parks

Gas

Production

- Liepājas metalurgs

Sewer and water

- Liepājas Ūdens

Heating

- Liepājas Enerģija

Waste management

- Liepājas RAS

Society and culture

Literature, theater and films

Liepāja currently has one cinema, one theater (Liepāja Theatre),[34] one puppet theater, and two regional newspapers ("Kurzemes Vārds" with a circulation of about 10,000 and "Kursas Laiks" with a circulation of about 6,500). The city also has several regional Internet portals. Web forums, blogs, computer games and social networking sites are very popular among young people.

Music

Liepāja is often called the capital of Latvian rock music. Many famous composers and bands have been inspired by Liepāja, including Līvi, Credo, 2xBBM and Tumsa. In the center of Liepāja there was the first Latvian Rock Café (now bankrupt) and the Latvian Musician's Walk of Fame. The oldest pop music festival in Latvia, Liepājas Dzintars was held in Liepāja from 1964 to 2006 presenting bands from Baltic states as well as internationally famous guests. Since 2011 the city has staged the LMT Summer Sound festival, an annual music festival with stages raised directly on the beach. It draws thousands of fans each year. Liepāja also hosts an Organ Music festival and the Piano Stars festival, organized by one of the country's two State Orchestras, the Liepāja Symphony Orchestra.[35] There is also Wind Orchestra Liepāja which was founded by Youth centrum and musical school of Emilis Melngailis. This orchestra also made a new tradition, it made international festival called Wind Rhythms which is widely known in between of eastern European wind orchestras.

Sport

In 1998 an ice hall was built in the city which has since hosted regular ice hockey games including two youth World championship games. HK Liepāja became champions of Latvian Hockey Higher League in 2015–16 season.

In Liepāja is also located Daugava Stadium and Olimpija Stadium – the home stadiums of FK Liepāja and tennis courts.

On 2 August 2008 a new multipurpose sports arena – Liepāja Olympic Centre was officially opened. It has been established as one of the most modern multipurpose sports and cultural complexes in Latvia. 18 000 m2 large area Liepāja Olympic center five floors located in a wide range of functions gyms for basketball, volleyball, floorball, table tennis, boxing, judo, Greco-Roman and free-fighting, as well as space for concerts, conferences, seminars, performances, banquets, contests, dances, meetings and celebrations. Liepāja Olympic center pool and SPA zone is the largest and most modern swimming pool and SPA center in Kurzeme district with a relaxation zone, water massage, bubble baths, three types of saunas, a water attraction zone for children and two swimming pools. Gross floor area of the building is 3200 m2 on three levels: the 1st floor includes entrance hall, reception, cloakroom, beauty salon. On the second floor you will find changing rooms and massage rooms, but the swimming pools and SPA zone are located on the 3rd floor.

Liepāja is home to the BK Liepājas Lauvas, a professional basketball team.[36][37]

The city is also a place of international Rally Kurzeme and a chess tournament Liepājas Rokāde.

Tourism and entertainment

Liepāja encourages tourism. The main attraction is the pristine Blue Flag beach with white sand and rolling dunes, but the city also offers a number of historical sites, including Protestant and Orthodox churches and the ruins of military fortifications from the times of the Russian Empire. A surprisingly well-preserved wooden hut was the residence of Russian tsar Peter the Great for some time while he was touring the region in 1697 during the Grand Embassy.

Nightclubs

- Old Viking

- Big7

- Fontaine Palace

- Red Sun Buffet Beach Club

- Pilsētas vārti

- Mini7

- Loms

- Lācis

Demographics

With 68,945 inhabitants in 2019, Liepāja is the third-largest city in Latvia. Its population has declined since the withdrawal of Soviet military forces; the last of which left in 1994. In addition, many ethnic Russians, emigrated to Russia in 1991–2000. More recent causes include economic migration to western European countries after Latvia joined the EU in 2004, and lower birth rates.

According to the 2011 census, ethnic Latvians make up 55.5% of the population of Liepāja (in comparison, the proportion of native Latvians nationwide is 62.1%). Ethnic Russians make up 30.3% of the population.[38]

|

|

|

Religion

Liepāja has a number of churches. As elsewhere in central and western Latvia, Protestant churches, mostly Lutheran are predominant. Holy Trinity Cathedral houses the seat of the Lutheran Bishop of Liepāja. Other Lutheran congregations are St. Anne, Church of the Cross and Church of Luther. There are four Baptist congregations in the city, among them are St. Paul church and Church of Zion.

Owing to the regional importance of Liepāja during the last decades of the Russian Empire, a number of Russian Orthodox churches were established in the city early in the twentieth century. Their congregations are chiefly drawn from the Russian-speaking population.

The Catholic faith is represented in Liepāja by a St. Joseph Cathedral – seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Liepāja, Catholic primary school and the Catholic centre. The structure of the Catholic centre was used to represent the Vatican in Expo 2000 in Hanover and was transferred to Liepāja after the event.

Other Christian sects include Old Ritualists, Adventist, Pentecostal, Latter-day Saints and Jehovah's Witnesses, who have single congregations and churches.

Government

Fourteen deputies and a mayor make up the Liepāja City Council. City's voters select a new government every four years, in June. The Council selects from its members the Chairman of City Council (also called City Mayor), the two Vice chairmans (Deputy Mayors) which are full-time positions. City Council also appoints the members of four standing committees, which prepare issues to be discussed in the Council meetings: Finance Committee; City Economy and Development Committee; Social Affairs, Health Care, Education and Public Order Committee; Culture and Sports Committee. The City of Liepāja had an operating budget of LVL 31 millions in 2006, more than half of which comes from income tax. Traditionally, political leanings in Liepāja have been right-wing, although only about 70% of the population have voting rights. In recent years the Liepāja Party has dominated the polls. The party has an agreement with the Union of Greens and Farmers, the leading party in the Kučinskis cabinet.

List of city mayors

- Johanns Ruprehts (German: Johann Ruprecht) (about 1631–1638) – the first city burgomaster[43]

Russian Empire

- Kārlis Gotlībs Sigismunds Ūlihs (1878–1880) – the first publicly elected city mayor

- Ādolfs fon Bagehūfilds (1882–1886)

- Hermanis Adolfi (1886–1902)

- Kristiāns Cinks (1902–1906) and (1908–1910)

- Viljams Dreiersdorfs (1906–1908)

- Alberts Volgemuts (1910–1914)

- Teodors Breikšs (1914–1915)

- Andrējs Bērziņš (1918–1919)

Independent Latvia (1918–1940)

Soviet Union (1940–1941)

- Vasilijs Biļevičs (1940–1941)

- Miķelis Būka (1941) First Secretary

Nazi Germany (1941–1945)

- Jānis Blaus (1941–1945)

Soviet Union (1940–1990)

- Matīss Edžiņš (10.05.1945–05.10.1945)

- Rodions Ansons (05.10.1945–21 April 1950)

- Pēteris Ezeriņš (27.12.1950–18 June 1953)

- Voldemārs Lejiņš (1953–1956)

- Jurijs Rubenis (1960–1963) First Secretary

- Ž. Revenieks (1963–1966) First Secretary

- Kārlis Strautiņš (09.11.1965–09.1.1971)

- Jānis Vagris (1967–1973) First Secretary

- Egils Ozols (19.03.1971–29 June 1977)

- Jānis Liepiņš (29.06.1977–07.03.1985)

- Alfrēds Drozda (1985–1990)

Independent Latvia (1990–present)

- Imants Vismins (1990–1994)

- Teodors Eniņš (1994–1997)

- Uldis Sesks (1997–22 November 2018)

- Jānis Vilnītis (22 November 2018–present)[46]

Education and science

Liepāja has wide educational resources. Most well-educated young people leave the city because of low wages and a lack of high-technology and prosperous firms. The city has 21 kindergartens, 8 Latvian language schools, 5 Russian language schools, one school with mixed language of education, 1 evening school, 2 music schools and two boarding schools. Interest education for children and youth is available in 8 municipal institutions: Children and Youth Centre, Youth Centre, Centre for Young Technicians, Art and Creation Centre "Vaduguns", Complex Sport School, Gymnastics School, Tennis Sports School, Sports School "Daugava" (football, track-and-field athletics) and Basketball Sports School.

Higher and professional education in Liepāja represented by:

- University of Liepāja

- Riga Technical University Liepāja branch

- Baltic International Academy Liepāja branch

- Turība University Liepāja branch

- Liepāja Marine College

- Liepaja Medical College

- Liepāja Applied Art School

- Liepāja Carpentry School

- Liepāja Tourism and Textile Design School

Liepāja Central Library has six branches and audio record library. Literature fund consists of about 460,000 copies and online catalog.[47] Average annual number of visitors – 25000.

- Percent of resident population with only primary education (2001) – 14%

- Percent of resident population with secondary education (2001) – 40%

- Percent of resident population with tertiary education (2001) – 9%[48]

Representation in other media

- In 1979 a part of the film Moonzund was filmed in the town.

Notable natives

- Teofils Biķis – Latvian pianist

- Valdemārs Baumanis – basketball coach

- Herberts Cukurs – Latvian aviator and Nazi collaborator

- Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler (1892–1953) – rabbi

- Reuven Dov Dessler (1863–1935) – rabbi

- Ivo Fomins and Tomass Kleins – artists

- Dora Gordine – Estonian-Jewish sculptress

- Morris Halle – Latvian-American Jewish linguist

- Jēkabs Janševskis – writer

- Zvi Harry Hurwitz – South African journalist, Israeli diplomat and adviser to two prime ministers

- Arvids Jansons – Latvian conductor, father of the conductor Mariss Jansons

- Stanisław Jaśkiewicz – Polish actor

- Leon Josephson (1898–1966) – American lawyer and Soviet spy

- Rolf Kahn – football player, father of the German goalkeeper Oliver Kahn

- Mirdza Ķempe – Latvian poet

- Talivaldis Kenins – Canadian composer

- Woldemar Kernig – Russian and German neurologist

- Jacob Klein (1899–1978) – Russian-American Jewish philosopher

- Miroslavs Kodis – journalist, Latvian Television

- Konstantin Konstantinovs – Russian powerlifter

- Vinifreds Kraučis – translator

- John Martens (1875–1936) – architect

- Victor Matison – TV commentator, Rotarian[49]

- Yanka Maur – Belarusian writer

- Zenta Mauriņa (1897–1978) – Latvian writer

- Romans Miloslavskis – swimmer

- Kristaps Porziņģis – basketball player

- Jānis Rinkus – footballer

- Arthur Sakheim (1889–1931) – writer and journalist

- Anastasija Sevastova – tennis player

- Mikhail Sheleg – Russian shanson singer

- Simeon Shubin – physicist

- Lina Stern (1878–1968) – Soviet-Jewish biochemist, physiologist, first female full member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences

- Indriķis Šterns – historian

- Eduards Tisse – Soviet cameraman

- Miķelis Valters – Latvian politician

- Janis Vanags – Latvian Lutheran archbishop

- Māris Verpakovskis – Latvian football striker

- Madars Razma – Latvian professional darts player

- Voldemārs Zandbergs – actor

- Rudolfs Balcers – Forward for the Ottawa Senators

Twin towns – sister cities

Liepāja is twinned with:[50]

Gallery

- Pētertirgus

- St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Naval Cathedral (1901–1903), architect Vasily Kosyakov

Church of St. Anna

Church of St. Anna- Liepāja railway station

The ruins of the northern forts

The ruins of the northern forts St. Joseph church

St. Joseph church.jpg) St. Joseph church (inner view)

St. Joseph church (inner view) Church of St. Anna (altar)

Church of St. Anna (altar)

References

- Murray, 1875, p.85.

- "Liepājas vēsture". liepaja.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Mass murder of Jews in Liepaja (Yad Vashem channel, YouTube)

- "KNAB, the Place Names Database of EKI". Eki.ee. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Turnbull, Stephen, Tannenberg 1410, Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK, 2003, p.82: Certainly Poland & Lithuania invaded Prussia again in 1422, but no mentions of Libau.

- "Лиепая". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Moscow: Советская Энциклопедия. 1969–1978. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Liepaja". Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica.com Inc. 1997.

- "Masonicum". masonicum.lv. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Colomb, Philip Howard. "Memoirs of Admiral the Right Honble. Sir Astley Cooper Key". ebooksread.com. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- Palmer, Alan, Northern Shores, London, 2005, p.215.

- "Liepājas Pastnieks". Latvijas Enciklopēdiskā vārdnīca (in Latvian). Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Либаво-Роменская железная дорога. Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1907. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Paul Max Bertschy". Visit Daugavpils. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Гидроаэродром. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). 1969–1978. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Palmer, 2005, p.255

- Palmer, 2005, p.258.

- Šiliņš, Jānis (18 April 2019). "The republic on the sea: The 1919 coup that exiled the Latvian government to a steamboat". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Hiden, John, and Salmon, Patrick, The Baltic Nations and Europe, Longman Group UK Ltd., 1991, p.32-6.

- Hiden, John, The Baltic States and Weimar Ostpolitik, Cambridge University Press, UK, 1987, p.101-3.

- Hiden & Salmon, 1991, p.78.

- "Crimes of Einsatzgruppen in Liepāja". 1941. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Site of Liepājas slimnica" (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Liepāja Naval Port

- "Liepaja Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Griuzupe, Latvia". Weatherbase. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "Liepaja Climate Normals 1981–2010". Météo Climat. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "Site of the Liepaja museum" (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Site of Karosta prison museum". karostascietums.lv. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Liepāju un Zviedriju savienos optiskais kabelis". Kurzemes Vārds (in Latvian). 23 October 2001. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Site of Liepājas radio amatieru grupa". lrg.lv. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Liepājas kafija". likaffa.lv. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Eglins-Eglitis, Atis; Lusena-Ezera, Inese (2016). "From Industrial City to the Creative City: Development Policy Challenges and Liepaja Case". Procedia Economics and Finance. 39: 122–130. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30256-8.

- "Statistika Latvijas rajonu un to centru griezumā". lursoft.lv (in Latvian). Lursoft. 2005. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Site of Liepājas Teatris". liepajasteatris.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Liepājas simfoniskais orķestris". lso.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "LIEPAJA/TRIOBET basketball team". Eurobasket. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Sākums". www.liepajaslauvas.lv.

- "Pilsonības un migrācijas lietu pārvalde – Kļūda 404" (PDF). www.pmlp.gov.lv.

- Либава. Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). St. Peterburg: Брокгаузъ-Ефронъ. 1907. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Город родной на семи ветрах (in Russian). Liesma. 1976. p. 263. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "PASTĀVĪGO IEDZĪVOTĀJU NACIONĀLAIS SASTĀVS REĢIONOS UN REPUBLIKAS PILSĒTĀS GADA SĀKUMĀ". csb.gov.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Platība, iedzīvotāju blīvums un pastāvīgo iedzīvotāju skaits reģionos, republikas pilsētās un novados gada sākumā. Centrālās statistikas pārvaldes datubāzes. Retrieved 12 June 2017

- "Liepājas pilsētas galvas, birģermeistari". Liepājnieku biogrāfiskā vārdnīca (in Latvian). Letonika. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Ciemojas kādreizējā Liepājas galvas Lapas mazmeita". Kurzemes vārds (in Latvian). 17 September 1999. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Pirms 130 gadiem dzimis Liepājas mērs Leo Lapa". irLiepāja (in Latvian). 21 September 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Ozola, Inga (22 November 2018). "Long-standing Liepāja mayor steps down". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Catalog of Liepaja central library". liepajasczb.lv (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Liepaja profile". Urban Audit. 2001. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "CV of Victor Matison". Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Sadraudzības pilsētas". liepaja.lv (in Latvian). Liepāja. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

Bibliography

- Мелконов, Юрий (2005). Пушки Курляндского Берега. Riga, LV: GVARDS. ISBN 9984-19-772-7.

- Кондратенко, Р. В. (1997). "Военный порт Александра III в Лиепае". Saint-Peterburg, RU: Исторический альманах "Цитадель", №2(5), изд. "ОСТРОВ". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Вушкан, Янис Владиславович (1976). "Город родной на семи ветрах". Riga, LV: Liesma. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tooms, Viljars (2003–2007). "Liepājnieku biogrāfiskā vārdnīca". Riga, LV: Tilde Letonika. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sāne (Alksne), Līga (1991). "Ceļvedis Liepājas arhitektūrā". Liepāja, LV: Liepājas pilsētas TDP IK Arhitektūras un pilsētbūvniecības pārvalde. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jāņa sēta. (2003). Liepājas pilsētas plāns. Riga, LV: Karšu izdevniecība Jāņa sēta. ISBN 9984-07-330-0.

- Gintners, Jānis (2004). "Liepājas gadsimti". Liepāja, LV: Liepājas muzejs. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gintners, Jānis, Uļa (2008). Liepāja Latvijas sākotnē. Liepāja, LV: Liepājas muzejs. ISBN 978-9984-39-723-8.

- Gintnere, Uļa (2005). Liepāja laikmetu dzirnavās. Liepāja, LV: Kurzemes Vārds. ISBN 9984-9190-4-8.

- Lancmanis, Imants (1983). "Liepāja no baroka līdz klasicismam". Rīga, LV. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Liepājas 300 gadu jubilejas piemiņai: 1625–1925". Liepāja, LV. 1925. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wegner, Alexander (1970) [1878]. Geschichte der Stadt Libau. Libau: v. Hirschheydt. ISBN 3-7777-0870-4.

- Tīre, Irina (2007). Liepāja in graphics. Latvia: Poligrāfijas infocentrs. ISBN 978-9984-764-92-4.

- Dorenskis, Jaroslavs (2007). "Liepājas Metalurgs: Anno 1882". Liepāja, LV: Fotoimidžs: 364. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Корклыш, С. (1966). Лиепая (in Russian). Rīga: Liesma. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Evans, Nicholas J. (2006). "The Port Jews of Libau, 1880–1914". In David Cesarani; Gemma Romain (eds.). Jews and Port Cities: 1590–1990: Commerce, Community and Cosmopolitanism. London, UK: Vallentine Mitchell & Co Ltd. pp. 197–214. ISBN 978-0-85303-681-4.

- Eberstein, Ivan H. The Amber Land: Libava's Tragic Fate and the Fall of the Russian Empire. New York.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Liepaja. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liepāja. |

- www.liepaja.lv – Liepāja City Council official website

- History of Liepāja

- www.liepajniekiem.lv – Liepāja news in Latvian and Russian (in Latvian and Russian)

- www.portofliepaja.lv – Port of Liepaja

- www.orkestris-liepaja.lv – Liepaja Symphony orchestra

- Kurzemes Vārds – Liepāja regional newspaper (in Latvian)

- Kursas Laiks – Liepāja district newspaper (in Latvian)

- Rožu laukums – Webcam showing "Rose square" in Liepaja

- Libavas Nami – Real estate agency in Liepaja

- Autoserviss 4U – Car service in Liepaja

- The murder of the Jews of Liepāja during World War II, at Yad Vashem website

- Liepāja, Latvia at JewishGen

- Liepaja Info – Mobile Application