Kyaukmyaung (Sagaing)

Kyaukmyaung is a town in Sagaing Division, Myanmar. It is situated 46 miles north of Mandalay on the west bank of the River Irrawaddy, and 17 miles east of Shwebo by road.[1][2] It marks the end of the third defile of the Irrawaddy.[3]

Kyaukmyaung | |

|---|---|

Town | |

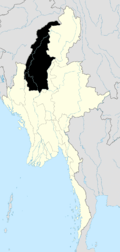

Kyaukmyaung Location in Burma | |

| Coordinates: 22°35′0″N 95°57′0″E | |

| Country | |

| Division | |

| Population (2015) | 15,000 |

| • Religions | Buddhism |

| Time zone | UTC+6.30 (MST) |

Kyaukmyaung is a pottery village where the majority of the 15,000 residents who live there participate in the San Oh, or pottery, industry in some way. Kyaukmyaung is home to the only four large scale glaze factories in upper Myanmar. The largest is Nweyein.[4]

History

Ceramic traditions in this area were first started in the Ma-u and Ohn Bin villages in the 18th century when 5,000 Mon war captives were settled in the area by King Alaungpaya (1752–1760) after his conquest of Pegu.[5] Earlier, the Peguans from the south had rebelled and deposed the King of Ava. Aung Zeya (later Alaungpaya), chief of Moksobo (later Shwebo), led his countrymen in a revolt against the Mon, and collected a fleet at Kyaukmyaung where he defeated the advancing Mon.[6]

Second World War

When the Japanese invaded Burma in 1942, the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company was ordered to scuttle their rivercraft at both Mandalay and Kyaukmyaung by the retreating British colonial government.[7] The river, about half a mile wide at this point, was crossed and bridgeheads established in January 1944 by the 19th Infantry Division (India) at both Kyaukmyaung and Thabeikkyin, when the Allied forces counter-attacked.[8][9] In 1960 the village decided to relocate to their current location from Ohn Bin and Ma-u to Kyaukmyaung, which is approximately 6 miles away, because of a natural deposit of clay located at Kyaukmyaung.

Pottery and ceramics

Kyaukmyaung is famous for the manufacture of large glazed earthenware pots sometimes known as Kyaukmyaung pots. The majority of this village's economy stems from sending floating these pots downstream. Kyaukmyaung pots are thrown with 40 pounds of clay, and can hold 150 Vis (200 liters) of liquid.

Kyaukmyaung is home to four large scale pottery "villages" or complexes - Nwenyein, Shwegon, Shwedaik, and Malar. Nwenyein is the largest of the four and employs 52% of the population. Nwynyien employs people to do everything from harvesting the clay from the riverbed to bringing in firewood for the firing process.[4] The factory is located about 0.75 kilometers away from the bank of the stream. The complex has four very large wood kilns, two mixing stations that grind dry clay and two rooms for throwing (one for the very large San Oh pots, and the other for the smaller everyday use objects). There are two rooms for glazing, and three to five rooms for greenware.

Clay body

Two kinds of clay are used, sourced from two specific places. One clay comes from the Irrawaddy riverbed, and is a red based earthenware clay that has a high copper content. The second is a yellow clay, which is cosmic and lime based, found at a deposit 2 kilometers away. The two types of clay are mixed together with ground dried clay bricks and then refined. After this process is complete the clay may be stored for up to two years, but is also ready to be used right away.

Throwing

The throwing is done in two separate rooms, depending on the type of pot that is being made. Kyaukmyaung pots are thrown on a human operated wheel submerged in the ground. Throwing these very large pots often requires two or three men. One man keeps the wheel in motion by spinning it with his hands, and the other two work on throwing. This is a very laborious process because of the sheer size of these pots. A single pot is thrown with about 40 pounds of clay. Pots are thrown in two pieces and later combined. Clay is distributed to the wheel in a stretched out logs when the wheel is in motion. This varies from the traditionally western style of throwing, where the entirety of the clay being used for the section is placed on the wheel and centered afterward. This centering process is designed so that the height of these pots is dramatically increased. It also helps to reduce air bubbles from interfering with the throwing process. The bottom section of the pot is thrown first.

After a pot has been thrown it is left to dry to the leather-hard phase on the wheel. To prevent distortion in the drying process, throwers will often tie twine made from straw around the pot so it retains its circular shape. This is especially important to the stacking process.

The ceramicists then throw the top portion of the pot, which they throw upside down. They measure the needed circumference with twine made from straw. When the pot is finished they remove it with string, let it dry to leather hard, and then attach it to the bottom portion of the pot. They do so through the scratch and slip method, in which they rough up the edges of the two separate pieces of the pot that they would like to stick together. Then the ceramicists apply a finer more watered down version of the clay to the scratched area and fuse them together on the wheel where the bottom part of the pot has been drying. After this is complete, they use the wheel and clean up the extra slip and visible evidence of the fusion, and confirm that the pot is fully centered. After a little more drying, they remove the pot from the wheel and place it outside to dry. The pots are still bound in string so that they retain their shape. This drying process normally takes two full days in the dry season. After two days these pots are bone dry and ready to be fired.

Only men throw the Kyaukmyaung pots because they are so big that they require longer arms to reach the bottom, and that requires significant strength.

The more decorative and smaller types of pottery are thrown by women. They are generally thrown off the hump or a large block of clay that is centered and then used to throw three or four ceramic objects. Smaller bowls are made for plants or decorative water jars. These wheels are also man powered wheels and are spun by one woman kicking the wheel at a constant pace, and generally one woman operates this while the other does the throwing.

Glazes

Traditionally the glazes that are used are mostly slipware or glazes formed from the purest and smallest particles found in the clay body. Two main glazes are applied to the pots. The first of these is a yellow glaze that is formed by adding chalk to the natural clay body. The glaze is an off-white before the firing and after turns into a warm yellow. The second glaze is made similarly, but instead of adding chalk, the villagers use burned batteries, and some compound in the batter ash turns the glaze black when fired.

In 1973 the glaze process started changing to meet more global standards. The most aggressive change was the use of glass powder based glazes instead of slip glazes. The glass powder is still sometimes mixed with the chalk and battery plate powder, but is often mixed with lead carbonate ore, carbon oxide and cobalt oxide to achieve many of the traditional glazes. In the 1990s Nwenyein started using various paints under the glass powder glaze for some of the decorative pottery.

Firing processes

Kyaungmyauk has four functional wood kilns. They are very large and insulated by bricks. They are overseen by the firing master, one of the most senior positions at the compound.

When thrown and let dry to a bone dry stage, the pots are loaded into a massive kiln. The kilns can hold up to 80 large pots and around 20 smaller pots that are often fired inside of the larger pots. They prevent the pots from sticking together by using ash.

When the pots are loaded into the kiln, wood gatherers bring in wood by the truckload for this firing. The wood comes from as far away as 60 kilometers, and is generally harder wood. The firing process differs from western firing because the fire master does not know the specific temperatures that they fire pots to. Instead, they measure how long to fire these pots for based on how many truckloads of wood they have to use and the duration. Although every wood kiln firing is different, they tend to fire for two days and use four truckloads of wood.

Economic importance

Since the 1990s, the large domestic demand for glaze wear has dramatically decreased. This is largely due to the fact that these pots last a very long time. This factor, along with the high cost of production, has caused most of the small scale factories to go out of business. Leaving behind the four factories that make up Kyaungmyauk pottery village, each of these factories follow a similar structure of being led by a single entrepreneur who oversees all of the production and coordination with wholesale vendors and stores in Yangon and father down the river. The wages vary based upon the level of skill of the workers, but skilled positions such as throwers are paid four U.S. dollars a day and wood gatherers $3 a day. All workers are allowed to take out a $500 loan from the owner every year to help them with their finances.

The Kyaukmyaung pots are sold for $18–$20 directly from the factory. The majority of the pots are floated downstream on giant boats. The pots in Yangon are often sold for anywhere between $40 and $50 US. The pots are sold to different retailers in Yangon and along the Irrawaddy river. They are very popular in Myanmar as they have many uses.

However, the market saw a significant decrease after 1990, because urban demand for glazed pottery decreased. In 2008 and 2009 the market saw a large boom in the wake of Cyclone Nargis.The cyclone destroyed many of the existing water storage systems, and UNICEF focused on water sources and hygiene as a response strategy.[10] As part of this, UNICEF contracted Kyaukmyaung to make the traditional pots to serve as temporary solutions to a lack of fresh water. This triggered a revival of the economy, as an increased demand allowed Kyaumyaung to sell the pots for more profit.

Uses

Kyaukmyaung pots are traditionally used for storing and fermenting food and drink items. The most common use is the fermentation of liquor. Other uses include storing and fermenting fish paste and chili paste. The smaller bowls are often used to store drinking water, grain, and rice.[4]

Tourism

Kyaukmyaung is gathering fame as a tourist destination. More tour groups are stopping here as part of cruise ships on the Irrawaddy river cruises often stop here on their tours from Bagan to Mandalay. This has brought the town much tourism from Europe and America, and led to a creation of a shop where tourists can buy the ceramics.[11]

Irrawaddy dolphins

A 2004 survey of the Irrawaddy dolphin counted 18 to 20 between Kyaukmyaung and Mingun. In December 2005 the Department of Fisheries designated the 72 km stretch of the Irrawaddy between these two points a protected area for the dolphins.[12][13][14]

References

- Alan Jeffreys, Duncan Anderson. The British Army in the Far East 1941–45. Osprey Publishing, 2005. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- "Highlights of Myanmar: Kyaukmyaung". Journeysmyanmar.com 28 May 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- "Irrawaddy River". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- Than, Yee Yee. "Product Innovation Under Different Market Environment: A Case Study of Kyaukmyaung Area, Shwebo Township." Universities Research Journal: 289.

- Dr Sein Tu. "Myanmar's long and documented history of making big glazed jars". Myanmar Times 6, 110–111. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- Michael Symes (1800). An Account of an Embassy to the Kingdom of Ava, sent by the Governor-General of India, in the year 1795 (PDF). SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research VOL. 4, Issue 1 Spring 2006. p. 64. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- "The Irrawaddy Flotilla Company". Pandaw1947,com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- Mukund Murty. "Encounters with WW2 RIAF Veteran: Air Cmde Nanu Shitoley DFC". Indian Air Force (Bharatiya Vayu Sena). Archived from the original on 2009-02-01. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- Artie Gilbert. "WW2 People's War: The Crossing of the Irrawaddy". BBC. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/myanmar_43788.html

- http://www.irrawaddyprincess2.com/

- Shingo Onishi. "Mutualistic Fishing Between Fishermen and Irrawaddy Dolphins in Myanmar" (PDF). TIGERPAPER FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Vol. 35: No. 2 Apr–Jun 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- "Role of Wildlife Conservation Society in Myanmar" (PDF). Wildlife Conservation Society. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-04-01. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- Sann Oo. "Lost dolphin returned to river". Myanmar Times Volume 21, No. 402, January 21–27, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-03-31. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

External links

- A potter at Nwe Nyein

- Glazed Ceramics in Myanmar, The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies, Vol. 23 (20051227), pp. 55–80

.svg.png)