Konzhukovia

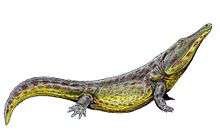

Konzhukovia is an amphibian genus that belongs to an extinct group of temnospondyls, the largest clade of basal tetrapods including about 198 genera, 292 species, and more than half of which were alive during the early Mesozoic period.[1] The animal was a predator that lived about 260 million years ago, and could get up to about 3 meters in length.[2] Specifically, Konzukovia lived during the Permian, between 252 and 270 million years ago according to the type of rock the fossil was found in.[2] There are three species within this genus, K. vetusta, K. tarda, and K. sangabrielensis, the first two originating from Russia while the latest originating from Southern Brazil.[2] The discovery of this specimen in Southern Brazil provided more evidence to support the idea that during this animals existence, there was a “biological corridor” because of the supercontinent Pangea, allowing these species to be found so far apart from each other. Konzhukovia belongs to the family Archegosauridae, a family consisted of large temnospondyls that most likely compare to modern day crocodiles. Since the discovery of the latest species, K. sangabrielensis Pacheco proposes that there must be the creation of a new family, Konzhokoviidae, a monophyletic group in a sister-group relationship with Stereospondlyi in order to accommodate the three species.[2] Konzhukovia skulls usually exhibit typical rhinesuchid features including an overall parabolic shape, small orbits located more posteriorly, and the pterygoids do not reach the vomer.[3] These animals were long-snouted amphibians that had clear adaptations made for fish catching,[3] as well as exemplifying aquatic features.[4]

| Konzhukovia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Konzhukovia Gubin, 1991 |

| Species | |

| |

Etymology

The name Konzhukovia, was given because of its “rhinesuchid-like” temnospondyl properties.[3] It was assigned the name Konzohuvia by Schoch and Milner.[5] The specific name sangabrielensis (a species type) is derived from the municipality where the specimen was recovered in southern Brazil.[2]

Paleobiology

The Konzhukovia skull has an overall triangular appearance due to the lateral margins of the snout expanding parallel and then diverging from each other and the most anterior portion of the snout is rounded.[2] The skull contains both infra- and supraorbital sensory sulci, the infraorbital sulcus is located on the maxilla and runs posteriorly to the lacrimal while the supraorbital sulcus extends posteriorly to the naris.[2] The orbits are elongate and the skull shows paired anterior palatal vacuity.[6] The orbits are positioned after the midline of the skull and are relatively widely separated from each other.[7] The skull contains pleurodont dentition and the maxilla and premaxilla of recovered specimens carry evidence of more than 30 teeth.[2] The tooth row runs straight between the vomerine fangs, the vomerine tusks and palatine tusks are equal in size, and the maxillary teeth are anteroposteriorly compressed.[2] Comparing the three species, K. sangabrielensis was almost twice the size of both K. tarda and K. vetusta and appeared to be very robust in overall shape.[2] Pacheco used phylogenetic inference to infer that K. sangabrielensis was missing the septomaxilla due to fact that the absence of this bone is a common feature in its relatives, as it was not visible in the specimen found representing K. sangabrielensis.[2] All three Konzhukovia species exhibit oval nostrils with wide lateral openings located on the anterior edge of the snout (Pacheco, 2016). The premaxilla, maxilla, and nasal all make contact with the nostrils edges and the prefrontal is fragmented.[2] The maxilla is what forms most of the lateral portion of the choanae, giving an overall long and oval form which is seen in all konzhukoviids and several other temnospondyls.[2] The vomer contacts the maxilla and its lateral process reaches the same level as the palatine tucks.[2] The cultriform process of the parasphenoid in K. vetusta and K. tarda is inserted between the vomers.[2] These animals have interpterygoid vacuities which appear to be oval and elongated, the palatine is what forms the most anterior part of the vacuity.[2] The pterygoids are fragmented and in K. tarda, the palatine ramus of the pterygoid runs anteriorly to the palatine tusks, unlike in K. vetusta where the palatine ramus ends at the same level.[8] The illiac blade is known to be not bifurcated in K. vetusta.[9]

Discovery

Konzhukovia vetusta

Konzhukovia vetusta was discovered in 1955 by E. D. Konzhukova. A K. vetusta skull was found in the Bolshekinelskaya Formation at the Malyi Uran locality, Orenburg region, in Russia.[10] The K. vetusta skull was originally described by Gubin, in 1991, and assigned to the family of Melosauridae which later becomes renamed.[10]

Konzhukovia tarda

Konzhukovia tarda was found in the Ocher Assemblage Zone in the Orenburg region of Russia.[10]

Konzhukovia sangabrielensis

In 2016, Cristian Pereira Pacheco described K. sangabrielensis from the anterior half and partial right side of a skull roof and palate of a temnospondyl from South America. After diagnosis of the species by Pacheco and his group, it was clear that it was of the genus Konzhukovia which was previously recorded exclusively from Russia. The specimen of K. sangabrielensis that is described by Pachecho was recovered from Posto Queimado (Early Guadalupian), Rio do Rasto Formation, state of Rio Grande do Sul, southern Bazil.[2] Initially, this specimen was recorded as a Melosaurinae by Dias-da-Silva (2012), but phylogenetic analysis supported its placement within Tryphosuchinae, basal to the Russian temnospondyls of this group.[2] Once K. sangabrielensis was discovered, the new family of Konzhokoviidae was proposed in order to accommodate the new Brazilian species in relation to its Russian relatives.[2] K. sangabrielensis remains the basal most konzhukoviid in the family.[2]

Geological setting

The Rio do Rasto Formation, where K. sangabrielensis was recovered, ranges from Guadalupian to Lopingian.[11] The Permian specimens that have been found in southern South America only consist of fossil faunas in the Rio do Rasto Formation.[2]

The Southern Urals area of European Russia, where K. tarda and K. vetusta were found, have been the recovery site of many amphibians and reptiles from the Upper Permian, dating back to the 1940s.[10] The area with rich deposits consists of 900,000 km2 of land between River Volga in the northwest and Orenburg in the southwest.[10] A continental succession consisting of mudstones, siltstones, and sandstones provides specimens from the last two stages of the Permian, the Kazanian and Tatarian.[10]

References

- Schoch, Rainer R. (August 2013). "The evolution of major temnospondyl clades: an inclusive phylogenetic analysis". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (6): 673–705. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.699006.

- Pacheco, Cristian Pereira; Eltink, Estevan; Müller, Rodrigo Temp; Dias-da-Silva, Sérgio (2016). "A new Permian temnospondyl with Russian affinities from South America, the new family Konzhukoviidae, and the phylogenetic status of Archegosauroidea". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 15 (3): 241–256. doi:10.1080/14772019.2016.1164763.

- Barberena, M.C. (1998). "On the precense of a shortsnouted Rhinesuchoid amphibian in the Rio do Rastro Formation (Late Permian of Parana Basin, Brazil)". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências.

- Yates, A.M.; Warren, A.A. (2000). "The phylogeny of the 'higher' temnospondyls (Vertebrata: Choanata) and its implications for the monophyly and origins of the Stereospondyli". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 128 (1): 77–121. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00650.x.

- Schoch, Rainer; Milner, A.R. (2000). Stereospondyli. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie. 3B. p. 203.

- Shishkin, Mikhail (2000). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–59.

- Gubin, Y.M. (January 1997). "Skull morphology of Archegosaurus decheni Goldfuss (Amphibia, Temnospondyli) from the Early Permian of Germany". Alcheringa. 21 (2): 103–121. doi:10.1080/03115519708619178.

- Gubin, Y.M. (1991). "Permian archegosauroid amphibians of the USSR". Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta, Akademiya Nauk.

- Eltink, Estevan; Langer, Max C. (2014). "A new specimen of the temnospondyl Australerpeton cosgriffi from the late Permian of Brazil (Rio do Rasto Formation, Paraná Basin): comparative anatomy and phylogenetic relationships". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (3): 524–538. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.826667.

- Tverdokhlebov (2005). "Upper Permian vertebrates and their sedimentological context in the South Urals, Russia". Earth-Science Reviews. 69 (1–2): 27–77. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.07.003.

- Holz, Michael; França, Almério B.; Souza, Paulo A.; Iannuzzi, Roberto; Rohn, Rosemarie (March 2010). "A stratigraphic chart of the Late Carboniferous/Permian succession of the eastern border of the Paraná Basin, Brazil, South America". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 29 (2): 381–399. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2009.04.004.