Ribbon of Saint George

The ribbon of Saint George (also known as Saint George's ribbon, the Georgian ribbon; Russian: георгиевская ленточка, georgiyevskaya lentochka, and the Guards ribbon in Soviet context: see Terminology for further information) is a Russian military symbol consisting of a black and orange bicolour pattern, with three black and two orange stripes. It appears as a component of many high military decorations awarded by the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the current Russian Federation.

| Ribbon of Saint George Георгиевская лента | |

|---|---|

| Versions | |

Flag of the Saint George Ribbon. | |

.svg.png) The Ribbon of Saint George (tied). The pattern is thought to symbolise fire and gunpowder. It is also thought to be derived from the colours of the original Russian imperial coat of arms (black eagle on a golden background). | |

| Adopted | Order of Saint George, established in 1769 |

In the early 21st century, the ribbon of Saint George has come to be used as an awareness ribbon for commemorating the veterans of the Eastern Front of the Second World War (known in post-Soviet countries as the Great Patriotic War). It enjoys wide popularity in Russia as a patriotic symbol, as well as a way to show public support to the Russian government, particularly since 2014.[1] However, it is much more controversial in other post-Soviet countries, such as Ukraine and the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), due to its association with Russophilia and Russian irredentism.[2]

Terminology

As the ribbon of Saint George has been used by different Russian governments, multiple terms exist for it in the Russian language. The ribbon first received a formal name in the Russian Empire, in documents prescribing its usage as an award: the Georgian ribbon (Russian: георгиевская лента, georgiyevskaya lenta). The old Tsarist term was used in the Soviet Union to describe the black-orange ribbon in the Soviet award system, but only in non-official contexts, such as the Military History Journal published by the Soviet Ministry of Defense. Formally, the black-orange ribbon on the badges, flags and cap tallies of Guards units was called the Guards ribbon (Russian: гвардейская лента, gvardeyskaya lenta),[3][4] while the same ribbon as it was used in other Soviet awards had no official name. In the military terminology of the Russian Federation, both Tsarist and Soviet terms are used.[5][6]

The modern term георгиевская ленточка (georgiyevskaya lentochka, distinguished from the Tsarist term by the usage of the diminutive) comes from the Russian 2005 program of the same name, and is used to refer to the mass-produced awareness ribbons as opposed to the original military awards. The usage of the epithet Georgian in reference to that ribbon is subject to controversy in Russia, due to its Tsarist connotations, and thus sometimes the term Guards ribbon is used to refer to the modern ribbons as well, as they are meant to commemorate the Soviet period of Russian history.[7]

Its resemblance to the black-and-orange-striped invasive, destructive Colorado potato beetle has gained the ribbon the derogatory nickname "Colorado ribbon" (Russian: колорадская лента, koloradskaya lenta; Ukrainian: колорадська стрічка, kolorads'ka strichka) in Russia and Ukraine.[8][9][10] The ribbon is associated by some people with the Russian military and Russian irredentism in general, and was used as a recognition symbol by "local self-defence forces" in the occupation of Crimea and pro-Russian separatist forces in the Donbass War.[11] Over time the term kolorad ("Colorado") in Russian and Ukrainian has become a pejorative applied to extreme Russian patriots, pro-Russian separatists, and invading Russian militants.[12][13] Incidents over the Ribbon happen quite often during the May 8-9 Victory in Europe Day Victory Day (9 May) celebrations.[14]

History

Origins

.jpg)

The Georgian ribbon emerged as part of the Order of Saint George, established in 1769 as the highest military decoration of Imperial Russia (and re-established in 1998 by Presidential decree signed by then President of Russia Boris Yeltsin). While the Order of Saint George was normally not a collective award, the ribbon was sometimes granted to regiments and units that performed brilliantly during wartime and constituted an integral part of some collective battle honours (such as banners and pennants). When not awarded the full Order, some distinguished officers were granted ceremonial swords, adorned with the Georgian ribbon.[15]

In 1806, distinctive Georgian banners were introduced as a further battle honour awarded to meritorious Guards and Leib Guard regiments. These banners had the Cross of Saint George as their finials and were adorned with 4,44 cm wide Georgian ribbons. It remained the highest collective military award in the Imperial Russian Army until the Revolution in 1917.

In the original statute of the Order of Saint George, written in 1769, the currently orange stripes of the ribbon were described as yellow; however, they were frequently rendered as orange in practice,[7] and the orange colour was later formalised in the 1913 statute.[16] The colours are said to symbolise fire and gunpowder of war, the death and resurrection of Saint George, or the colours of the original Russian imperial coat of arms (black double-headed eagle on a golden escutcheon).[17] Another theory is that they are, in fact, German in origin, derived from the or and sable stripe patterns found on the heraldry of the House of Ascania, from which Catherine II originated, or the County of Ballenstedt, the house's ancient demesne.[18]

The original Georgian ribbons disappeared alongside all other Tsarist awards after the October Revolution, although wearing a previously earned Cross of Saint George was allowed. However, the symbol would reappear during the Second World War, as a symbol of office for the newly established Guards units, whose badges and banners were adorned with black and orange ribbons in a similar manner to old Imperial regiments[17] Later, the same ribbon would be used for the Order of Glory (Russian: Орден Славы, Orden Slavy), an award given for bravery to soldiers and non-commissioned officers similar to the Tsarist Cross of Saint George, and the medal "For the Victory over Germany" (Russian: За победу над Германией, Za pobedu nad Germaniyey), awarded to almost all veterans who participated in Eastern Front campaigns. As part of the original Tsarist awards, the ribbon was also used by the collaborationist Russian Liberation Army.[19]

After the war, the ribbon would be sometimes used in postcards commemorating the veterans of the war;[20] however, the ribbon did not hold the public significance it has today.[19]

Russian Federation

In 2005, to mark the 60th anniversary of Victory Day (9 May 1945), the news agency RIA Novosti and the youth civic organization РООСПМ «Студенческая Община» launched a campaign that called on volunteers to distribute ribbons in the streets ahead of Victory Day.[19][15] Since then, civilians in Russia and other former republics of the Soviet Union have worn the ribbon as an act of commemoration and remembrance.[15] For the naming of the ribbons the diminutive form is used: георгиевская ленточка (georgiyevskaya lentochka, "small George ribbon").[15] Since 2005 the ribbon is distributed each year all over Russia and around the world in advance of 9 May and is on that day widely to be seen on wrists, lapels, and cars.[21][15] The public campaign is associated with other symbols, such as the motto: "We remember, we are proud!" (Russian: Мы помним, мы гордимся!)[15]

Yulia Latynina and other journalists have speculated the Russian government introduced the ribbon as a public-relations response to the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine in which demonstrators had adopted orange ribbons as their symbol.[19][21]

Subsequently, Russian nationalist and government loyalist groups have adopted the ribbon. During the 2011–13 Russian protests, protestors demonstrating against electoral fraud in the 2011 elections wore white ribbons. Supporters of Putin would counter-protest wearing Saint George's ribbons.[22] On 28 April 2016 a group of people from the National Freedom Movement[23] wearing St. George ribbons attacked a school competition organized by the Memorial society, pouring a toxic solution of Brilliant Green on writer Ludmila Ulitskaya and other guests and assaulting a journalist.[24][25] The Russian ultranationalist group National Liberation Movement (Russian: Национально-освободительное движение - NOD) has adopted a flag of orange and black horizontal stripes as its symbol.[26]

During the events of 2014 in Ukraine, Antimaidan activists and the pro-Russian population of Ukraine (especially in the south-east regions) used the ribbon as a symbol of pro-Russian and separatist sentiment.[27][8][28][29] Pro-Russian paramilitary groups, such as the Donbass People's Militia paramilitary group, use Saint George ribbons in their uniforms and emblems.

Controversies

Lately, the yellow-black ribbon was adopted as a “friend or foe” marking of terrorist groups outside Russia.

Ukraine

In April 2014 the veterans of Kirovohrad banned the symbol from Victory Day celebrations "in order to prevent provocations between the activists of different movements". Instead, only Ukrainian state symbols would be used.[30] The next month Cherkasy urged veterans and supporters not to wear the ribbon or any other party symbols.[31]

The Ukrainian government replaced the ribbon with a red-and-black remembrance poppy, like those associated with Remembrance Day in Western Europe in 2014.[19][32]

On May 16, 2017 the St. George Ribbon was officially banned in the country, with those who produce or promote the symbol subject to fine or temporary arrest. According to Speaker Andriy Parubiy, the symbol had become a symbol of "Russia's war and occupation of Ukraine."[33]

Belarus

On 5 May 2014, the Belarusian Republican Youth Union encouraged activists not to use the ribbon. Other officials reported that the decision not to use the symbol was related to the situation in Ukraine, "where the ribbon is used by militants and terrorists".[34] In time for Victory Day 2015, the ribbon's colors were replaced by the red, green and white from the Flag of Belarus.[35] But the President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko arrived on 7 May 2015 in Moscow with a Saint George ribbon combined with the flag of Belarus placed on the lapel of his jacket, thus showing his personal positive attitude to the ribbon.

Canada

During preparation for the first Victory Day parade in the Canadian city of Winnipeg on 10 May 2014, the Russian embassy distributed Ribbons of Saint George to participants. The move was considered controversial in view of the ongoing events in Ukraine with the Ukrainian Canadian Congress calling the ribbon a "symbol of terrorism."[36]

Kazakhstan

Some parties made statements intended to discourage the use of the ribbon in Kazakhstan in 2014 for Victory Day celebrations, suggesting that red (of the Red Army) and turquoise (the national color of Kazakhstan) should be used instead.[37] However, no official authority issued any comments.

Latvia

The government of Latvia proposed the ban on the use of any Ribbons of Saint George by law in May 2014; earlier, Latvia imposed a ban on the use of all Soviet symbols at public events.[38]

Lithuania

The ban on similar grounds to that in Latvia has been discussed.[39]

Gallery

Saint George Standard of the Life Guard Cuirassier Regiment 1817

Saint George Standard of the Life Guard Cuirassier Regiment 1817 Beret badge with ribbon of St George of a Russian Federation Guards unit

Beret badge with ribbon of St George of a Russian Federation Guards unit Ribbon of Saint George on a car antenna, Moscow, May 2008

Ribbon of Saint George on a car antenna, Moscow, May 2008 Victory Day 2014 in Donetsk, Ukraine, people with Saint George ribbons

Victory Day 2014 in Donetsk, Ukraine, people with Saint George ribbons Pro-Russian separatist Vostok Battalion member wearing a Saint George ribbon armband

Pro-Russian separatist Vostok Battalion member wearing a Saint George ribbon armband Mikhail Kutuzov with Saint George Ribbon, c. 1777

Mikhail Kutuzov with Saint George Ribbon, c. 1777 Ivan Gannibal with Saint George Ribbon

Ivan Gannibal with Saint George Ribbon Nicholas II of Russia with Saint George Ribbon

Nicholas II of Russia with Saint George Ribbon Shoulder sleeve insignia of the Ukrainian Army 169th Training Center

Shoulder sleeve insignia of the Ukrainian Army 169th Training Center Shoulder sleeve insignia of the 300th Mechanized Regiment (Ukraine)

Shoulder sleeve insignia of the 300th Mechanized Regiment (Ukraine) Insignia of the 25th Airborne Brigade (Ukraine)

Insignia of the 25th Airborne Brigade (Ukraine)

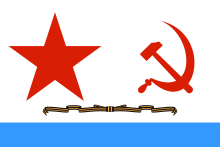

Flags

On July 21, 1992, by the Decree of the President of Russia under Boris Yeltsin, the need for new naval banners for the Russian Federation was created under decree № 798.[40] Article 1, section 2 states the description of the "Guards naval flag" with the "Guards Ribbon" located in the middle of the lower half of the flag, symmetrically relative to the middle vertical line of the flag. The usage of the Soviet term "Guards Ribbon" in modern Russian laws were only in reference of the Guards units of the Soviet Navy. These units were subsequently acquired by the newly formed Russian Navy after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Flag of the Saint George Ribbon

Flag of the Saint George Ribbon 1942-1950 Soviet Guards naval flag

1942-1950 Soviet Guards naval flag 1950-1992 Soviet Guards naval flag

1950-1992 Soviet Guards naval flag First Guards naval flag of the Russian Navy, 1992-2000

First Guards naval flag of the Russian Navy, 1992-2000 Second version of the Guards naval flag, reverted to the historical color of the original St Andrews's flag, 2000

Second version of the Guards naval flag, reverted to the historical color of the original St Andrews's flag, 2000- Pro-Russian demonstration in Odessa in 2014

- 1942-1950 Guards Naval Flag

Russian Naval flag with the Order of Nakhimov and the Guards Ribbon on the Battle Cruiser Moskva

Russian Naval flag with the Order of Nakhimov and the Guards Ribbon on the Battle Cruiser Moskva

Medals

Russian Federation Order of Saint George 4th class

Russian Federation Order of Saint George 4th class Imperial Cross of Saint George 3rd class 1807 - 1917 (enlisted award)

Imperial Cross of Saint George 3rd class 1807 - 1917 (enlisted award) Medal of St. George 1st class

Medal of St. George 1st class

Soviet Order of Glory 3rd class

Soviet Order of Glory 3rd class

60 Years of Ukraine's Liberation from Nazi Invaders Jubilee Medal

60 Years of Ukraine's Liberation from Nazi Invaders Jubilee Medal

50 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War

50 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War Defender of the Motherland Medal (Ukraine) 1999–2015

Defender of the Motherland Medal (Ukraine) 1999–2015

Order of Military Glory (Belarus)

Order of Military Glory (Belarus) Jubilee medal in honor of the 70th anniversary of liberation of Belarus from Nazi invaders

Jubilee medal in honor of the 70th anniversary of liberation of Belarus from Nazi invaders

Guards Badge

Guards badge of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation

Guards badge of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation Guards badge of the Armed Forces of Belarus

Guards badge of the Armed Forces of Belarus.png) Guards badge of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, established in 2005[41], removed in 2016

Guards badge of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, established in 2005[41], removed in 2016 Guards badge for the Soviet Navy

Guards badge for the Soviet Navy

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ribbon of St. George. |

- Russian Guards

- Order of Glory

- Awards and decorations of the Russian Federation

References

- Kashin, Oleg (1 May 2015). "Hunting swastikas in Russia". OpenDemocracy.net.

- Karney, Ihar; Sindelar, Daisy (7 May 2015). "For Victory Day, Post-Soviets Show Their Colors – Just Not Orange And Black". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- "ЛЕНТЫ К ФУРАЖКАМ РЯДОВОГО СОСТАВА". flot.com. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Neve : Голосование. "Георгиевская лента" : Криминальные сводки". forum.guns.ru. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- Указ Президента РФ от 21.07.1992 № 798

- УКАЗ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ об утверждении общевоинских уставов Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации

- "Георгиевская ленточка стартует в Брянске". 2 April 2019.

- Sindelar, Daisy (April 28, 2014). "What's Orange and Black and Bugging Ukraine?". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Активистка Майдана: "Это я сожгла три колорадские ленты" (in Russian). Moskovskij Komsomolets. March 30, 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Ikhlov, Yevgeniy. "О 'ватниках' и лимитрофах (On 'vatniks' and limitrophes)". www.kasparov.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- "Ukraine Bans Russian St. George Ribbon". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- Berdy, Michele A. (2014-07-24). "Talking Smack About Ukrainians and Russians". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- Kramer, Andrew E. (2014-05-04). "Ukraine's Reins Weaken as Chaos Spreads". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- [112.international/ukraine-top-news/fight-over-saint-george-ribbon-took-place-in-armed-forces-house-today-14927.html "Fight over Saint George ribbon took place in Armed Forces House today"]

- Anatoly Korolev and Dmitry Kosyrev (11 June 2007). "National symbolism in Russia: the old and the new". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "СТАТУТ ВОЕННОГО ОРДЕНА СВЯТОГО ВЕЛИКОМУЧЕНИКА и ПОБЕДОНОСЦА ГЕОРГИЯ".

- Alexei Rudevich (25 April 2014). 5 фактов о георгиевской ленте [5 Facts about the Saint George Ribbon]. Russia7 (in Russian). Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Mikhail Medvedev (8 May 2017). Георгиевская ленточка: победа прихоти над культурой [Ribbon of Saint George: fads prevail over culture]. Saint George (in Russian). Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Ukraine breaks from Russia in commemorating victory". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

“In the 1960-70s there were no St. George’s Ribbons seen during the Victory Day parades. If someone showed up with a ribbon, it would be a violation.

- Георгиевская ленточка на старых (советских) открытках [Ribbon of Saint George in old (Soviet) postcards] (in Russian). 21 December 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Russia awash with symbols of WW2 victory, BBC News 8 May 2015

- Malgin, Andrei (April 16, 2014). "The Black and Orange Ribbon of Putin's Army". The Moscow Times.

- В Москве облили зеленкой Улицкую (in Russian). Lenta.ru. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Crowd wearing nationalist symbols attacks children's school competition organized by historical society Memorial — Meduza". Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Meduza correspondent assaulted by member of crowd disrupting Memorial society young scholar awards — Meduza". Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Putin's ultranationalist base takes aim at the West". Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Bigg, Claire (May 6, 2014). "Kyiv Ditches Separatist-Linked Ribbon As WWII Symbol". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- "Ukraine's Reins Weaken as Chaos Spreads", The New York Times(4 May 2014).

- (in Ukrainian) Lyashko in Lviv poured green, Ukrayinska Pravda (18 June 2014).

- "Кировоградские ветераны отказались от георгиевских лент на 9 мая : Новости УНИАН". Unian.net. 2014-04-23. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- "Председатель Черкасской ОГА призвал отказаться на 9 мая от георгиевских лент : Новости УНИАН". Unian.net. 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- Yaffa, Joshua. "Vladimir Putin's Victory Day in Crimea". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- "Ukrainian Lawmakers Back Ban On Ribbon Embraced As Patriotic Symbol In Russia". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Георгиевская лента напугала Лукашенко". Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Russians embrace Kremlin-backed WWII ribbon". Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Pro-Russia parade planned for city riles local Ukrainians". WinnipegFreePress. 9 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Черно-оранжевые ленты не будут использоваться в ходе празднования Дня Победы в Казахстане. (in Russian). Dialog.kz. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Latvia proposes ban on Russian St. George's ribbon". Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- "Lithuanian faction: St. George Ribbon a symbol of 'Russian aggression and imperialist ambitions'". Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Указ Президента РФ от 21.07.1992 № 798 — Викитека". ru.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070908224552/http://www.mil.gov.ua/index.php?part=breastplate&sub=guards&lang=ua (archived version, sep 8, 2007)