Klondike Mountain Formation

The Klondike Mountain Formation is an Early Eocene (Ypresian)[1][2] geological formation located in the northeast central area of Washington state. The formation, named for the type location designated in 1962, Klondike Mountain north of Republic, Washington,[3] is composed of volcanic rocks in the upper unit and volcanics plus lacustrine (lakebed) sedimentation in which a lagerstätte with exceptionally well-preserved[4] plant and insect fossils has been found, along with fossil epithermal hot springs.[5]

| Klondike Mountain Formation Stratigraphic range: Ypresian 50.1–48.9 Ma | |

|---|---|

Klondike Mountain Formation outcrop at site A0307 | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Okanagan Highlands |

| Sub-units | Tom Thumb Tuff, Lower & Upper Members |

| Underlies | Glacial deposits |

| Overlies | Sanpoil Volcanics & others |

| Thickness | up to 3,200 ft (980 m) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Variable |

| Other | See text |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 48.7°N 118.7°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 54.4°N 101.9°W |

| Region | Okanagan highlands |

| Country | |

| Extent | Okanagan highlands |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Klondike Mountain |

| Named by | Muessig |

| Year defined | 1962 |

Klondike Mountain Formation (the United States)  Klondike Mountain Formation (Washington (state)) | |

The formation is the youngest in a group of formations which belong to the Challis Sequence rocks. The formation unconformably overlies rocks of the Eocene Sanpoil Volcanics and much older Triassic and Permian formations. The formation is bounded on its edges by a series of high-angle strike slip faults, which have contained the Klondike Mountain Formation in a series of graben structures, such as the Republic Graben.[6]

Extent

The formation is located in northern Ferry County, Washington, with the majority of the sedimentation in the Republic and Curlew Basins on the east and in the Toroda Creek area to the north west. The town of Republic, Washington is situated at the southern end of the formation, with outcrops within the city itself. The Curlew basin is situated north of Republic, with the northern edge along the Kettle River and the community of Curlew, Washington near the northeastern edge.[7]

The formation is the southernmost of a string of preserved Eocene highland lakebeds in Washington state and British Columbia.[8] The lake system, within the Okanagan highlands, extends from the Klondike Mountain Formation north approximately 1,000 kilometres (1,000,000 m) in to southern central British Columbia.[1]

Age

Early dating of the formation was based primarily on identification and correlation of the fossils found in the Tom Thumb Tuff, with Joseph Umpleby in 1910 reporting a putative age of Early Miocene. This date was based in examination of fossils by C. R. Eastman, who thought them to be similar to those found in the Florissant Formation of Colorado, which at the time was also considered Miocene. This age was retained in the 1928 work of Edward W. Berry, who included the Klondike Mountain Formation fossil lakebeds as part of the Latah Formation.[9] The age of the Formation has been revised in the following hundred years, with Roland W. Brown identifying the deposits as being older than the Latah Formation in 1936.[10] In a later written communication circa 1958, Brown again revised the age still older, stating the fossils found in the area of Mount Elizabeth indicated an Oligocene age. This age was used by R.L. Parker and J. A. Calkins in their 1964 work on the Curlew Quadrangle of Ferry County.[11] Since then the fossil-bearing strata of the Formation have been radiometrically dated, to give a current estimate of the Ypresian, the mid stage of the early Eocene,49.4 ± .5 million years ago.[1]

Lithology

Parker and Calkins in 1964 noted the association of the Klondike Mountain Formation with the gold and silver deposits of the Republic District and suggested it as a potential host to more ore deposits in the Curlew Quadrangle.[11] The epithermal gold deposits occurring in the Sanpoil volcanics terminate directly below the unconformity where the volcanics contact the base of the Klondike Mountain Formation[12] or sometimes penetrate into the Formation's lowest unit.[5] Hydrothermal sinter deposits are known from the lowest portions of the Formation and are thought to represent hydrothermal eruption areas.[5] In general the lower portions of the Formation have a large amount of hydrothermal alteration, and areas around vents are rich in pyrite and silica. two products of natural hydrothermic sintering. The areas above that show a transition to mudstones, siltstones and sandstones grading from fine-grained material into coarser materials moving up the strata column. The finely-bedded stones show the greatest numbers of fossils and the finest preservation of details.[13]

Paleobiota

The lake bed sediments preserve a diverse array of plants, insects, and fishes, notably the biota called the Republic flora. The Okanagan lake system, which includes the Klondike Mountain Formation, has been classified as one of the great Canadian lagerstätten.[4] The paleoenvironment preserved in the lake deposits is that of a mesic forest, similar in rainfall to that found today along the modern Washington State and British Columbia coast. The climate of the region offered a moderate amount of summer heat, with chilly winters not cold enough to sustain snow cover (a lower mesothermal to upper microthermal climate).[4]

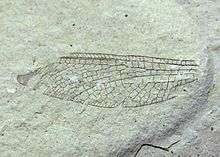

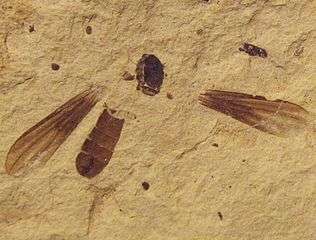

Over a dozen different Rosaceae genera, both extant and extinct, have been identified in the formation. These fossils are some of the oldest reliable macrofossils (excluding ancient fossil pollen) for the family.[14] Fossils of Sorbus genus and Rhus genus leaves that show evidence of being interspecies hybrids have been noted from the formation. Flynn, DeVore and Pigg in 2019 described four species of sumac which formed multiple hybrids.[15] The neuropteran insects (lacewings and their allies) identified as of 2014 include species from the families Berothidae, Chrysopidae, Hemerobiidae, Ithonidae (including Polystoechotidae), Nymphidae, Osmylidae, and Psychopsidae.[1] A number of mecopteran species belonging to the families Cimbrophlebiidae, Dinopanorpidae, Eorpidae, and Panorpidae are also known.[16]

Conifers, ferns, and ginkophytes

| Name | Authority | Year | Family | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shorn & Wehr, 1986 |

1986 |

Oldest true fir described |

| ||

|

Arnold, 1955 |

1955 |

A mosquito fern |

| ||

|

2002 |

A ginkgo |

| |||

|

Mustoe, 2002 |

2002 |

A ginkgo |

| ||

|

1987 |

A dawn redwood |

| |||

|

Pinus latahensis[9] |

Berry, 1929 |

1929 |

A 5 needle pine |

||

|

"Pinus macrophylla"[9] |

Berry, 1929 |

1929 |

A 3 needle pine, jr homoym to Pinus macrophylla Lindley 1839 |

"Pinus macrophylla" | |

|

Pinus monticolensis[9] |

Berry, 1929 |

1929 |

A pine seed morphogenus |

||

|

Pinus tetrafolia[9] |

Berry, 1929 |

1929 |

A possible 4 needled pine, |

||

|

1935 |

A coast redwood, |

| |||

|

(Sternberg) Heer, 1855 |

1929 |

||||

|

(Knowlton) LaMotte, 1926 |

1929 |

A plum-yew relative |

|||

Flowering plants

| Name | Authors | Year | Family | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acer arcticum[23] |

Heer, 1876 |

1987 |

A maple |

||

|

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

|||

|

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

|||

|

Acer spitzi[23] |

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

||

|

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

|||

|

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

|||

|

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

|||

|

Acer wehri[23] |

Wolfe & Tanai, 1987 |

1987 |

A maple |

||

|

Alnus parvifolia[21] |

(Berry) Wolfe & Wehr, 1929 |

1929 |

An Alder |

Alnus parvifolia | |

|

Barghoornia oblongifolia[21] |

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

An extinct Bursera relative |

Barghoornia oblongifolia | |

|

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

A birch |

| ||

|

Bohlenia americana[21] |

(Brown) Wolf & Wehr, 1935 |

1935 |

An extinct sapindale |

Bohlenia americana | |

|

Cercidiphyllum obtritum[21] |

(Dawson) Wolfe & Wehr, 1890 |

1935 |

A katsura |

Cercidiphyllum obtritum | |

|

Comptonia columbiana[21] |

Dawson, 1890 |

1890 |

Comptonia columbiana | ||

|

Concavistylon wehrii[24] |

Manchester et al., 2018 |

2018 |

A Trochodendrale |

||

|

Radtke, Pigg, & Wehr, 2001 |

2001 |

||||

|

Pigg, Manchester, & Wehr, 2003 |

2003 |

Betulaceae |

A hazel nut |

| |

|

Cruciptera simsonii[26] |

(Brown) |

1991 |

A walnut family relative. |

||

|

Dillhoffia cachensis[27] |

Manchester & Pigg, 2008 |

2008 |

A flower of unknown relationships |

Dillhoffia cachensis | |

|

Dipteronia brownii[28] |

McClain & Machester, 2001 |

2001 |

Sapindaceae |

Dipteronia brownii | |

|

Brown, 1940 |

1997 |

A "hard rubber tree" |

| ||

|

Fagopsis undulata[21] |

(Knowlton) Hollick, 1899 |

1987 |

A beech |

Fagopsis undulata | |

|

Fagus langevinii[30] |

Manchester & Dillhoff, 2004 |

2004 |

A beech |

||

|

(Mathewes & Brooke) Manchester |

A chocolate relative |

Florissantia quilchenensis | |||

|

Radtke, Pigg, & Wehr, 2005 |

2005 |

Hamamelidaceae |

A witch alder |

| |

|

Koelreuteria dilcheri[31] |

Wang et al., 2012 |

2012 |

A Koelreuteria species |

Koelreuteria dilcheri | |

|

Langeria magnifica[21] |

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

A witch hazel relative |

Langeria magnifica | |

|

Macginitiea gracilis[21] |

(Lesquereux) Wolfe & Wehr |

1929 |

Macginitiea gracilis | ||

|

DeVore, Taylor, & Pigg, 2015 |

2015 |

Nuphar carlquistii seeds | |||

|

Oemleria janhartfordae[14] |

Benedict, DeVore, & Pigg, 2011 |

2011 |

An Osoberry |

||

|

Bogner, Johnson, Kvaček & Upchurch, 2007 |

2007 |

Araceae |

A golden club |

| |

|

Palaeocarpinus barksdaleae[25] |

Pigg, Manchester, & Wehr, 2003 |

2003 |

Betulaceae |

A birch relative |

Palaeocarpinus barksdaleae |

|

Paleoallium billgenseli[34] |

Pigg, Bryan, & DeVore, 2018 |

2018 |

An onion relative |

Paleoallium billgenseli | |

|

Manchester et al., 2018 |

2018 |

||||

|

Photinia pageae[21] |

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

Rosacaea |

A Christmas-berry relative |

Photinia pagae |

|

Populus lindgreni[9] |

Knowlton, 1898 |

1929 |

|||

|

Prunus cathybrownae[14] |

Benedict, DeVore, & Pigg, 2011 |

2011 |

A cherry relative |

Prunus cathybrownae | |

|

Pteronepelys wehrii[35] |

Manchester |

1994 |

A samara of uncertain affinities. |

Pteronepelys wehrii | |

|

Republica hickeyi[21] |

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

incertae seids |

An incertae sedis angiosperm |

Republica hickeyi |

|

Flynn, DeVore, & Pigg, 2019 |

2019 |

A sumac, |

| ||

|

Rhus garwellii[15] |

Flynn, DeVore, & Pigg, 2019 |

2019 |

A sumac, |

||

|

(Wolfe and Wehr) Flynn, DeVore and Pigg |

1987 |

A sumac, |

| ||

|

Flynn, DeVore, & Pigg, 2019 |

2019 |

A sumac, |

|||

|

Berry, 1929 |

1929 |

| |||

|

Schoepfia republicensis[21] |

(LaMotte) Wolfe & Wehr, 1944 |

1929 |

A Schoepfia relative |

Schoepfia republicensis | |

|

Pigg et al., 2007 |

2018 |

A Trochodendrale, |

| ||

|

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

Malvaceae |

A Linden |

| |

|

Pigg, Wehr, & Ickert-Bond, 2001 |

2001 |

| |||

|

Wolfe & Wehr, 1987 |

1987 |

A dove-tree relative |

| ||

|

Ulmus chuchuanus[37] |

(Berry) LaMotte, 1926 |

2005 |

An elm species |

||

|

Denk & Dillhoff, 2005 |

2005 |

An elm species |

| ||

Insects

| Name | Authors | Year | Family | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adamsochrysa wilsoni[38] |

Makarkin & Archibald |

2013 |

A green lacewing |

||

|

Makarkin & Archibald |

2014 |

A possible psychopsid lacewing |

Ainigmapsychops inexspectatus | ||

|

Allorapisma chuorum[39] |

Makarkin & Archibald |

2009 |

Allorapisma chuorum | ||

|

Antiquiala snyderae[40] |

Archibald & Cannings |

2019 |

|||

|

Cimbrophlebia brooksi[16] |

Archibald |

2009 |

Cimbrophlebiidae |

A Cimbrophlebiid scorpionfly |

Cimbrophlebia brooksi |

|

Cimbrophlebia westae[16] |

Archibald |

2009 |

Cimbrophlebiidae |

A Cimbrophlebiid scorpionfly |

Cimbrophlebia westae |

|

Dinokanaga andersoni[41] |

Archibald |

2005 |

A scorpion fly species |

Dinokanaga andersoni | |

|

Dinokanaga dowsonae[41] |

Archibald |

2005 |

A scorpion fly species |

||

|

Dinokanaga sternbergi[41] |

Archibald |

2005 |

A scorpion fly species |

||

|

Eoceneithycerus carpenteri[42] |

Legalov |

2013 |

|||

|

Eoprephasma hichensi[43] |

Archibald & Bradler |

2015 |

Susumanioidea |

A stick insect species |

|

|

Archibald, Mathewes, & Greenwood |

2013 |

A mecopteran scorpionfly |

Eorpa elverumi | ||

|

Archibald, Mathewes, & Greenwood |

2013 |

A mecopteran scorpionfly, tentatively identified |

Possible E. ypsipeda[44] | ||

|

Idemlinea versatilis[40] |

Archibald & Cannings |

2019 |

|||

|

Klondikia whiteae[45] |

Dlussky & Rasnitsyn |

2003 |

An ant |

||

|

Metanephrocerus belgardeae[46] |

Archibald, Kehlmaier, & Mathewes |

2014 |

Metanephrocerus belgardeae | ||

|

Archibald, Cover, & Moreau |

2006 |

A bulldog ant form genus |

Myrmeciities sp. | ||

|

Sinitchenkova |

1999 |

A mayfly |

|||

|

Archibald, Makarkin, & Ansorge |

2009 |

| |||

|

Oecophylla kraussei[50] |

(Dlussky & Rasnitsyn) |

1999 |

An ant, described as Camponotites kraussei, |

||

|

Palaeopsychops marringerae[52] |

Archibald & Makarkin, 2006 |

2006 |

A giant lacewing |

Palaeopsychops marringerae | |

|

Palaeopsychops timmi[52] |

Archibald & Makarkin, 2006 |

2006 |

A giant lacewing |

Palaeopsychops timmi | |

|

Polystoechotites barksdalae[47] |

Archibald & Makarkin, 2006 |

2006 |

A giant lacewing |

Polystoechotites barksdalae | |

|

Polystoechotites falcatus[47] |

Archibald & Makarkin, 2006 |

2006 |

A giant lacewing |

Polystoechotites falcatus | |

|

Polystoechotites lewisi[47] |

Archibald & Makarkin, 2006 |

2006 |

A giant lacewing |

Polystoechotites lewisi | |

|

Makarkin, Archibald, & Oswald |

2003 |

A hemerobiid lacewing, originally placed in Cretomerobius, |

|||

|

Propalosoma gutierrezae[50] |

Dlussky & Rasnitsyn |

1999 |

An ant, described as a Rhopalosomatidae wasp, |

Propalosoma gutierrezae | |

|

Ulteramus republicensis[57] |

Archibald & Rasnitsyn |

2015 |

A parasitic wasp |

||

|

Ypshna brownleei[40] |

Archibald & Cannings |

2019 |

|||

Vertebrates

| Name | Authors | Year | Family | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Wilson |

1977 |

A bowfin |

|||

|

Wilson |

1977 |

A sucker |

Amyzon aggregatum | ||

|

Wilson |

1977 |

A Salmon |

Eosalmo driftwoodensis | ||

|

Wilson |

1978 |

A mooneye |

Hiodon woodruffi | ||

|

Wilson |

1979 |

References

- Makarkin, V.; Archibald, S.B. (2014). "An unusual new fossil genus probably belonging to the Psychopsidae (Neuroptera) from the Eocene Okanagan Highlands, western North America". Zootaxa. 3838 (3): 385–391. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.1185. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3838.3.8. PMID 25081783.

- Radtke, M.G.; Pigg, K.B.; Wehr, W.C. (2005). "Fossil Corylopsis and Fothergilla Leaves (Hamamelidaceae) from the Lower Eocene Flora of Republic, Washington, U.S.A., and Their Evolutionary and Biogeographic Significance". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 166 (2): 347–356. doi:10.1086/427483.

- Muessig, Siegfried (1962). "Tertiary volcanic and related rocks of the Republic area, Ferry County, Washington". Geological Survey Research 1962. 450 D: D56–58.

- Archibald, SB; Greenwood, DR; Smith, RY; Mathewes, RW; Basinger, JF (2012). "Great Canadian Lagerstätten 1. Early Eocene Lagerstätten of the Okanagan Highlands (British Columbia and Washington State)". Geoscience Canada. 38 (4): 155–164.

- Lasmanis, R (1996). "A historical perspective on ore formation concepts, Republic Mining District, Ferry County, Washington". Washington Geology. 24 (2): 8–11.

- Cheney, ES; Rasmussen, MG (1996). "Regional geology of the Republic area". Washington Geology. 24 (2): 3–7.

- Gaylord, DR; Suydam, JD; Price, SM; Matthews, JM; Lindsey, KA (1996). "Depositional history of the uppermost Sanpoil Volcanics and Klondike Mountain Formation in the Republic basin". Washington Geology. 24 (2): 15–18.

- Suydam, J.; Gaylord, D.R. (1997). "Toroda Creek half graben, northeast Washington: Late-stage sedimentary infilling of a synextensional basin". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 109 (10): 1333–1348. Bibcode:1997GSAB..109.1333S. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1997)109<1333:tchgnw>2.3.co;2.

- Berry, E.W. (1929). "A revision of the flora of the Latah Formation". USGS Professional Paper. PP 154-H: 225–265.

- Brown, R.W. (1936). "Additions to some fossil floras of the western United States". USGS Professional Paper. PP 186-J.

- Parker, RL; Calkins, JA (1964). "Geology of the Curlew Quadrangle, Ferry County, Washington". Geological Survey Bulletin. 1169.

- Boleneus, DE; Raines, GL; Causey, JD; Bookstrom, AA; Frost, TP; Hyndman, PC (2001). "Assessment method for epithermal gold deposits in northeast Washington State using weights-of-evidence GIS modeling" (PDF). USGA Open File Report. 01-501: 1–52.

- Gaylord, DR; Price, SM; Suydam, JD (2001). Volcanic and hydrothermal influences on middle Eocene lacustrine sedimentary deposits. Republic Basin, northern Washington, USA. International Association of Sedimentologists Special Publication. pp. 199–222. ISBN 9781444304268.

- Benedict, JC; DeVore, ML; Pigg, KB (2011). "Prunus and Oemleria (Rosaceae) Flowers from the Late Early Eocene Republic Flora of Northeastern Washington State, U.S.A.". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 172 (7): 948–958. doi:10.1086/660880.

- Flynn, S.; DeVore, M. L.; Pigg, K. B. (2019). "Morphological Features of Sumac Leaves (Rhus, Anacardiaceae), from the Latest Early Eocene Flora of Republic, Washington". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 180 (6): 464–478. doi:10.1086/703526.

- Archibald, S. B. (2009). "New Cimbrophlebiidae (Insecta: Mecoptera) from the Early Eocene at McAbee, British Columbia, Canada and Republic, Washington, USA" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2249: 51–62. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2249.1.5.

- Schorn, Howard; Wehr, Wesley (1986). "Abies milleri, sp. nov., from the Middle Eocene Klondike Mountain Formation, Republic, Ferry County, Washington". Burke Museum Contributions in Anthropology and Natural History (1): 1–7.

- Arnold, C. A. (1955). "A Tertiary Azolla from British Columbia" (PDF). Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. 12 (4): 37–45.

- Mustoe, G.E. (2002). "Eocene Ginkgo leaf fossils from the Pacific Northwest". Canadian Journal of Botany. 80 (10): 1078–1087. doi:10.1139/b02-097.

- Chaney, R.W. (1951). "A revision of fossil Sequoia and Taxodium in western North America based on the recent discovery of Metasequoia". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 40 (3): 231.

- Wolfe, J.A.; Wehr, W.C. (1987). "Middle Eocene dicotyledonous plants from Republic, northeastern Washington". United States Geological Survey Bulletin. 1597: 1–25.

- LaMotte, R.S. (1944). "Supplement to catalogue of Mesozoic and Cenozoic plants of North America, 1919–37". United States Geological Survey Bulletin. 924: 307.

- Wolfe, J.A.; Tanai, T. (1987). "Systematics, Phylogeny, and Distribution of Acer (maples) in the Cenozoic of Western North America". Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University. Series 4, Geology and Mineralogy. 22 (1): 1–246.

- Manchester, S.; Pigg, K. B.; Kvaček, Z; DeVore, M. L.; Dillhoff, R. M. (2018). "Newly recognized diversity in Trochodendraceae from the Eocene of western North America". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 179 (8): 663–676. doi:10.1086/699282.

- Pigg, K.B.; Manchester S.R.; Wehr W.C. (2003). "Corylus, Carpinus, and Palaeocarpinus (Betulaceae) from the Middle Eocene Klondike Mountain and Allenby Formations of Northwestern North America". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 164 (5): 807–822. doi:10.1086/376816.

- Manchester, S. R. (1991). "Cruciptera, a new Juglandaceous winged fruit from the Eocene and Oligocene of western North America". Systematic Botany. 16 (4): 715–715.

- Manchester, S.; Pigg, K. (2008). "The Eocene mystery flower of McAbee, British Columbia". Botany. 86 (9): 1034–1038. doi:10.1139/B08-044.

- McClain, A. M.; Manchester, S. R. (2001). "Dipteronia (Sapindaceae) from the Tertiary of North America and implications for the phytogeographic history of the Aceroideae". American Journal of Botany. 88 (7): 1316–25. doi:10.2307/3558343. JSTOR 3558343. PMID 11454632.

- Call, V.B.; Dilcher, D.L. (1997). "The fossil record of Eucommia (Eucommiaceae) in North America" (PDF). American Journal of Botany. 84 (6): 798–814. doi:10.2307/2445816. JSTOR 2445816. PMID 21708632.

- Manchester, S. R.; Dillhoff, R. M. (2004). "Fagus (Fagaceae) fruits, foliage, and pollen from the Middle Eocene of Pacific Northwestern North America". Canadian Journal of Botany. 82 (10): 1509–1517. doi:10.1139/b04-112.

- Wang, Q.; Manchester, S. R.; Gregor, H. J.; Shen, S.; Li, Z. Y. (2013). "Fruits of Koelreuteria (Sapindaceae) from the Cenozoic throughout the northern hemisphere: their ecological, evolutionary, and biogeographic implications". American Journal of Botany. 100 (2): 422–449. doi:10.3732/ajb.1200415. PMID 23360930.

- DeVore, ML; Taylor, W; Pigg, KB (2015). "Nuphar carlquistii sp. nov. (Nymphaeaceae): A Water Lily from the Latest Early Eocene, Republic, Washington". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 176 (4): 365–377. doi:10.1086/680482.

- Bogner, J.; Johnson, K. R.; Kvacek, Z.; Upchurch, G. R. (2007). "New fossil leaves of Araceae from the Late Cretaceous and Paleogene of western North America" (PDF). Zitteliana. A (47): 133–147. ISSN 1612-412X.

- Pigg, K. B.; Bryan, F. A.; DeVore, M. L. (2018). "Paleoallium billgenseli gen. et sp. nov.: fossil monocot remains from the latest Early Eocene Republic Flora, northeastern Washington State, USA". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 179 (6): 477–486. doi:10.1086/697898.

- Manchester, S.R. (1994). "Fruits and Seeds of the Middle Eocene Nut Beds Flora, Clarno Formation, Oregon". Palaeontographica Americana. 58: 30–31.

- Pigg, K.B.; Wehr, W.C.; Ickert-Bond, S.M. (2001). "Trochodendron and Nordenskioldia (Trochodendraceae) from the Middle Eocene of Washington State, U.S.A.". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 162 (5): 1187–1198. doi:10.1086/321927.

- Denk, T.; Dillhoff, R.M. (2005). "Ulmus leaves and fruits from the Early-Middle Eocene of northwestern North America: systematics and implications for character evolution within Ulmaceae" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Botany. 83 (12): 1663–1681. doi:10.1139/b05-122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09.

- Vladimir N. Makarkin; S. Bruce Archibald (2013). "A Diverse New Assemblage of Green Lacewings (Insecta, Neuroptera, Chrysopidae) from the Early Eocene Okanagan Highlands, Western North America". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (1): 123–146. doi:10.1666/12-052R.1.

- Makarkin, V. N.; Archibald, S. B. (2009). "A new genus and first Cenozoic fossil record of moth lacewings (Neuroptera: Ithonidae) from the Early Eocene of North America" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2063: 55–63. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2063.1.3.

- Archibald, S. B.; Cannings, R. A. (2019). "Fossil dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera) from the early Eocene Okanagan Highlands, western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 151 (6): 783–816. doi:10.4039/tce.2019.61.

- Archibald, S.B. (2005). "New Dinopanorpidae (Insecta: Mecoptera) from the Eocene Okanagan Highlands (British Columbia, Canada and Washington State, USA)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (2): 119–136. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42..119A. doi:10.1139/e04-073.

- Legalov, A. A. (2013). "New and little known weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) from the Paleogene and Neogene". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 25 (1): 59–80. doi:10.1080/08912963.2012.692681.

- Archibald, SB; Bradler, S (2015). "Stem-group stick insects (Phasmatodea) in the early Eocene at McAbee, British Columbia, Canada, and Republic, Washington, United States of America". Canadian Entomologist. 147 (6): 744. doi:10.4039/tce.2015.2.

- Archibald, SB; Mathewes, RW; Greenwood, DR (2013). "The Eocene apex of panorpoid scorpionfly family diversity". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (4): 677–695. doi:10.1666/12-129.

- Dlussky, G. M.; Rasnitsyn, A. P. (2003). "Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Formation Green River and some other Middle Eocene deposits of North America". Russian Entomological Journal. 11 (4): 411–436.

- Archibald, SB; Kehlmaier, C; Mathewes, RW (2014). "Early Eocene big headed flies (Diptera: Pipunculidae) from the Okanagan Highlands, western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 146 (4): 429–443. doi:10.4039/tce.2013.79.

- Archibald, S.B.; Cover, S. P.; Moreau, C. S. (2006). "Bulldog Ants of the Eocene Okanagan Highlands and History of the Subfamily (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae)" (PDF). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 99 (3): 487–523. doi:10.1603/0013-8746(2006)99[487:BAOTEO]2.0.CO;2.

- Sinitchenkova, N. D. (1999). "A new mayfly species of the extant genus Neoephemera from the Eocene of North America (Insecta: Ephemerida=Ephemeroptera)" (PDF). Paleontological Journal. 33 (4): 403–405. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-30.

- Archibald, S. B.; Makarkin, V. N.; Ansorge, J. (2009). "New fossil species of Nymphidae (Neuroptera) from the Eocene of North America and Europe" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2157: 59–68. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2157.1.4.

- Dlussky, G. M.; Rasnitsyn, A. P. (1999). "Two new species of aculeate hymenopterans (Vespida=Hymenoptera) from the Middle Eocene of the United States". Paleontological Journal. 33: 546–549.

- Perfilieva, K. S.; Dubovikoff, D. A.; Dlussky, G. M. (2017). "Miocene ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from Crimea". Paleontological Journal. 51 (4): 391–401. doi:10.1134/S0031030117040098.

- Archibald, S.B.; Makarkin V.N. (2006). "Tertiary Giant Lacewings (Neuroptera: Polystechotidae): Revision and Description of New Taxa From Western North America and Denmark". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 119–155. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001817. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- Winterton, SL; Makarkin, VN (2010). "Phylogeny of Moth Lacewings and Giant Lacewings (Neuroptera: Ithonidae, Polystoechotidae) Using DNA Sequence Data, Morphology, and Fossils". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 103 (4): 511–522. doi:10.1603/an10026.

- Makarkin, VN; Archibald, SB; Oswald, JD (2003). "New Early Eocene brown lacewings (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae) from western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 135 (5): 637–653. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.489.5852. doi:10.4039/n02-122.

- Vladimir N. Makarkin; Sonja Wedmann; Thomas Weiterschan (2016). "A new genus of Hemerobiidae (Neuroptera) from Baltic amber, with a critical review of the Cenozoic Megalomus-like taxa and remarks on the wing venation variability of the family". Zootaxa. 4179 (3): 345–370. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4179.3.2. PMID 27811679.

- Archibald, S. B.; Rasnitsyn, A. P.; Brothers, D. J.; Mathewes, R. W. (2018). "Modernisation of the Hymenoptera: ants, bees, wasps, and sawflies of the early Eocene Okanagan Highlands of western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 150 (2): 205–257. doi:10.4039/tce.2017.59.

- Archibald, S.B.; Rasnitsyn, A.P. (2015). "New early Eocene Siricomorpha (Hymenoptera: Symphyta: Pamphiliidae, Siricidae, Cephidae) from the Okanagan Highlands, western North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 148 (2): 209–228. doi:10.4039/tce.2015.55.

- Wilson, M.V.H.; Li, Guo-Qing (1999). "Osteology and systematic position of the Eocene salmonid †Eosalmo driftwoodensis Wilson from western North America" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 99 (125): 279–311. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1999.tb00594.x. Retrieved 2010-01-01.