Wisconsin River

The Wisconsin River is a tributary of the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. At approximately 430 miles (692 km) long, it is the state's longest river. The river's name, first recorded in 1673 by Jacques Marquette as "Meskousing", is rooted in the Algonquian languages used by the area's American Indian tribes, but its original meaning is obscure. French explorers who followed in the wake of Marquette later modified the name to "Ouisconsin", and so it appears on Guillaume de L'Isle's map (Paris, 1718). This was simplified to "Wisconsin" in the early 19th century before being applied to Wisconsin Territory and finally the state of Wisconsin.

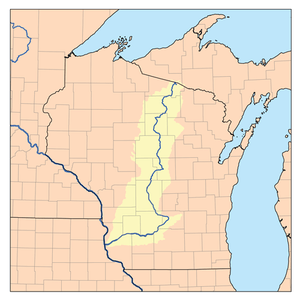

| Wisconsin River | |

|---|---|

Wisconsin and the Wisconsin River | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Lac Vieux Desert |

| • elevation | 1,683 ft (513 m) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Mississippi River near Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin |

| Length | 420 mi (680 km) |

| Basin size | 12,280 sq mi (31,800 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 12,000 cu ft/s (340 m3/s) at mouth |

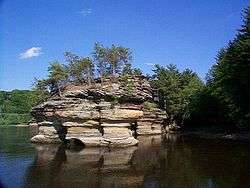

The Wisconsin River originates in the forests of the North Woods Lake District of northern Wisconsin, in Lac Vieux Desert near the border of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It flows south across the glacial plain of central Wisconsin, passing through Wausau, Stevens Point, and Wisconsin Rapids. In southern Wisconsin it encounters the terminal moraine formed during the last ice age, where it forms the Dells of the Wisconsin River. North of Madison at Portage, the river turns to the west, flowing through Wisconsin's hilly Western Upland and joining the Mississippi approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Prairie du Chien.

The highest waterfall on the river is Grandfather Falls in Lincoln County.

Geology

The modern Wisconsin River was formed in several stages. The lower, westward-flowing portion of the river is located in the unglaciated Driftless Area, and this section of the river's course likely predates the rest by several million years. The lower reach of the river is narrower than its upstream valley, leading to the suggestion the upper portions of the ancestor of the river flowed east previous to the Pleistocene.[1] The remaining length of the river was formed gradually as glaciers advanced and retreated over Wisconsin. The stretch of river from Stevens Point north to Merrill was a drainage route for meltwater flowing away from the glaciers which covered northern Wisconsin during the Wisconsin Glaciation. As the glaciers retreated further northward, the river also grew in that direction. South from Stevens Point, the meltwater would have flowed into Glacial Lake Wisconsin, a prehistoric proglacial lake that existed in the central part of the state. As temperatures warmed around 15,000 years ago, the ice dam holding the lake in place burst, unleashing a catastrophic flood that carved the Dells of the Wisconsin River and joined the upper stretches of the river with the pre-existing lower river valley that today flows from Portage to Prairie du Chien.

History

In the summer of 1673, French missionary Jacques Marquette, French-Canadian explorer Louis Joliet, and their crew of five Metis arrived near the headwaters of the Fox River. From there, they were told to portage their two canoes a distance of slightly less than two miles through marsh and oak plains to the Wisconsin River. "The river on which we embarked is called Meskousing," wrote Marquette. "It is very wide; it has a sandy bottom, which forms various shoals that render its navigation very difficult." In his only other reference to the river, Marquette says that the Mississippi is "narrow at the place where Miskous empties."[2] After they returned, Joliet used the name "Miskonsing" on a map that he drew in 1674, and when the news of their voyage was first published in 1681 the book's author, Melchisedec Thevenot, called it the "Mescousin" River.

The name used today was born when the explorer Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, misread Marquette's initial M, which was written by hand in cursive script, "Ou" in 1674.[3] This found its way onto printed maps, even though in a report written in 1682 La Salle tried to correct himself: "On the east one comes first to the river called by the Savages Ouisconsing, or Misconsing, which flows from the east." Over the next two decades the initial M completely disappeared as writers and mapmakers always called the river by some version that began with a vowel. For the next 150 years the river, and by extension our part of the world generally, was known as "Ouisconsin." Sloppy printers sometimes turned this into Ouriconsing, Ouiscousen, and even Ouiskonche (the first of which may have been the origin of the toponym "Oregon"), but the "Ouis …" spelling was the one most often used by both French and English writers until the mid-19th century.

As American soldiers and officials traveled through the area for the first time following the War of 1812, they initially used the French spelling. But when large numbers of lead miners streamed into the country south of the river in the 1820s, the U.S. government began to refer to it differently in debates and legislation. These legal documents created by the government in Washington sometimes used the French spelling, but they gradually introduced the uniquely American, "Wisconsin." The U.S. House of Representatives Journal was the first to print it (in the entry for February 1, 1830), during discussion of "laying out a town at Helena, on the Wisconsin river, in the Territory of Michigan …" In the five years that followed, the modern spelling was used with increasing frequency in government publications as well as in commercially published books and maps. In 1836, when territorial status was authorized on July 4, the name became officially "Wisconsin" (though Canadian and French writers often used "Ouisconsin" until the end of the 19th century).

Oddly, the person who did the most to create Wisconsin Territory didn't like the name. James Duane Doty, who first visited the region in 1820, was the principal advocate for the spelling "Wiskonsan", which shows up dozens of times through the early 1840s. "During all this time, Governor Doty and the legislature were in constant hostility," wrote contemporary observer Theodore Rodolf. "One of the governor's vagaries had to be settled by a joint resolution. The governor had a fondness for spelling the name of the territory as "Wiskonsan." The Legislature, in order to avoid future embarrassments and misunderstandings, found itself obliged to declare by a joint resolution that the spelling used in the organic act should be maintained."[4]

The first documented exploration of the Wisconsin River by Europeans took place in 1673, when Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet of France canoed from Lake Michigan up the Fox River until reaching the present-day site of Portage in early June. At this location the Wisconsin and Fox rivers are only 2 miles (3.2 km) distant, so the explorers could portage from the Fox to the Wisconsin River. They then continued downstream 200 miles (320 km) to the Wisconsin's mouth, entering the Mississippi on June 17. Other explorers and traders would follow the same route, and for the next 150 years the Wisconsin and Fox rivers, collectively known as the Fox-Wisconsin Waterway, formed a major transportation route between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River.

Industry began to form on the Wisconsin in the early 19th century, as loggers started using the river to raft logs downstream from northern forests to sawmills in new cities like Wausau. By the 1880s, logging companies were damming the river to ensure the river had enough capacity for the logs being floated downstream. Later, at the start of the 20th century, more dams were constructed to provide for flood control and hydroelectricity. The dams also spurred tourism, creating reservoirs such as Lake Wisconsin that are popular areas for recreational boating and fishing. Today the Wisconsin River is the hardest working river in the nation. There are 25 operating Hydroelectric Power Plants on the Wisconsin River. The "hydros" harness 645 feet of the rivers fall to generate nearly one billion kilowatt hours of renewable electricity a year - enough energy to supply the residential needs of over 300,000 people without creating any pollution.

Despite this, a 93-mile (150 km) stretch of the Wisconsin between its mouth and the hydroelectric dam at Prairie du Sac is free of any dams or barriers and is relatively free-flowing. In the late 1980s, this portion of the river was designated as a state riverway, and development alongside the river has been limited to preserve its scenic integrity.

Navigable river of the United States

The Wisconsin River is a "navigable river of the United States." This designation primarily means that the federal government has jurisdiction for dams on the river. Dams that include hydropower facilities are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Courts have ruled that despite the fact that the river lies entirely in one state, it nevertheless historically carried goods to markets in other states and therefore is subject to the commerce clause of the United States Constitution. Courts have also ruled that raw logs, even if merely carried via log drives to mills within the state, constitute commerce. On the basis of these judgments, the Wisconsin River is considered a navigable waterway throughout its entire length.[5] This designation does not generally have bearing on recreational use of the river. Boat registrations and fishing licenses are obtained through the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, for example.[6]

Lower Wisconsin River State Riverway

The Lower Wisconsin River State Riverway is a state-funded project designed to protect the southern portion of the Wisconsin River. It extends 93 miles (150 km) from Sauk City to the point where the Wisconsin River empties into the Mississippi, about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of the city of Prairie du Chien. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources manages protected lands of over 75,000 acres (300 km2), including the river itself, islands, and some lands adjacent to the river.

There are no dams or man-made obstructions to the natural flow of water between the hydroelectric dam just north of Sauk City and the confluence of the Wisconsin and the Mississippi. This long stretch of free-flowing river provides important natural habitats for a variety of wildlife, including white-tail deer, otter, beaver, turtles, sandhill cranes, eagles, hawks, and a variety of fish species.

Recreational opportunities on the lower Wisconsin River range from fishing and canoeing to tubing and camping. Canoe camping is particularly popular because of the abundance of suitable sandbars along the riverway and because no permits are required. On summer weekends, naturists can be found on Mazo Beach which is north of the village of Mazomanie. According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, two thirds of river users can be found on the stretch between Prairie du Sac and Spring Green.[7]

Cities and villages along the river

See also

- List of Wisconsin rivers

- Kent, Paul G. and Dudiak, Tamara A. Wisconsin Water Law: A Guide to Water rights and Regulations, Second Edition (University of Wisconsin Extension, 2001). Available on line at http://learningstore.uwex.edu/assets/pdfs/g3622.pdf (11 November 2012).

Notes

- Steven Dutch, "Possible Early Pleistocene Drainage in Wisconsin", Retrieved July 17, 2007

- "Louis Joliet - The Famous Journey". The Mariners' Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- "Wisconsin's Name: Where It Came From and What It Means | Wisconsin Historical Society". www.wisconsinhistory.org. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- "Wisconsin's Name: Where it Came From and What it Means". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- Wisconsin Public Service Corp. v. Federal Power Commission 147 F.2d 743 (1945).

- http://www.nationalrivers.org/states/wi-law.htm

- "Lower Wisconsin State Riverway". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wisconsin River. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Wisconsin River. |

- River Alliance of Wisconsin

- Report on the Wisconsin River by Mark Morgan

- Wisconsin's Name: Where It Came From and What It Means, Wisconsin Historical Society

- Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Board

- Pictures and Information of the Northern Stretch of the Wisconsin River

- Current Wisconsin River Conditions

- Lower Wisconsin River Maps and Mileage