Khor Fakkan

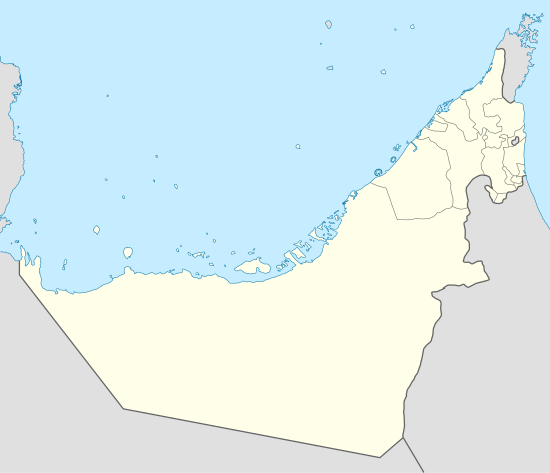

Khor Fakkan (Arabic: خَوْر فَكَّان, romanized: Khawr Fakkān) is a city and exclave of the Emirate of Sharjah, located on the east coast of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), facing the Gulf of Oman, and geographically surrounded by the Emirate of Fujairah. The city, the second largest on the east coast after Fujairah City,[2] is set on the bay of Khor Fakkan, which means "Creek of Two Jaws". It is the site of Khor Fakkan Container Terminal, the only natural deep-sea port in the region and one of the major container ports in the UAE.

Khawr Fakkan خَوْر فَكَّان | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Khor Fakkan | |

| |

Flag | |

Khawr Fakkan Location of Khor Fakkan | |

| Coordinates: 25°20′21″N 56°21′22″E | |

| Country | |

| Emirate | Sharjah |

| Government | |

| • Sheikh | Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 39,515 |

| • Density | 1,150/km2 (3,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (UAE Standard Time) |

History

Khorfakkan has a long history of human settlement. There is evidence of post holes from the wooden uprights of the traditional barasti huts known as areesh, similar to those found at Tell Abraq which dates from the 3rd to 1st millienium BC.[3] Excavations by a team from the Sharjah Archaeological Museum have identified 34 graves and a settlement belonging to the early-mid 2nd millennium BC. These are clustered on rock outcrops overlooking the harbour.

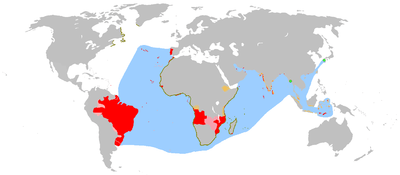

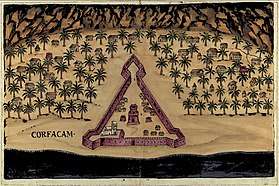

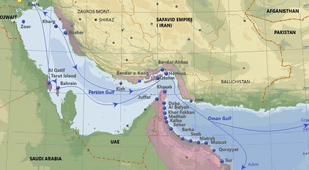

Around 1500, Duarte Barbosa described it as a village “around which are gardens and farms in plenty”.[3] The town was captured by the Portuguese Empire in the 16th century and was referred to as Corfacão. It was part of a serial of fortified cities that the Portugal had to control the access to the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, like Khor Fakan, Muscat, Sohar, Seeb, Qurayyat and Muttrah. The settlement, located on the east coast of the Musandam peninsula, south of the Gulf of Oman, was a tributary of the kingdom of Hormuz. At the dawn of the 16th century, it and its port were defended by a wide walled belt facing the land, closing the gorge that, in the mountain range parallel to the coast, allows communication with the interior. In this monumental structure a single door was torn, defended by a tower. The ensemble was responsible for safeguarding eventual tribal attacks.[4]

In 1580 the Venetian jeweler Gasparo Balbi noted "Chorf" in a list of places on the east coast of the United Arab Emirates, which is considered by historians to indicate Khor Fakkan.[5] The Portuguese built a fort at Khor Fakkan that was a ruin by 1666. The log book of the Dutch vessel the Meerkat mentions this fort and another one, describing "Gorfacan" as a place on a small bay, with about 200 small houses built from date branches, near the beach. It refers to a triangular Portuguese fortress on the northern side, in ruins, and a fortress on a hill on the southern side, also in ruins, without garrison or artillery. As well as date palms, the Meerkat's log also mentions fig trees, melons, watermelons and myrrh. It notes several wells with "good and fresh water" used for irrigation.

One reason suggested for the ruinous state of the forts is an invasion in 1623 of the Persian navy under the control of Omani Sheikh Muhammad Suhari. Suhari, facing a Portuguese counter-attack, withdrew to the Portuguese forts, including that of Khorfakkan. When the Persians were expelled, the Portuguese commander Rui Freire urged the people of Khorfakkan to remain loyal to the Portuguese crown and established a Portuguese customs office as well.

In 1737, long after the Portuguese had been expelled from Arabia, the Persians again invaded Khor Fakkan, with some 5,000 men and 1,580 horses, with the help of the Dutch, during their intervention in the Omani civil war.[6] In 1765 Khor Fakkan belonged to a sheikh of the Al Qasimi, Sharjah's ruling family, according to the German traveler Carsten Niebuhr. There is a map by the French cartographer Rigobert Bonne dating to about 1770 that shows the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf and includes Khor Fakkan.

At the turn of the 19th century, Lorimer notes that Khor Fakkan had about 5,000 date trees and was home to about 150 houses of Naqbiyin and Arabicised Persians, amounting to some 800 people. The population lived by cultivation and pearling and the town had seven shops.[7]

The German submarine U-533 sank about 25 miles (40 km) off the coast on 16 October 1943 during World War II. Divers found the wreck at a depth of 108 metres (354 ft) in 2009.[8]

The modern Khor Fakkan Container Terminal was inaugurated in 1979, and is the only natural deep-sea port in the region, and one of the top ports in the Emirates for containers.[9][10] The Dh 300 million ($81.75 million) project involved reclaiming some 150,000 square metres (1,600,000 sq ft) to increase the storage capacity and to facilitate large cranes, and 16 metres (52 ft) deep quays to accommodate for major vessels over 400 metres (1,300 ft) in length. As of 2004 it handled 1.6 million TEU's.[10][11]

Geography and climate

Khor Fakkan lies on the east coast of the UAE, between the Indian Ocean and the Shumayliyyah[12][13] or Western Hajar Mountains.[14] The bay of Khor Fakkan is north-east facing and is protected from prevailing winds by a jetty serving the container terminal. Tourism is well developed thanks to sandy beaches and the coral reefs that attract many divers. Khor Fakkan Beach lies to the north of the centre of the town.

From November to April Khor Fakkan is sunny and warm during the day; the evenings are cool and humidity low. Daytime temperatures range from 18 to 30 °C (64 to 86 °F). One may expect rain and tropical storms between January and March. The climate warms from May to September with the high temperature at noon in July and August reaching 40 °C (104 °F). The nights too are warm, with the temperature reaching 36 °C (97 °F), with high humidity.

Landmarks

Khor Fakkan has one 4 star holiday beach resort, the Oceanic Hotel.[15] The fish, fruit and vegetable souq is located at the southern end of the corniche and near the main highway.[2]

Gallery

Sunrise over Khor Fakkan beach

Sunrise over Khor Fakkan beach Tourist attraction

Tourist attraction Mosque

Mosque Boat

Boat East view, with the Shumayliyyah or Western Hajar Mountains in the background

East view, with the Shumayliyyah or Western Hajar Mountains in the background View to the western landscape

View to the western landscape

Notable people

- H.E. Sheikh Saeed bin Saqer bin Sultan Al-Qasimi (1962-), a Qasimi royal, Deputy Chairman of the Amiri Court in Khorfakkan

- Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, visual artist

- Hussain Al Jassmi (1979-), Arabic musician

- Fayez Banihammad, United Flight 175 hijacker on September 11, 2001

See also

References

- "Livro das plantas de todas as fortalezas, cidades e povoaçoens do Estado da India Oriental / António Bocarro [1635]" (PDF).

- Carter, Terry; Dunston, Lara (2006). Dubai. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-74059-840-8.

- Agius, Dionisius A. (6 December 2012). Seafaring in the Arabian Gulf and Oman: People of the Dhow. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-136-20182-0.

- "Fortalezas.Org".

- Abed, Ibrahim; Hellyer, Peter (2001). United Arab Emirates: A New Perspective. Trident Press Ltd. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-900724-47-0.

- Hawley, Donald (1 January 1970). The Trucial States. Ardent Media. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-04-953005-8.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 516.

- "Untergang vorm Morgenland". Spiegel Online (in German). 18 December 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- Peck, Malcolm C. (12 April 2010). The A to Z of the Gulf Arab States. Scarecrow Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4617-3190-0.

- United Arab Emirates Yearboook 2006. Trident Press Ltd. 2006. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-905486-05-2.

- The Report: Sharjah 2008. Oxford Business Group. 2008. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-902339-02-3.

- Spalton, J. A.; Al-Hikmani, H. M. (2006). "The Leopard in the Arabian Peninsula – Distribution and Subspecies Status" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 1): 4–8.

- Edmonds, J.-A.; Budd, K. J.; Al Midfa, A. & Gross, C. (2006). "Status of the Arabian Leopard in United Arab Emirates" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 1): 33–39.

- Lancaster, Fidelity; Lancaster, William (2011). Honour is in Contentment: Life Before Oil in Ras Al-Khaimah (UAE) and Some Neighbouring Regions. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 137–238. ISBN 3-1102-2339-2.

- Dubai: The Complete Residents' Guide. Explorer Publishing & Distribution. 1 June 2006. p. 327. ISBN 978-976-8182-76-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khor Fakkan. |