Kallawaya

The Kallawaya are an itinerant group of traditional healers living in the Andes of Bolivia. They live in the Bautista Saavedra region, a mountainous area north of La Paz.[1] They are members of the Mollo culture and are direct descendants of Tiwanaku culture.[2] According to the UNESCO Safeguarding Project, the Kallawaya can be traced to the pre-Inca period.[1] The Kallawaya performed brain surgery as early as 700 CE[3] and knew how to effectively prevent and treat malaria with quinine before the Europeans.[4] They also helped to save thousands of lives during the construction of the Panama Canal.[5] There were 11,662 of them in 2012 throughout Bolivia.[6]

Etymology

According to Enrique Oblitas Poblete, a Bolivian ethnobotanical specialist,[7] Kallawaya may be a corruption of khalla-wayai ("beginning of a drink offering") or k'alla or k'alli wayai ("entrance into priesthood").[8]

Healers

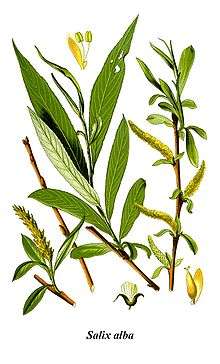

Kallawaya doctors (médicos Kallawaya), are known as the naturopathic healers of Inca kings,[9] and as keepers of science knowledge, principally the pharmaceutical properties of vegetables, animals and minerals.[2] Most Kallawaya healers understand how to use 300 herbs, while specialists are familiar with 600 herbs. Kallawaya women are often midwives, treat gynecological disorders, and pediatric patients.[10] Kallawaya healers travel through northwestern Bolivia and parts of Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Panama, and Peru. Often they are on foot, walking ancient Inca trails, through the tropics, mountain valleys and highland plateaus, while looking for traditional herbs.[11]

Prior to leaving their homes to heal the sick, the Kallawayas perform a ceremonial dance. The dance and regalia are expressed as the yatiri ("healer"). The choreography is noted for the llantucha of suri, clothing made of rhea feathers and used as protection against the elements while they travel to their patients, carrying khapchos ("male bags") that contain herbs, mixes, and talismans.[2] Groups of musicians perform Kantu, playing drums and pan flutes during the ritual ceremonies to establish contact with the spirit world before the healer visits patients.[1]

Language

The language of their trade is the Kallawaya language, a language based on Quechua grammar but retaining an esoteric vocabulary for terms reflecting medicinal knowledge, which appears to be a remnant of the vocabulary of the now extinct Puquina language.[2][12] For general conversation, they speak the more common Quechua language.[13]

References

- "Proclamation 2003: "The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya"". UNESCO. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- "Wisdom of Mollo Culture Kallawaya". boliviacontact.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Preedy, Victor R. (2008). Botanical medicine in clinical practice. CABI. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-1-84593-413-2. Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Howley, Andrew. "Ancient Traditions, Modern Celebration – National Geographic Society (blogs)". newswatch.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2012 Bolivia Características de la Población". Instituto Nacional de Estadística, República de Bolivia. p. 29.

- Browman, David L.; Schwarz, Ronald A. (1979). Spirits, shamans, and stars: perspectives from South America. Mouton. p. 59. ISBN 978-90-279-7890-5. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- International Folk Music Council; Queen's University (Kingston, Ont.). Dept. of Music (1985). Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council. Published for the International Folk Music Council by the University of Illinois Press. p. 162. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- "Kallawaya Healers". sacredheritage.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Lougheed, Vivien; Harris, John (March 1, 2006). Bolivia. Hunter Publishing, Inc. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-1-58843-565-1. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Peterson, Michele (October 30, 2004). "Bewitched in Bolivia". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- Harrison, K. David. "Kallawaya: A Secret language for medicinal knowledge". Swarthmore College Linguistics. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Lovgren, Stefan (September 18, 2007). "Languages Racing to Extinction in 5 Global "Hotspots"". National Geographic. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

Further reading

- Abdel-Malek, S, et al. 1995. Drug Leads from the Kallawaya Herbalists of Bolivia. 1. Background, Rationale, Protocol and Anti-HIV Activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 50, no. 3: 157.

- Bastien, Joseph William. Healers of the Andes: Kallawaya Herbalists and Their Medicinal Plants. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987. ISBN 0-87480-278-4

- Janni, Kevin D, and Joseph W Bastien. 2004. Special Section on Medicinal Plants – Exotic Botanicals in the Kallawaya Pharmacopoeia. Economic Botany. 58: S274.

- Krippner, S., and E. S. Glenney. 1997. The Kallawaya Healers of the Andes. The Humanistic Psychologist : Bulletin of the Division of Humanistic Psychology, Division 32 of the American Psychological Association. 25, no. 2: 212.

External links

- Articles list, various authors, prepared by Dr. K. David Harrison, Swarthmore University

- Encyclopædia Britannica on Kallawaya people

- Encyclopædia Britannica Photo of Kallawaya near Charazani, Bolivia

- Kallawaya by Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages