Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revolution. Similarly, the conspiracy theory of Jewish Communism alleges that Jews have dominated the Communist movements in the world, and is related to The Zionist Occupation Government conspiracy theory (ZOG), which alleges that Jews control world politics.[1]

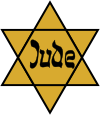

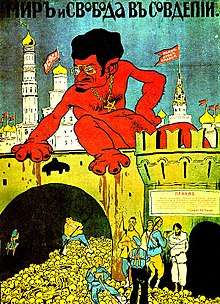

In 1917, after the Russian Revolution, the antisemitic canard was the title of the pamphlet, The Jewish Bolshevism, which featured in the racist propaganda of the anti-communist White movement forces during the Russian Civil War (1918–1922). During the 1930s, the Nazi Party in Germany and the German American Bund in the United States propagated the antisemitic theory to their followers, sympathisers, and fellow travellers.[2][3][4][5] In Poland, the tem "Żydokomuna", was an antisemitic opinion that the Jews had a disproportinally high influence in the administration of the Communist Poland. In far-right politics, the antisemitic canards of "Jewish Bolshevism", "Jewish Communism", and the "Zionist Occupation Government" (ZOG) conspiracy theory are catchwords falsely asserting that Communism is a Jewish conspiracy.[6]

Origins

The conflation of Jews and revolution emerged in the atmosphere of destruction of Russia during World War I. When the revolutions of 1917 crippled Russia's war effort, conspiracy theories developed far from Berlin and Petrograd. Many Britons for example ascribed the Russian Revolution to an "apparent conjunction of Bolsheviks, Germans and Jews".[8] By December 1917, only five of the twenty-one members of the Communist Central Committee were Jews: the commissar for foreign affairs, the president of the Supreme Soviet, the deputy chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, the president of Petrograd Soviet, and the deputy director of the Cheka secret police.[9]

The worldwide spread of the concept in the 1920s is associated with the publication and circulation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fraudulent document that purported to describe a secret Jewish conspiracy aimed at world domination. The expression made an issue out of the Jewishness of some leading Bolsheviks (such as Leon Trotsky) during and after the October Revolution. Daniel Pipes said that "primarily through The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the Whites spread these charges to an international audience."[10] James Webb wrote that it is rare to find an antisemitic source after 1917 that "does not stand in debt to the White Russian analysis of the Revolution".[11]

Jewish involvement in Russian Communism

Antisemitism in the Russian Empire existed both culturally and institutionally. The Jews were restricted to live within the Pale of Settlement,[12] and suffered pogroms.[13][14]

As a result, many Jews supported gradual or revolutionary changes within the Russian Empire. Those movements ranged among the far left (Jewish Anarchism,[15] Bundists, Bolsheviks, Mensheviks,[16]) and moderate left (Trudoviks[17]) and constitutionalist (Constitutional Democrats[18]) parties. According to the 1922 Bolshevik party census, there were 19,564 Jewish Bolsheviks, comprising 5.21% of the total, and in the 1920s of the 417 members of the Central Executive Committee, the party Central Committee, the Presidium of the Executive of the Soviets of the USSR and the Russian Republic, the People's Commissars, 6% were ethnic Jews.[19] Between 1936 and 1940, during the Great Purge, Yezhovshchina and after the rapprochement with Nazi Germany, Stalin had largely eliminated Jews from senior party, government, diplomatic, security and military positions.[20]

Some scholars have grossly exaggerated Jewish presence in the Soviet Communist Party. For example, Alfred Jensen said that in the 1920s "75 per cent of the leading Bolsheviks" were "of Jewish origin". According to Aaronovitch, "a cursory examination of membership of the top committees shows this figure to be an absurd exaggeration".[21]

Nazi Germany

Walter Laqueur traces the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy theory to Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, for whom Bolshevism was "the revolt of the Jewish, Slavic and Mongolian races against the German (Aryan) element in Russia". Germans, according to Rosenberg, had been responsible for Russia's historic achievements and had been sidelined by the Bolsheviks, who did not represent the interests of the Russian people, but instead those of its ethnic Jewish and Chinese population.[22]

Michael Kellogg, in his Ph.D. thesis, argues that the racist ideology of Nazis was to a significant extent influenced by White émigrés in Germany, many of whom, while being former subjects of the Russian Empire, were of non-Russian descent: ethnic Germans, residents of Baltic lands including Baltic Germans, and Ukrainians. Of particular role was their Aufbau organization (Aufbau: Wirtschafts-politische Vereinigung für den Osten (Reconstruction: Economic-Political Organization for the East)). For example, its leader was instrumental in making The Protocols of The Elders of Zion available in German language. He argues that early Hitler was rather philosemitic, and became rabidly antisemitic since 1919 under the influence of the White émigré convictions about the conspiracy of the Jews, an unseen unity from financial capitalists to Bolsheviks, to conquer the world.[23] Therefore, his conclusion is that White émigrés were at the source of the Nazi concept of Jewish Bolshevism. Annemarie Sammartino argues that this view is contestable. While there is no doubt that White emigres were instrumental in reinforcing the idea of 'Jewish Bolshevism' among Nazis, the concept is also found in many German early post–World War I documents. Also, Germany had its own share of Jewish Communists "to provide fodder for the paranoid fantasies of German antisemites" without Russian Bolsheviks.[24]

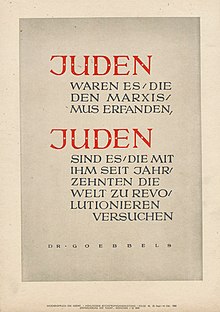

During the 1920s, Hitler declared that the mission of the Nazi movement was to destroy "Jewish Bolshevism".[25] Hitler asserted that the "three vices" of "Jewish Marxism" were democracy, pacifism and internationalism,[26] and that the Jews were behind Bolshevism, communism and Marxism.[27]

In Nazi Germany, this concept of Jewish Bolshevism reflected a common perception that Communism was a Jewish-inspired and Jewish-led movement seeking world domination from its origin. The term was popularized in print in German journalist Dietrich Eckhart's 1924 pamphlet "Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin" ("Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin") which depicted Moses and Lenin as both being Communists and Jews. This was followed by Alfred Rosenberg's 1923 edition of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Hitler's Mein Kampf in 1925, which saw Bolshevism as "Jewry's twentieth century effort to take world dominion unto itself".

According to French spymaster and writer Henri Rollin, "Hitlerism" was based on "anti-Soviet counter-revolution" promoting the "myth of a mysterious Jewish–Masonic–Bolshevik plot", entailing that the First World War had been instigated by a vast Jewish–Masonic conspiracy to topple the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian Empires and implement Bolshevism by fomenting liberal ideas.[28]

A major source for propaganda about Jewish Bolshevism in the 1930s and early 1940s was the pro-Nazi and antisemitic international Welt-Dienst news agency founded in 1933 by Ulrich Fleischhauer.

Within the German Army, a tendency to see Soviet Communism as a Jewish conspiracy had grown since the First World War, something that became officialized under the Nazis. A 1932 pamphlet by Ewald Banse of the Government-financed German National Association for the Military Sciences described the Soviet leadership as mostly Jewish, dominating an apathetic and mindless Russian population.[29]

Propaganda produced in 1935 by the psychological war laboratory of the German War Ministry described Soviet officials as "mostly filthy Jews" and called on Red Army soldiers to rise up and kill their "Jewish commissars". This material was not used at the time, but served as a basis for propaganda in the 1940s.[30]

Members of the SS were encouraged to fight against the "Jewish Bolshevik sub-humans". In the pamphlet The SS as an Anti-Bolshevist Fighting Organization, published in 1936, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler wrote:

We shall take care that never again in Germany, the heart of Europe, will the Jewish-Bolshevistic revolution of subhumans be able to be kindled either from within or through emissaries from without.[31]

In his speech to the Reichstag justifying Operation Barbarossa in 1941, Hitler said:

For more than two decades the Jewish Bolshevik regime in Moscow had tried to set fire not merely to Germany but to all of Europe ... The Jewish Bolshevik rulers in Moscow have unswervingly undertaken to force their domination upon us and the other European nations and that is not merely spiritually, but also in terms of military power ... Now the time has come to confront the plot of the Anglo-Saxon Jewish war-mongers and the equally Jewish rulers of the Bolshevik centre in Moscow![32]

Field-Marshal Wilhelm Keitel gave an order on 12 September 1941 which declared: "the struggle against Bolshevism demands ruthless and energetic, rigorous action above all against the Jews, the main carriers of Bolshevism".[33]

Historian Richard J. Evans wrote that Wehrmacht officers regarded the Russians as "sub-human", and were from the time of the invasion of Poland in 1939 telling their troops the war was caused by "Jewish vermin", explaining to the troops that the war against the Soviet Union was a war to wipe out what were variously described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans", the "Mongol hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "red beast", language clearly intended to produce war crimes by reducing the enemy to something less than human.[34]

Joseph Goebbels published an article in 1942 called "the so-called Russian soul" in which he claimed that Bolshevism was exploiting the Slavs and that the battle of the Soviet Union determined whether Europe would become under complete control by international Jewry.[35]

Nazi propaganda presented Barbarossa as an ideological-racial war between German National Socialism and "Judeo-Bolshevism", dehumanising the Soviet enemy as a force of Slavic Untermensch (sub-humans) and "Asiatic" savages engaging in "barbaric Asiatic fighting methods" commanded by evil Jewish commissars whom German troops were to grant no mercy.[36] The vast majority of the Wehrmacht officers and soldiers tended to regard the war in Nazi terms, seeing their Soviet opponents as sub-human.[37]

While National Socialism brought about a new version and formulation of European culture, Bolshevism is the declaration of war by Jewish-led international subhumans against culture itself. It is not only anti-bourgeois, but it is also anti-cultural. It means, in the final consequence, the absolute destruction of all economic, social, state, cultural, and civilizing advances made by western civilization for the benefit of a rootless and nomadic international clique of conspirators, who have found their representation in Jewry.

Outside Nazi Germany

Great Britain, 1920s

In the early 1920s, a leading British antisemite, Henry Hamilton Beamish, stated that Bolshevism was the same thing as Judaism.[39] In the same decade, future wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill penned an editorial entitled "Zionism versus Bolshevism", which was published in the Illustrated Sunday Herald. In the article, which asserted that Zionism and Bolshevism were engaged in a "struggle for the soul of the Jewish people", he called on Jews to repudiate "the Bolshevik conspiracy" and make clear that "the Bolshevik movement is not a Jewish movement" but stated that:

[Bolshevism] among the Jews is nothing new. From the days of Spartacus-Weishaupt to those of Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky (Russia), Bela Kun (Hungary), Rosa Luxemburg (Germany), and Emma Goldman (United States), this world-wide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilisation and for the reconstitution of society on the basis of arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality, has been steadily growing.[40]

Author Gisela C. Lebzelter noted that Churchill's analysis failed to analyze the role that Russian oppression of Jews had played in their joining various revolutionary movements, but instead "to inherent inclinations rooted in Jewish character and religion".[41]

Works propagating the Jewish Bolshevism canard

The Octopus

The Octopus is a 256-page book self-published in 1940 by Elizabeth Dilling under the pseudonym "Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson". In it she describes her theories of Jewish Bolshevism.[42]

Criticism of the Jewish Bolshevism canard

Researchers in the field, such as Polish philosopher Stanisław Krajewski[44] or André Gerrits,[45] denounce the concept of Jewish Bolshevism as a prejudice. Law professor Ilya Somin agrees, and compares Jewish involvement in other communist countries. "Overrepresentation of a group in a political movement does not prove either that the movement was 'dominated' by that group or that it primarily serves that group's interests. The idea that communist oppression was somehow Jewish in nature is belied by the record of communist regimes in countries like China, North Korea, and Cambodia, where the Jewish presence was and is minuscule."[46]

Several scholars have observed that Jewish involvement in Communist movements was primarily a response to antisemitism and rejection by established politics.[47][48][49] Others note that this involvement was greatly exaggerated to accord with existing antisemitic narratives.[50][51][52][53][54][55]

Philip Mendes observed this on a policy level:

The increasing Jewish involvement in political radicalism... left government authorities with a number of potential options for response. One option was to recognize the structural link between the oppression of the Jews and their involvement in the Left, and to introduce social and political reforms which ended discrimination against Jews... This option would have meant accepting that Jews had as much right as any other religious or ethnic grouping to freely participate in political activities. The second option... was to reject any social or political emancipation of Jews... Instead, this policy blamed the Jewish victims for their persecution, and assumed that anti-Semitic legislation and violence was justified as a response to the alleged threat of ‘Jewish Bolshevism’. In short, cause and effect were reversed, and Jewish responses to anti-Semitism were utilized to rationalize anti-Semitic practices.[49]

See also

Notes

- Alderman 1983.

- Partridge, Christopher; Geaves, Ron (2007). "Antisemitism, Conspiracy Culture, Christianity, and Islam: The History and Contemporary Religious Significance of the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion". In Lewis, James R.; Hammer, Olav (eds.). The Invention of Sacred Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–95. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511488450.005. ISBN 9780511488450. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Frederickson, Kari (1996). "Cathrine Curtis and Conservative Isolationist Women, 1939–1941". The Historian. 58 (4): 826. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1996.tb00977.x. ISSN 0018-2370.

- Glen Jeansonne (9 June 1997). Women of the Far Right: The Mothers' Movement and World War II. University of Chicago Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-226-39589-0. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- Laqueur, Walter Ze'ev (1965). Russia and Germany. Transaction Publishers. p. 105. ISBN 9781412833547. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Philip Mendes (2010). "Debunking the myth of Jewish communism". Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Serhii Plokhy (1 December 2015). The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. Basic Books. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-465-07394-8. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Fromkin (2009) pp. 247–248.

- Sachar, Howard (2006). A History of the Jews in the Modern World. Vintage. ISBN 9781400030972.

- Pipes 1997, p. 93.

- Webb 1976, p. 295.

- "Who could live outside the Pale of Settlement?". Jewish Family Search. 3 May 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Modern Jewish History: Pogroms". Jewish Virtual Library. Encyclopaedia Judaica (The Gale Group). 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Wein, Berel (1 September 1990). Triumph of Survival: The Story of the Jews in the Modern Era 1650–1990. Mesorah Publications. p. 173. ISBN 9780899064987. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Goncharok, Moshe (1996). "Vek voli. Russky anarkhizm I evreyi (XIX–XX vv.)" Век воли. Русский анархизм и евреи (XIX–XX вв.) [Century of Will: Russian Anarchism and the Jews (19th–20th centuries)] (in Russian). Jerusalem: Mishmeret Shalom. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- Levin 1988, p. 13.

- Ascher 1992, p. 148.

- Witte 1907.

- Herf 2008, p. 96.

- Levin 1988, pp. 318–325.

- Aaronovitch, David (23 September 2011). "Our Jewish Communist past". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Laqueur 1990, pp. 33–34.

- Kellogg, Michael (2005). The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Émigrés and the Making of National Socialism, 1917–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84512-0.

- Sammartino, Annemarie (September 2006). "Michael Kellogg: The Russian Roots of Nazism (review)". Humanities and Social Sciences Net. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Kershaw 1999, p. 257.

- Kershaw 1999, p. 303.

- Kershaw 1999, p. 259.

- Kellogg 2008.

- Förster 2005, p. 119.

- Förster 2005, pp. 122–127.

- Himmler 1936, p. 8.

- Hillgruber 1987.

- Kershaw 2000, p. 465.

- Evans 1989, pp. 59–60.

- Goebbels, Joseph (1943). "Die sogenannte russische Seele" [The So-Called Russian Soul]. Das eherne Herz [The iron heart]. Translated by Bytwerk, Randall. Munich: Zentralverlag der NSDAP. pp. 398–405. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013 – via German Propaganda Archive at Calvin University.

- Förster 2005, p. 126.

- Förster 2005, p. 127.

- "Goebbels Claims Jews Will Destroy Culture". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. September 1935. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Webb 1976, p. 130.

- Churchill 1920.

- Lebzelter 1978, p. 181.

- Glen Jeansonne (9 June 1997). Women of the Far Right: The Mothers' Movement and World War II. University of Chicago Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-226-39589-0. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- Primary Source Microfilm 2005.

- Krajewski, Stanislaw (October 2007). "Jews, Communists and Jewish Communists, in Poland, Europe and Beyond". Covenant. 1 (3). Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019. Originally in a CEU annual Jewish Studies at the Central European University, ed. by Andras Kovacs, co-editor Eszter Andor, CEU 2000, 119–133

- Gerrits 2009, p. 195.

- Somin, Ilya (29 October 2011). "Communism and the Jews". The Volokh Conspiracy. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Jaff Schatz, The Generation: The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Communists of Poland, University of California Press, 1991, p. 95.

- Jaff Schatz, "Jews and the Communist Movement in Interwar Poland," in Jonathan Frankel, Dark Times, Dire Decisions: Jews and Communism: Studies in Contemporary Jewry Archived 1 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University Press US, 2005, p. 30.

- Mendes, Philip (2014). Jews and the left : the rise and fall of a political alliance. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-00829-9. OCLC 865063358.

- Niall Ferguson, The War of the World, The Penguin Press, New York 2006, page 422

- Antony Polonsky, Poles, Jews and the Problems of a Divided Memory Archived 17 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, page: 20 (PDF file: 208 KB)

- Andre Gerrits. "Antisemitism and Anti-Communism: The Myth of 'Jiudeo-Communism' in Eastern Europe". East European Jewish Affairs. 1995, Vol. 25, No. 1:49–72. Page 71.

- Magdalena Opalski, Israel Bartal. Poles and Jews: A Failed Brotherhood. Archived 8 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine University Press of New England, 1992. P29-30

- Joanna B. Michlic. Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present. Archived 9 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine University of Nebraska Press, 2006. Pages 47–48.

- Ezra Mendelsohn, Studies in Contemporary Jewry, Oxford University Press US, 2004, ISBN 0-19-517087-3, Google Print, p.279 Archived 6 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Alderman, G. (1983). The Jewish Community in British Politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ascher, Abraham (1992). The Revolution of 1905. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Churchill, Winston (8 February 1920). "Zionism versus Bolshevism". Illustrated Sunday Herald.

- Evans, Richard J. (1989). In Hitler's Shadow West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape the Nazi Past. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 978-0-394-57686-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Figes, Orlando (2008). The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia. London: Picador.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Förster, Jürgen (2005). "The German Military's Image of Russia". In Erickson, Ljubica; Erickson, Mark (eds.). Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Isaiah (1997). Germany, Turkey, and Zionism 1897-1918. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0765804075

- Fromkin, David (2009). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0805088090

- Gerrits, André (2009). The Myth of Jewish Communism: A Historical Interpretation. Peter Lang.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herf, Jeffrey (2008). The Jewish Enemy: Nazi Propaganda During World War II and the Holocaust. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hillgruber, Andreas (1987). "War in the East and the Extermination of the Jews" (PDF). 18. Yad Vashem Studies: 103–132. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Himmler, Heinrich (1936). Die Schutzstaffel als Antibolschewistische Kampforganisation (in German). Franz Eher Verlag. External link in

|title=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Hoffman, Stefani; Mendelsohn, Ezra (2008). The Revolution of 1905 and Russia's Jews. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kellogg, Michael (2008). The Russian Roots of Nazism. White Émigrés and the Making of National Socialism, 1917–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521070058.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (1999). Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-192579-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (2000). Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-027239-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laqueur, Walter (1990). Russia and Germany: A Century of Conflict. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lebzelter, Gisela (1978). Political anti-Semitism in England: 1918-1939. Oxford: Macmillan. ISBN 9780333242513.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levin, Nora (1988). The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917. New York University Press: New York.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McMeekin, Sean (2012). The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany's Bid for World Power. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674064324

- Moss, Walter (2005). A History of Russia: Since 1855. Anthem Press. ISBN 1-84331-034-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pinkus, Benjamin (1990). The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pipes, Daniel (1997). Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where it Comes From. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83131-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Radicalism and Reactionary Politics in America". The Hall-Hoag Collection of Dissenting and Extremist Printed Propaganda. Woodbridge: Primary Source Microfilm. 2005.

- Resis, Albert (2000). "The Fall of Litvinov: Harbinger of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact". Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (1): 33–56. doi:10.1080/09668130098253. JSTOR 153750.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ro'i, Yaacov (1995). Jews and Jewish Life in Russia and the Soviet Union. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4619-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webb, James (1976). Occult Establishment: The Dawn of the New Age and the Occult Establishment. Open Court Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wein, Berel (1976). Triumph of Survival: The Jews in the Modern Era 1600-1990. Brooklyn: Mesorah.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Witte, Sophie (24 March 1907). "Just Before the Duma Opened" (PDF). New York Times.

Further reading

- Mikhail Agursky: The Third Rome: National Bolshevism in the USSR, Boulder: Westview Press, 1987 ISBN 0-8133-0139-4

- Harry Defries, Conservative Party Attitudes to Jews, 1900-1950 Jewish Bolshevism, p. 70, ISBN 0-7146-5221-0

- Fay, Brendan (26 July 2019). "The Nazi Conspiracy Theory: German Fantasies and Jewish Power in the Third Reich". Library & Information History. 35 (2): 75–97. doi:10.1080/17583489.2019.1632574.

- Johannes Rogalla von Bieberstein: '"Juedischer Bolschewismus". Mythos und Realität'. Dresden: Antaios, 2003, ISBN 3-935063-14-8; 2.ed. Graz: Ares, 2010.

- Peter Longerich: Holocaust - The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews OUP 2010 ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Muller, Jerry Z. (2010). "Radical Anticapitalism: the Jew as Communist". Capitalism and the Jews. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3436-5.

- Yuri Slezkine: The Jewish Century, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004 ISBN 0-691-11995-3

- Scott Ury, Barricades and Banners: The Revolution of 1905 and the Transformation of Warsaw Jewry (Stanford, 2012). ISBN 978-0-804763-83-7

- Arkady Vaksberg: Stalin against the Jews, New York: Vintage Books (a division of Random House), 1994, ISBN 0-679-42207-2

- Robert Wistrich: Revolutionary Jews from Marx to Trotsky, London: Harrap, 1976 ISBN 0-245-52785-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jewish Bolshevism. |