Augusta, Lady Gregory

Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (née Persse; 15 March 1852 – 22 May 1932)[1] was an Irish dramatist, folklorist and theatre manager. With William Butler Yeats and Edward Martyn, she co-founded the Irish Literary Theatre and the Abbey Theatre, and wrote numerous short works for both companies. Lady Gregory produced a number of books of retellings of stories taken from Irish mythology. Born into a class that identified closely with British rule, she turned against it. Her conversion to cultural nationalism, as evidenced by her writings, was emblematic of many of the political struggles to occur in Ireland during her lifetime.

Augusta, Lady Gregory | |

|---|---|

Lady Gregory pictured on the frontispiece to "Our Irish Theatre: A Chapter of Autobiography" (1913) | |

| Born | Isabella Augusta Persse 15 March 1852 Roxborough, County Galway, Ireland |

| Died | 22 May 1932 (aged 80) |

| Resting place | New Cemetery in Bohermore, County Galway, Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Dramatist, folklorist, theatre manager |

Notable work | Irish Literary Revival |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | William Robert Gregory |

| Relatives | Sir Hugh Lane (nephew) |

Lady Gregory is mainly remembered for her work behind the Irish Literary Revival. Her home at Coole Park in County Galway served as an important meeting place for leading Revival figures, and her early work as a member of the board of the Abbey was at least as important as her creative writings for that theatre's development. Lady Gregory's motto was taken from Aristotle: "To think like a wise man, but to express oneself like the common people."[2]

Biography

Early life and marriage

Gregory was born at Roxborough, County Galway, the youngest daughter of the Anglo-Irish gentry family Persse. Her mother, Frances Barry, was related to Viscount Guillamore, and her family home, Roxborough, was a 6,000-acre (24 km²) estate located between Gort and Loughrea, the main house of which was later burnt down during the Irish Civil War.[3] She was educated at home, and her future career was strongly influenced by the family nurse (i.e. nanny), Mary Sheridan, a Catholic and a native Irish speaker, who introduced the young Augusta to the history and legends of the local area.[4]

She married Sir William Henry Gregory, a widower with an estate at Coole Park, near Gort, on 4 March 1880 in St Matthias' Church, Dublin.[5] Sir William, who was 35 years her elder, had just retired from his position as Governor of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), having previously served several terms as Member of Parliament for County Galway. He was a well-educated man with many literary and artistic interests, and the house at Coole Park housed a large library and extensive art collection, both of which Lady Gregory was eager to explore. He also had a house in London, where the couple spent a considerable amount of time, holding weekly salons frequented by many leading literary and artistic figures of the day, including Robert Browning, Lord Tennyson, John Everett Millais and Henry James. Their only child, Robert Gregory, was born in 1881. He was killed during the First World War while serving as a pilot, an event which inspired W. B. Yeats's poems "An Irish Airman Foresees His Death", "In Memory of Major Robert Gregory" and "Shepherd and Goatherd".[6][7]

Early writings

The Gregorys travelled in Ceylon, India, Spain, Italy and Egypt. While in Egypt, Lady Gregory had an affair with the English poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, during which she wrote a series of love poems, A Woman's Sonnets.[8][9]

Her earliest work to appear under her own name was Arabi and His Household (1882), a pamphlet—originally a letter to The Times—in support of Ahmed Orabi Pasha, leader of what has come to be known as the Urabi Revolt, an 1879 Egyptian nationalist revolt against the oppressive regime of the Khedive and the European domination of Egypt. She later said of this booklet, "whatever political indignation or energy was born with me may have run its course in that Egyptian year and worn itself out".[10] Despite this, in 1893 she published A Phantom's Pilgrimage, or Home Ruin, an anti-Nationalist pamphlet against William Ewart Gladstone's proposed second Home Rule Act.[11]

She continued to write prose during the period of her marriage. During the winter of 1883, whilst her husband was in Ceylon, she worked on a series of memoirs of her childhood home, with a view to publishing them under the title An Emigrant's Notebook,[12] but this plan was abandoned. She wrote a series of pamphlets in 1887 called Over the River, in which she appealed for funds for the parish of St. Stephens in Southwark, south London.[13] She also wrote a number of short stories in the years 1890 and 1891, although these also never appeared in print. A number of unpublished poems from this period have also survived. When Sir William Gregory died in March 1892, Lady Gregory went into mourning and returned to Coole Park; there she edited her husband's autobiography, which she published in 1894.[14] She was to write later, "If I had not married I should not have learned the quick enrichment of sentences that one gets in conversation; had I not been widowed I should not have found the detachment of mind, the leisure for observation necessary to give insight into character, to express and interpret it. Loneliness made me rich—'full', as Bacon says.".[15]

Cultural nationalism

A trip to Inisheer in the Aran Islands in 1893 re-awoke for Lady Gregory an interest in the Irish language[16] and in the folklore of the area in which she lived. She organised Irish lessons at the school at Coole, and began collecting tales from the area around her home, especially from the residents of Gort workhouse. One of the tutors she employed was Norma Borthwick, who would visit Coole numerous times.[17] This activity led to the publication of a number of volumes of folk material, including A Book of Saints and Wonders (1906), The Kiltartan History Book (1909) and The Kiltartan Wonder Book (1910). She also produced a number of collections of "Kiltartanese" versions of Irish myths, including Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902) and Gods and Fighting Men (1903). ("Kiltartanese" is Lady Gregory's term for English with Gaelic syntax, based on the dialect spoken in Kiltartan.) In his introduction to the former, Yeats wrote "I think this book is the best that has come out of Ireland in my time.".[18] James Joyce was to parody this claim in the Scylla and Charybdis chapter of his novel Ulysses.[19]

Towards the end of 1894, encouraged by the positive reception of the editing of her husband's autobiography, Lady Gregory turned her attention to another editorial project. She decided to prepare selections from Sir William Gregory's grandfather's correspondence for publication as Mr Gregory's Letter-Box 1813–30 (1898). This entailed her researching Irish history of the period; one outcome of this work was a shift in her political position, from the "soft" Unionism of her earlier writing on Home Rule to a definite support of Irish nationalism and Republicanism, and to what she was later to describe as "a dislike and distrust of England".[20]

Founding of the Abbey

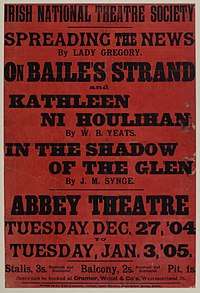

Edward Martyn was a neighbour of Lady Gregory, and it was during a visit to his home, Tullira Castle, in 1896 that she first met W. B. Yeats.[21] Discussions between the three of them, over the following year or so, led to the founding of the Irish Literary Theatre in 1899.[22] Lady Gregory undertook fundraising, and the first programme consisted of Martyn's The Heather Field and Yeats's The Countess Cathleen.

The Irish Literary Theatre project lasted until 1901,[23] when it collapsed owing to lack of funding. In 1904, Lady Gregory, Martyn, Yeats, John Millington Synge, Æ, Annie Horniman and William and Frank Fay came together to form the Irish National Theatre Society. The first performances staged by the society took place in a building called the Molesworth Hall. When the Hibernian Theatre of Varieties in Lower Abbey Street and an adjacent building in Marlborough Street became available, Horniman and William Fay agreed to their purchase and refitting to meet the needs of the society.[24]

On 11 May 1904, the society formally accepted Horniman's offer of the use of the building. As Horniman was not normally resident in Ireland, the Royal Letters Patent required were paid for by her but granted in the name of Lady Gregory.[25] One of her own plays, Spreading the News, was performed on the opening night, 27 December 1904.[26] At the opening of Synge's The Playboy of the Western World in January 1907, a significant portion of the crowd rioted, causing the remainder of the performances to be acted out in dumbshow.[27] Lady Gregory did not think as highly of the play as Yeats did, but she defended Synge as a matter of principle. Her view of the affair is summed up in a letter to Yeats where she wrote of the riots: "It is the old battle, between those who use a toothbrush and those who don't."[28]

Later career

Lady Gregory remained an active director of the theatre until ill-health led to her retirement in 1928. During this time she wrote more than 19 plays, mainly for production at the Abbey.[16] Many of these were written in an attempted transliteration of the Hiberno-English dialect spoken around Coole Park that became widely known as Kiltartanese, from the nearby village of Kiltartan. Her plays had been among the most successful at the Abbey in the earlier years,[29] but their popularity declined. Indeed, the Irish writer Oliver St. John Gogarty once wrote "the perpetual presentation of her plays nearly ruined the Abbey".[30] In addition to her plays, she wrote a two-volume study of the folklore of her native area called Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland in 1920. She also played the lead role in three performances of Cathleen Ni Houlihan in 1919.

During her time on the board of the Abbey, Coole Park remained her home; she spent her time in Dublin staying in a number of hotels. For example, at the time of the 1911 national census, she was staying in a hotel at 16 South Frederick Street.[31] In these she dined frugally, often on food she had brought with her from home. She frequently used her hotel rooms to interview would-be Abbey dramatists and to entertain the company after opening nights of new plays. She spent many of her days working on her translations in the National Library of Ireland. She gained a reputation as being a somewhat conservative figure.[32] For example, when Denis Johnston submitted to the Abbey his first play, Shadowdance, it was rejected by Lady Gregory and returned to the author with "The Old Lady says No" written on the title page.[33] Johnston decided to rename the play, and The Old Lady Says 'No!' was eventually staged by the Gate Theatre in 1928.

Retirement and death

When she retired from the Abbey board, Lady Gregory returned to live in Galway, although she continued to visit Dublin regularly. The house and demesne at Coole Park had been sold to the Irish Forestry Commission in 1927, with Lady Gregory retaining life tenancy.[34] Her Galway home had long been a focal point for the writers associated with the Irish Literary Revival, and this continued after her retirement. On a tree in what were the grounds of the house, one can still see the carved initials of Synge, Æ, Yeats and his artist brother Jack, George Moore, Seán O'Casey, George Bernard Shaw, Katharine Tynan and Violet Martin. Yeats wrote five poems about, or set in, the house and grounds: "The Wild Swans at Coole", "I walked among the seven woods of Coole", "In the Seven Woods", "Coole Park, 1929" and "Coole Park and Ballylee, 1931".

Lady Gregory, whom Shaw once described as "the greatest living Irishwoman",[35] died at home aged 80 from breast cancer,[14] and is buried in the New Cemetery in Bohermore, County Galway. The entire contents of Coole Park were auctioned three months after her death, and the house was demolished in 1941.[36]

Legacy

Her plays fell out of favour after her death, and are now rarely performed.[37] Many of the diaries and journals she kept for most of her adult life have been published, providing a rich source of information on Irish literary history during the first three decades of the 20th century.[38]

Her Cuchulain of Muirthemne is still considered a good retelling of the Ulster Cycle tales such as Deidre, Cuchulainn, and the Táin Bó Cúailnge stories. Thomas Kinsella wrote "I emerged with the conviction that Lady Gregory's 'Cuchulian of Muirthemne', though only a paraphrase, gave the best idea of the Ulster stories".[39] However her version omitted some elements of the tale, usually assumed to avoid offending Victorian sensibilities, as well being an attempt as presenting a 'respectable' nation myth for the Irish, though her paraphrase is not considered dishonest.[40] Other critics find the bowdlerisations in her works more offensive, not only the removal of references to sex and bodily functions, but also the loss of Cuchulain's "battle frenzy" (Ríastrad); in other areas she censored less than some of her male contemporaries, such as Standish O'Grady.[41]

Published works

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1882), Arabi and his household

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1888), Over the River

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1893), A Phantom's Pilgrimage, or Home Ruin (anonymously)

- Lady Gregory, Augusta, ed. (1894), Sir William Gregory, K.C.M.G., formerly member of Parliament and sometime governor of Ceylon : an autobiography (2nd ed.)

- Lady Gregory, Augusta, ed. (1898), Mr. Gregory's Letter Box 1813–1830

- Douglas, Hyde (1902), Casadh an t-súgáin; or, The twisting of the rope (in Irish and English), translated by Lady Gregory, Augusta

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1903) [1902], Cuchulain of Muirthemne : the story of the men of the Red Branch of Ulster (2nd ed.)

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1903), Poets and Dreamers : Studies and Translations from the Irish by Lady Gregory

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1904), Gods and Fighting Men : The Story of the Tuatha de Danann and of the Fianna of Ireland

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1905), Kincora : a drama in three acts

- Lady Gregory, Augusta; Hyde, Douglas (1906), Spreading the New, The Rising of the Moon. By Lady Gregory. The Poorhouse. By Lady Gregory and Douglas Hyde

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1906), The Hyacinth Galvey ; a comedy

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1907), A Book of Saints and Wonders put down here by Lady Gregory according to the Old Writings and the Memory of the People of Ireland

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1909), Seven Short Plays: Spreading the News. Hyacinth Halvey. The Rising of the Moon. The Jackdaw. The Workhouse Ward. The Travelling Man. The Gaol Gate

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1926) [1909], The Kiltartan History Book, illustrated by Robert Gregory (Second, enlarged ed.)

- Molière (1910), The Kiltartan Molière: The Miser. The Doctor in spite of himself. The Roqueries of Scapin, translated by Lady Gregory, Augusta

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1911), Spreading the news

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1911), The Kiltartan Wonder Book by Lady Gregory, illustrated by Margaret Gregory

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1912), Irish Folk-History Plays, 1st series. The Tragedies : Grania – Kincora – Dervorgilla

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1912), Irish Folk-History Plays, 2nd series: The Tragic-Comedies : The Canavans – The White Cockade – The Deliverer

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1913), New Comedies : The Bogie Men ; The Full Moon ; Coats ; Damer's Gold ; McDonough's Wife

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1913), Damer's Gold : a comedy in two acts

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1913), Coats

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1913), Our Irish Theatre – A Chapter of Autobiography

- Yeats, W.B.; Lady Gregory, Augusta (1915), The unicorn from the stars : and other plays

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1916), The Golden Apple; a play for Kiltartan children

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1919), The Kiltartan Poetry Book; prose translations from the Irish

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1915), Shanwalla

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1920), The Dragon : A wonder play in three acts

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1920), Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland collected and arranged by Lady Gregory : With two essays and notes by W.B. Yeats

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1921), Hugh Lane's life and achievement, with some account of the Dublin galleries. With illustrations

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1922), The Image and Other Plays also : Hanranhan's Ghost ; Shanwalla ; The Wrens

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1922), Three Wonder Plays. The Dragon. Aristotle's Bellows. The Jester

- Yeats, W.B.; Lady Gregory, Augusta (1922), Plays in prose and verse : written for an Irish theatre, and generally with the help of a friend

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1924), The Story Brought by Brigit

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1924), Mirandolina

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1926), On the Racecourse

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1928), Three Last Plays: Sancho's Master. Dave. The Would-be Gentleman

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1930), My First Play (Colman and Guaire)

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1931), Coole

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1947), Robinson, Lennox (ed.), Lady Gregory's Journals

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1974), Smythe, Colin (ed.), Seventy Years, 1852-1922, being the autobiography of Lady Gregory

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1978), Murphy, Daniel J. (ed.), The Journals. Part 1. 10 October 1916 – 24 February 1925

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1987), Murphy, Daniel J. (ed.), The Journals. Part 2. 21 February 1925 – 9 May 1932

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (1996), Pethica, James (ed.), Lady Gregory's Diaries 1892-1902

- Lady Gregory, Augusta (2018), Pethica, James (ed.), Lady Gregory's Early Irish Writings 1883-1893

See also

- Cathleen Ní Houlihan

References

- "Augusta, Lady Gregory". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Yeats 2002, p. 391.

- Foster 2003, p. 484.

- Shrank & Demastes 1997, p. 108.

- Coxhead 1961, p. 22.

- "Representing the Great War: Texts and Contexts", The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 8th edition, accessed 5 October 2007.

- Kermode 1957, p. 31.

- Hennessy 2005.

- Holmes 2005, p. 103.

- Gregory 1976, p. 54.

- Kirkpatrick 2000, p. 109.

- Garrigan Mattar 2004, p. 187.

- Yeats 2005, p. 165, fn 2.

- Gonzalez 1997, p. 98.

- Owens & Radner 1990, p. 12.

- Lady Gregory". Irish Writers Online, accessed 23 September 2007.

- Rouse, Paul (2009). "Borthwick, Mariella Norma". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Love, Damian (2007), "Sailing to Ithaca: Remaking Yeats in Ulysses", The Cambridge Quarterly, 36 (1): 1–10, doi:10.1093/camqtly/bfl029

- Emerson Rogers 1948, pp. 306–327.

- Komesu & Sekine 1990, p. 102.

- Graham, Rigby (1972), "Letter from Dublin", American Notes & Queries, 10

- Foster 2003, pp. 486, 662.

- Kavanagh 1950.

- McCormack 1999, pp. 5–6.

- Yeats 2005, p. 902.

- Murray 2008.

- Ellis 2003.

- Frazier 2002.

- Pethica 2004.

- Augusta Gregory. Ricorso

- 1911 Census Form

- DiBattista & McDiarmid 1996, p. 216.

- Dick, Ellmann & Kiberd 1992, p. 183.

- Genet 1991, p. 271.

- Goldsmith 1854, p. 178.

- "Brief History of Coole Park" Archived 15 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Department of Arts, Heritage and the GAeltacht, accessed 6 April 2013.

- Gordon 1970, p. 28.

- Pethica 1995.

- Kinsella, Thomas (2002) [1969], The Tain, Translator's Note and Acknowledgements, p.vii

- Golightly, Karen B. (Spring 2007), "Lady Gregory's Deirdre: Self-Censorship or Skilled Editing?", New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, 11 (1): 117–126, JSTOR 20558141

- Maume, Patrick (2009), McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.), "Gregory, (Isabella) Augusta Lady Gregory Persse", Dictionary of Irish Biography, Cambridge University Press

Sources

- Coxhead, Elizabeth (1961), Lady Gregory: a literary portrait, Harcourt, Brace & World

- DiBattista, Maria; McDiarmid, Lucy (1996), High and Low Moderns: Literature and Culture, 1889–1939, New York: Oxford University Press

- Dick, Susan; Ellmann, Richard; Kiberd, Declan (1992), "Essays for Richard Ellmann: Omnium Gatherum", The Yearbook of English Studies, McGill-Queen's Press, 22 Medieval Narrative Special Number

- Ellis, Samantha (16 April 2003), "The Playboy of the Western World, Dublin, 1907", The Guardian

- Emerson Rogers, Howard (December 1948), "Irish Myth and the Plot of Ulysses", ELH, 15 (4): 306–327, doi:10.2307/2871620, JSTOR 2871620

- Foster, R. F (2003), W. B. Yeats: A Life, Vol. II: The Arch-Poet 1915–1939, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-818465-4

- Frazier, Adrian (23 March 2002), "The double life of a lady", The Irish Times

- Garrigan Mattar, Sinéad (2004), Primitivism, Science, and the Irish Revival, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926895-9

- Genet, Jacqueline (1991), The Big House in Ireland: Reality and Representation, Barnes & Noble

- Goldsmith, Oliver (1854), The Works of Oliver Goldsmith, London: John Murray, OCLC 2180329

- Gonzalez, Alexander G (1997), Modern Irish Writers: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook, Greenwood Press

- Gordon, Donald James (1970), W. B. Yeats: images of a poet: my permanent or impermanent images, Manchester University Press ND

- Graham, Rigby. "Letter from Dublin" (1972), American Notes & Queries, Vol. 10

- Gregory, Augusta (1976), Seventy years: being the autobiography of Lady Gregory, Macmillan

- Hennessy, Caroline (30 December 2005), "Lady Gregory: An Irish Life by Judith Hill", Raidió Teilifís Éireann

- Holmes, John (2005), Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Late Victorian Sonnet Sequence, Aldershot: Ashgate

- Igoe, Vivien (1994), A Literary Guide to Dublin, Methuen, ISBN 0-413-69120-9

- Kavanagh, Peter (1950), The Story of the Abbey Theatre: From Its Origins in 1899 to the Present, New York: Devin-Adair

- Kermode, Frank (1957), Romantic Image, New York: Vintage Books

- Kirkpatrick, Kathryn (2000), Border Crossings: Irish Women Writers and National Identities, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press

- Komesu, Okifumi; Sekine, Masuru (1990), Irish Writers and Politics, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-389-20926-0

- Love, Damian (2007), "Sailing to Ithaca: Remaking Yeats in Ulysses", The Cambridge Quarterly, 36 (1): 1–10, doi:10.1093/camqtly/bfl029

- McCormack, William (1999), The Blackwell Companion to Modern Irish Culture, Oxford: Blackwell

- Murray, Christopher, "Introduction to the abbeyonehundred Special Lecture Series" (PDF), abbeytheatre.ie, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2008

- Owens, Cóilín; Radner, Joan Newlon (1990), Irish Drama, 1900–1980, CUA Press

- Pethica, James (1995), Lady Gregory's Diaries 1892–1902, Colin Smythe, ISBN 0-86140-306-1

- Pethica, James L. (2004), "Gregory, (Isabella) Augusta, Lady Gregory (1852–1932)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press

- Ryan, Philip B (1998), The Lost Theatres of Dublin, The Badger Press, ISBN 0-9526076-1-1

- Shrank, Bernice; Demastes, William (1997), Irish playwrights, 1880–1995, Westport: Greenwood Press

- Tuohy, Frank (1991), Yeats, London: Herbert

- Yeats, William Butler (2002) [1993], Writings on Irish Folklore, Legend and Myth, Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-018001-X

- Yeats, William Butler (2005), Kelly, John; Schuchard, Richard (eds.), The collected letters of W. B. Yeats, Oxford University Press

- Brief History of Coole Park, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, archived from the original on 15 April 2013, retrieved 6 April 2013

- Representing the Great War: Texts and Contexts (8th ed.), The Norton Anthology of English Literature

Further reading

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Augusta, Lady Gregory |

- Kohfeldt, Mary Lou (1984), Lady Gregory: The Woman Behind the Irish Renaissance, André Deutsch, ISBN 0-689-11486-9

- McDiarmid, Lucy; Waters, Maureen (1996), "Lady Gregory: Selected Writings", Penguin Twentieth Century Classics, ISBN 0-14-018955-6

- Napier, Taura (February 2001), Seeking a Country: Literary Autobiographies of Irish Women". University Press of America, 2001;, ISBN 0-7618-1934-7

- Lady Gregory at Irish Writers Online, archived from the original on 19 November 2004, retrieved 4 November 2004

- Boland, Eavan, ed. (2007), Irish Writers on Writing featuring Augusta, Lady Gregory, Trinity University Press

- Plays Produced by the Abbey Theatre Co. and its Predecessors, with dates of First Performances, retrieved 4 November 2004

External links

| Library resources about Augusta, Lady Gregory |

| By Augusta, Lady Gregory |

|---|

- Works by Lady Gregory at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Lady Augusta Gregory at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Lady Gregory at Internet Archive

- Works by Augusta, Lady Gregory at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Archival material relating to Augusta, Lady Gregory". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Lady Gregory at Library of Congress Authorities, with 108 catalogue records

- Archival Material at Leeds University Library

- . . Dublin: Alexander Thom and Son Ltd. 1923. pp. – via Wikisource.