Jacksonville Beach, Florida

Jacksonville Beach is a coastal resort city in Duval County, Florida, United States. It was incorporated on May 22, 1907, as Pablo Beach, and would later change its name to Jacksonville Beach in 1925.[1] The city is part of group of communities collectively referred to as the Jacksonville Beaches. These communities include Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and Ponte Vedra Beach. When the city of Jacksonville consolidated with Duval County in 1968, Jacksonville Beach, together with Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and Baldwin, voted to retain their own municipal governments. As a result, citizens of Jacksonville Beach are also eligible to vote in mayoral election for the City of Jacksonville. As of the 2010 census, Jacksonville Beach had a total population of 21,362.[6]

Jacksonville Beach, Florida | |

|---|---|

| City of Jacksonville Beach | |

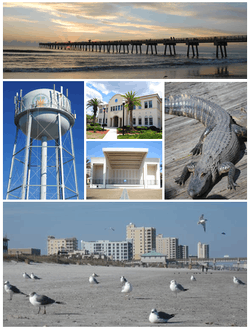

Images from top, left to right: Jacksonville Beach Pier, water tower, Jacksonville Beach City Hall, Sea Walk Pavilion, Adventure Landing, Jacksonville Beach | |

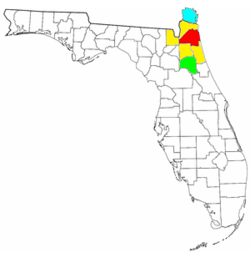

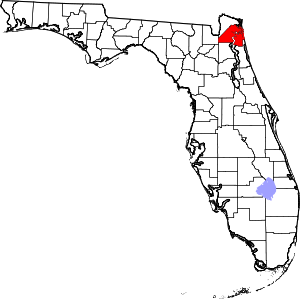

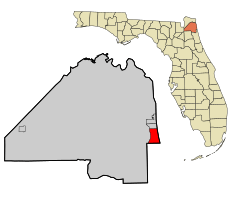

Location in Duval County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 30°17′3″N 81°23′46″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Duval |

| Settled | 1831[1] |

| Incorporated | May 22, 1907 (Pablo Beach)[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Charlie Latham |

| Area | |

| • City | 21.96 sq mi (56.89 km2) |

| • Land | 7.32 sq mi (18.95 km2) |

| • Water | 14.65 sq mi (37.93 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 21,362 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 23,628 |

| • Density | 3,228.75/sq mi (1,246.70/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,394,624 (US: 40th) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 32240, 32250 |

| Area code(s) | 904 |

| FIPS code | 12-35050 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0284697[5] |

| Website | City of Jacksonville Beach |

History

The area around present-day Jacksonville Beach was first settled by Spanish settlers. Spanish missions were established from Mayport to St. Augustine. Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain by treaty in 1763, only to have Spain regain it again, and then a final time in 1821 to the United States. American river pilots and fishermen came to Hazard, present-day Mayport, and established a port.[7]

Pablo Beach

In the late 19th century, developers began to see the potential in Duval County's oceanfront as a resort. In 1883 a group of investors formed the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad with the intention of developing a resort community that would be connected to Jacksonville by rail. The first settlers were William Edward Scull, a civil engineer and surveyor, and his wife Eleanor Kennedy Scull. They lived in a tent two blocks east of Pablo Historical Park. A second tent was the general store and post office. On August 22, 1884, Mrs. Scull was appointed postmaster. Mail was dispatched by horse and buggy up the beach to Mayport, and from there to Jacksonville by steamer. The Sculls built the first house in 1884 on their tent site. The settlement was named Ruby for their first daughter. On May 13, 1886, the town was renamed Pablo Beach after the San Pablo River.[8] In 1885, the San Pablo Diego Beach Land Co. sold town lots ranging from $50 to $100 each along with 5 to 10 acres (2.0 to 4.0 ha) lots from $10 to $20 per acre within 3 miles (4.8 km) of the new seaside resort "Pablo Beach".[9] In September 1892, work on the wagon road to Pablo Beach (Atlantic Boulevard) was begun.[10] The first resort hotel called the Murray Hall Hotel was established in mid 1886 but on August 7, 1890 it was destroyed in a fire.[11] By 1900 the railway company began to have financial difficulties and Henry Flagler took over as part of his Florida East Coast Railway. In late 1900 the railway was changed to standard gauge and was extended to Mayport.

The Spanish–American War broke out in 1898. The 3rd Nebraska arrived July 22, 1898, for training and embarkation. They encamped at Pablo Beach. They were led by three-time presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan.[12] After flooding in the camp at Pablo Beach the 3rd Nebraska moved to downtown Jacksonville.[13]

Jacksonville Beach

The amusement park phase of Jacksonville Beach began in 1905 with The Pavilion which was later expanded and called Little Coney Island. It was a popular tourist attraction that had such entertainment as a dance floor, swim room, bowling alley, and roller skate rinks. An issue with contracting, and constant weathering of its wooden structure aged Little Coney Island, causing it to be torn down in 1925. On June 15, 1925, the name Pablo Beach was changed to Jacksonville Beach.[8] The Shad's Pier was created in 1922 by Charles Shad and with help by Martin Williams. Around the same time W. H. Adams, Sr. created the Ocean View Pavilion amusement park on the former site of the Murray Hall Hotel. Adams wanted to create a larger roller coaster than the one at Little Coney Island. His vision resulted in a 93-feet high coaster. The location of the coaster by the beach made it vulnerable to damage and was eventually deemed unsafe. The coaster was then deconstructed to a smaller coaster. The deconstruction of the larger coaster hurt business at the amusement park. By 1949 the Ocean View Pavilion was in decline and then a fire destroyed it a few years later. The only amusement park in Jacksonville Beach today is Adventure Landing. The boardwalk declined in the 1950s due to the crackdown on gambling and games of chance. Driving on the beach was prohibited in 1979.[14]

Pablo Beach made aviation history on February 24, 1921, Lt. Wm. DeVoe Coney, in a transcontinental flight from San Diego, California, landed at Pablo Beach, having made the flight in 22 hours and 17 minutes, beating the old record, set two years earlier, by 3 hours and 32 minutes.[10] Coney's record was soon eclipsed on September 5, 1922, by Jimmy Doolittle piloting a De Havilland DH-4 biplane from Pablo Beach to San Diego in an elapsed time of 21 hours and 19 minutes.[15]

In 1968 most residents of Duval County voted to approve consolidation between the county and the City of Jacksonville. Jacksonville Beach, together with Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and the Westside community of Baldwin voted to retain their own municipal governments. As such they are not part of the City of Jacksonville, but receive county-level services from Jacksonville, and vote for Jacksonville's mayor and City Council. Judy Van Zant, widow of lead singer of Lynyrd Skynyrd Ronnie Van Zant, and her daughter Melody opened the Freebird Cafe in 1999. Freebird Live, as it later became, was a popular music venue that became a staple for Jacksonville Beach for 16 years until its closure in 2016.[16] In September 1999 Hurricane Floyd destroyed the Jacksonville Beach Pier. Five years later the pier was rebuilt.[17] In October 2016 Hurricane Matthew forced a mandatory evacuation for Jacksonville Beach.[18] Hurricane Matthew came 40 miles off the coast of Jacksonville Beach causing major flooding. The Jacksonville Beach Pier was partially destroyed by Hurricane Matthew.[19]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 22.0 square miles (56.9 km2). 7.3 square miles (19.0 km2) of it is land and 14.6 square miles (37.9 km2) of it (66.61%) is water.[6] Jacksonville Beach is the largest town in the Jacksonville Beaches community. It is the eastern terminus of U.S. Route 90, which ends at an intersection with State Road A1A three blocks from the Atlantic Ocean. The city is located at 30°17′3″N 81°23′46″W (30.284091, -81.396074).[20]

Cityscape

Architecture

In general, the architecture of Jacksonville varies in style and is not defined by any one characteristic, and Jacksonville Beach is no exception. Designed by Marsh and Saxelbye, and completed in 1925, Casa Marina Hotel is a Mission style hotel popular in the 1920s when Jacksonville's beaches were being developed. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 2, 1993.[21] Constructed in 1947, the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps Station is an Art Moderne style lifeguard station designed by local architect Jefferson Davis Powell. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 5, 2014.[22] Jacksonville Beach is also home to a notable collection of Mid-Century modern architecture. Perhaps the most notable of these works are those designed by architect William Morgan.[23]

Casa Marina Hotel (1925)

Casa Marina Hotel (1925)

City Hall

City Hall Seawalk Pavilion

Seawalk Pavilion

Climate

Jacksonville Beach has a humid subtropical climate.

| Climate data for Jacksonville Beach | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

97 (36) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

89 (32) |

85 (29) |

103 (39) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.5 (17.5) |

64.7 (18.2) |

70.0 (21.1) |

75.8 (24.3) |

81.8 (27.7) |

86.7 (30.4) |

89.3 (31.8) |

88.0 (31.1) |

85.2 (29.6) |

79.0 (26.1) |

71.9 (22.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

76.8 (24.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 45.6 (7.6) |

47.5 (8.6) |

52.9 (11.6) |

58.7 (14.8) |

65.8 (18.8) |

71.6 (22.0) |

73.5 (23.1) |

73.8 (23.2) |

72.5 (22.5) |

64.9 (18.3) |

56.3 (13.5) |

48.6 (9.2) |

61.0 (16.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 14 (−10) |

21 (−6) |

24 (−4) |

37 (3) |

47 (8) |

55 (13) |

57 (14) |

63 (17) |

53 (12) |

38 (3) |

25 (−4) |

15 (−9) |

14 (−10) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.56 (90) |

2.84 (72) |

3.92 (100) |

2.87 (73) |

3.03 (77) |

5.70 (145) |

5.21 (132) |

6.11 (155) |

7.53 (191) |

5.04 (128) |

2.36 (60) |

2.75 (70) |

50.92 (1,293) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.7 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 108.4 |

| Source: NOAA (normals, 1971–2000)[24] | |||||||||||||

Parks and recreation

Hanna Park is a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) public beach and city park located near Mayport in the Jacksonville Beaches area. It consists of 447 acres (1.81 km2) of mature coastal hammock, and was formerly known as Manhattan Beach, Florida's first beach community for African Americans during the period of segregation in the United States.[25]

Beach access point

Beach access point Jacksonville Beach Pier

Jacksonville Beach Pier- Sea Walk Pavilion

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 249 | — | |

| 1920 | 357 | 43.4% | |

| 1930 | 409 | 14.6% | |

| 1940 | 3,566 | 771.9% | |

| 1950 | 6,430 | 80.3% | |

| 1960 | 12,049 | 87.4% | |

| 1970 | 12,779 | 6.1% | |

| 1980 | 15,462 | 21.0% | |

| 1990 | 17,839 | 15.4% | |

| 2000 | 20,990 | 17.7% | |

| 2010 | 21,362 | 1.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 23,628 | [4] | 10.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] 2018 Estimate[27] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 20,990 people, 9,715 households, and 5,207 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,732.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,055.2/km2). There were 10,775 housing units at an average density of 1,402.6 per square mile (541.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.94% White, 4.82% African American, 0.27% Native American, 1.63% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.79% from other races, and 1.51% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.99% of the population.

There were 9,715 households, out of which 21.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.5% were married couples living together, 9.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.4% were non-families. 34.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.78.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 18.0% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 35.6% from 25 to 44, 24.7% from 45 to 64, and 13.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 99.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $46,922, and the median income for a family was $58,388 (these figures had risen to $62,897 and $80,054 respectively as of a 2007 estimate). Males had a median income of $36,385 versus $30,055 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,467. About 4.2% of families and 7.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.2% of those under age 18 and 7.0% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Since the 1968 consolidation between Duval County and the City of Jacksonville, Jacksonville Beach has been a separate municipality within the consolidated city of Jacksonville. As such, it has its own city manager, city council, and mayor, but it is subject to county-level governance by Jacksonville. The current mayor is Charlie Latham[28] who was re-elected to a second four-year term in November 2016.

Transportation

Beach Boulevard (US 90) connects Jacksonville Beach to the Southside neighborhood of Jacksonville. It continues westward to downtown Jacksonville, via the Commodore Point Expressway and Hart Bridge. Butler Bouleveard (SR 202) begins in southeast Jacksonville at Philips Highway (US 1) and ends in southern Jacksonville Beach at 3rd Street South (SR A1A). SR A1A is a popular seaside scenic route extending from Fernandina Beach to Key West. In Jacksonville Beach it serves as the main commercial corridor, extending the length of the beachside community.

Education

The Duval County Public Schools district operates public schools, including San Pablo Elementary School in Jacksonville Beach.

Notable people

- Billy Horschel (born 1986), professional golfer.

- Jonas Blixt (born 1984), professional golfer.

- David Lingmerth (born 1987), professional golfer.

- Matt Every (born 1983), professional golfer.

- Donna Orender (born 1957), sports executive, former college and professional basketball player.

- Francis E. Spinner (1802-1890), Treasurer of the United States during the Civil War.[29]

- Ben Cooper (born 1982), musician

- Bobby BK Kennedy, professional skateboarder [Pepsi-Cola].

- Jimmy Plumer, professional skateboarder [z-flex].

- Benjaman Kyle*

- Tim Tebow (born 1987), professional baseball player, former professional football player.

See also

References

- "History: Jacksonville Beach". City of Jacksonville Beach. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Jacksonville Beach city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- "History of the City of Jacksonville Beach". Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- " First Settlers at Ruby, Florida." Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources, 2011. Web. 28 Dec 2011. < "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) >

- Showing its Statistics, Resources, Lands, Products, Climate and Populations. The county Commissioners. 1885. Retrieved 2011-12-23 https://archive.org/stream/duvalcountyflori00duva#page/n5/mode/2up

- T. Frederick Davis, History of Jacksonville, Florida and vicinity, 1513 to 1924, Florida Historical Society, 1925.http://ufdc.ufl.edu/NF00000013/00001/Retrieved 2011-12-23

- "History". jacksonvillebeach.org. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Our History." Our History: Greater Metro North & North Shore History. North Shore Neighborhood Association. 1999. Web. 23 Dec. 2011. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-06-30. Retrieved 2011-12-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "When The Spanish–American War Came To Springfield". metrojacksonville.com. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "The Rise and Fall of Jacksonville Beach Amusement Parks". metrojacksonville.com. metrojacksonville.com. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Doolittle's 1922 Record Flight." Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources, 2011. Web. 28 Dec 2011. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) >

- Soergel, Matt (January 14, 2016). "Jacksonville Beach's iconic Freebird club closing after 16 years". The Florida-Times Union. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- "Comparing Hurricane Matthew to track of Hurricane Floyd in 1999". Action News Jax. October 4, 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "MANDATORY EVACUATION FOR JACKSONVILLE BEACH". Beaches Leader. October 6, 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Donovan, Brittney. "Jacksonville Beach Pier damaged by Hurricane Matthew". Action News Jax. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps Station Registration Form" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- "American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps Station Registration Form" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- "When Does Modern Architecture Become Historic?". Jacksonville Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- "Climatography of the United States No. 20 (1971–2000)" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- "Hanna Park". City of Jacksonville. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- "Mayor & City Council - City of Jacksonville Beach". www.jacksonvillebeach.org. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- T. Frederick Davis, History of Jacksonville, Florida and vicinity, 1513 to 1924, The Florida Historical Society, 1925. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/NF00000013/00001/ Retrieved 2011-12-23

External links

- Official website