Indooroopilly, Queensland

Indooroopilly /ˌɪndrəˈpɪli/ is a western suburb in the City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.[3] In the 2016 census, Indooroopilly had a population of 12,242 people.[1]

| Indooroopilly Brisbane, Queensland | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Indooroopilly | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 27.5038°S 152.98°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 12,242 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,774/km2 (4,600/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 4068 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 6.9 km2 (2.7 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 7.8 km (5 mi) from Brisbane GPO | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Brisbane (Walter Taylor Ward)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Ryan | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Geography

Indooroopilly is bounded to the south and south-east by the Brisbane River. Indooroopilly is connected to Chelmer on the southern bank of the river by four bridges, consisting (from east to west) of a pedestrian/cycling bridge (Jack Pesch Bridge), two rail bridges (Albert Bridge and Indooroopilly Railway Bridge), and one road bridge (Walter Taylor Bridge).[4]

The suburb is designated as a regional activity centre.[5]

Indooroopilly boasts significant commercial, office and retail sectors and is home to Indooroopilly Shopping Centre, the largest shopping centre in Brisbane’s western suburbs. The suburb is popular with professionals and a large number of university students from the nearby University of Queensland campus in St Lucia. The housing stock consists of a mix of detached houses and medium density apartments. There has been a trend towards increasing small lot and townhouse development in the suburb in recent years. Nevertheless, many post-war homes and iconic Queenslanders have also been restored. Brisbane City Council regulations to preserve the 'pre-war' look of Brisbane discourage destruction of many of Brisbane's Queenslanders and buildings. It is one of the Brisbane City Council's proposed Major Centres.

History

The name Indooroopilly has been the subject of debate, but is most likely a corruption of either the local Aboriginal word nyindurupilli, meaning 'gully of the leeches' or yindurupilly meaning 'gully of running water'.[3][6][7][8][9]

The traditional owners of the Indooroopilly area are the Aboriginal Jagera and Turrbal groups. Both groups had related languages and are classified as belonging to the Yaggera language group.

The area was first settled by Europeans in the 1860s and agriculture and dairying were common in the early years.

The parish was named in the late 1850s, and the first house was built in 1861 by Mr H C Rawnsley.

Toowong Mixed State School opened in 1870. In 1879 it was renamed Indooroopilly State School. In 1888 it was renamed Indooroopilly Pocket State School. In 1905 it was renamed Ironside State School, which is now in the suburb of St Lucia (and is not the current Indooroopilly State School).[10]

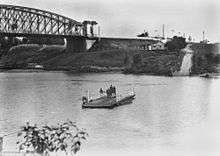

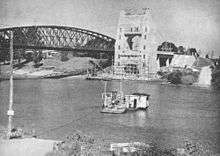

The arrival of rail in 1875 and completion of the Albert rail bridge across the Brisbane River to open the Ipswich rail line the following year spurred the development of Indooroopilly.

On 3 June 1878 auctioneer John Cameron offered 54 suburban allotments in the Henderson Estate which was bounded by Lambert Road to the north, Clarence Road to the west and the Brisbane River to the south. The lots were mostly 32 perches (810 m2) except for the riverside lots which were larger.[11][12] The sale was not completely successful as a further auction of the same estate was held on 6 December 1879 and again on 27 July 1880.[13][14]

Indooroopilly State School opened on 7 July 1889 (this is the school still in Indooroopilly today).[10]

The 1893 Brisbane flood destroyed the original Albert Bridge, and its replacement was opened in 1895.

On 7 August 1909 auctioneer G.H. Blocksidge offered 60 suburban allotments, all 16 perches (400 m2), in the Waverley Estate, which was bounded by Stanley Street to the west, Waverley Road to the north and Adelaide Street (now Woolley Street) and Nelson Street to the east.[15][16]

A lead-silver mine was established on an Indooroopilly property in 1919 and extraction continued until 1929 when the mine became unprofitable. Today the University of Queensland operates the site as an experimental mine and teaching facility for engineering students (the Julius Kruttschnitt Mineral Research Centre).

On Sunday 14 March 1926 Monsignor James Byrne laid the foundation stone of the Church of the Holy Family.[17] On Sunday 4 July 1926 Monsignor Byrne opened and dedicated the new building to be used as both a church and a school. The church of the Holy Family is a wooden structure of 60 by 25 feet (18.3 by 7.6 m) with two 10 feet (3.0 m) verandahs. The architects were Messrs Hall and Prentice, and the contractor Mr R Robinson. The cost of the building was £2500 and the land something exceeding £4000. Against this a donation of £1000 had been received while at the foundation stone ceremony £500 was received and the donations at the opening were £400.[18] However, it was not until late 1927 that five Brigidine Sisters relocated from Randwick in Sydney to Indooroopilly to occupy the house Warranoke (built in 1888-1889 for Gilson Foxton and designed by architects Oakden, Addison and Kemp).[19] The Sisters opened Holy Family Primary School in the church-school building on 19 February 1928.[10][20] The Sisters opened Brigidine College in Warranoke in 1929.[21]

The landmark Walter Taylor Bridge across the Brisbane River was completed in 1936.

In 1936 Roman Catholic Archbishop James Duhig granted 25 acres (10 ha) of river front land on the Chelmer Reach of the Brisbane River to the Christian Brothers to establish a junior preparatory school for St Joseph's College at Nudgee to relieve the pressure on the boarding school at Nudgee.[22] St Joseph's Nudgee Junior College opened and blessed by Duhig on 10 July 1938. The first principal was Brother J.M. Wynne. In the first year of operation there 46 boarders and 6 day pupils.[10][23]

Indooroopilly was the location for Australia's principal interrogation centre during World War II. The three interrogation cells at Witton Barracks are the only cells remaining in the country.[24]

St Peter's Lutheran College opened on 25 February 1945 in the 1897 villa Ross Roy. Its primary school St Peter's Lutheran Junior College opened on the same day but ceased to operate independently on 31 December 2001.[10]

Indooroopilly State High School opened on 2 February 1954.[10]

The first stage of Indooroopilly Shoppingtown opened in 1970.

The Indooroopilly Library opened in 1981 in Indooroopilly Shoppingtown and had a major refurbishment in 2011.[25]

In 1995 the boarding school at St Joseph's Nudgee Junior College was closed and the boarders transferred to the main school at Nudgee. The school had approximately 300 day students in that year.[23]

In the 2011 census, Indooroopilly had a population of 11,670 people.[26]

In 2014 St Joseph's Nudgee Junior College closed as the Queensland Government decision to move Year 7 from primary school to secondary school would have left the school struggling to survive with the smaller number of students, so the decision was taken to close the primary school feeding into the Nudgee secondary school and replace it with a new Catholic primary and secondary school. In 2015 a new Catholic school Ambrose Treacy College (named in honour of Ambrose Treacy) opened on the site, operating n the Edmund Rice tradition, with many students transferring from the old to the new school.[23][27]

In the 2016 census, Indooroopilly had a population of 12,242 people.[1]

Heritage listings

Indooroopilly has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- Brisbane River between Indooroopilly and Chelmer: Albert Bridge[28]

- 203 Clarence Road: Tighnabruaich[29]

- Coonan Street: Walter Taylor Bridge[30]

- 47 Dennis Street: Greylands[31]

- Harts Road: Thomas Park Bougainvillea Gardens[32]

- 60 Harts Road: Ross Roy[33]

- 66 Harts Road: Chapel of St Peter's Lutheran College[34]

- 9 Lambert Road: Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre[35]

- 72 Lambert Road: St Andrews Church Hall[36]

- Ward Street: Indooroopilly State High School Buildings[37]

- 53 Ward Street: former Warranoke (now part of Brigidine College)[38]

- 10-12 Westminster Road: Keating residence[39]

Demographics

In the 2011 census, Indooroopilly had a population of 11,670 people; 50.9% female and 49.1% male.[26] The median age of the Indooroopilly population was 29 years of age, 8 years below the Australian median. The most notable difference is the group in their twenties; in Indooroopilly this group makes up 28.5% of the population, compared to 13.8% nationally. Children aged under 15 years made up 13.9% of the population and people aged 65 years and over made up 10.2% of the population. 60% of people living in Indooroopilly were born in Australia, compared to the national average of 69.8%. The other top responses for country of birth were China 3.7%, England 3.2%, New Zealand 2.5%, India 2.1%, Malaysia 1.8%. 70.4% of people spoke only English at home; the next most popular languages were 6.3% Mandarin, 2.2% Cantonese, 1.7% Arabic, 1.2% Korean, 0.9% Spanish. The most common responses for religion in Indooroopilly were No Religion 29.7%, Catholic 20.6%, Anglican 13.1%, Uniting Church 5.1% and Buddhism 3.1%.[26]

Transport

Moggill Road is the main thoroughfare, connecting Indooroopilly to Toowong and the city via Coronation Drive (inbound), and Chapel Hill and Kenmore (outbound). The Western Freeway also serves the suburb. Indooroopilly is well connected by public transport. There is a bus interchange adjoining the Indooroopilly Shopping Centre, where Brisbane Transport operates services to the CBD, university and other western suburbs. Indooroopilly railway station provides frequent services to the Brisbane CBD, Ipswich, Richlands and Caboolture.

Amenities

There is a café and restaurant precinct along Station Road between the shopping centre and railway station as well as to the east of the railway station. There are two cinema complexes in Indooroopilly, the Eldorado cinemas on Coonan Street and Event Cinema Megaplex inside Indooroopilly Shopping Centre. This cinema complex once had 8 cinemas, now it boasts 16. It is the major cinema complex in the Western Suburbs. Indooroopilly youth organisations include the Indooroopilly Scout Group including Rovers[40] and Indooroopilly Girl Guide District[41] Indooroopilly is also home to one of Brisbane's oldest Soccer Football Clubs, Taringa Rovers. The Indooroopilly Golf Club[42] is a 36-hole championship course offering members and guests a variety of competition and social golf.

The Brisbane City Council operate a public library in the Indooroopilly Shopping Centre (Station Road end).[43]

Education

Indooroopilly State School is a government primary (Prep-6) school for boys and girls at the corner Moggill Road and Russell Terrace (27.5003°S 152.9654°E).[44][45] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 989 students with 66 teachers (60 full-time equivalent) and 34 non-teaching staff (20 full-time equivalent).[46] It includes a special education program.[44]

Indooroopilly State High School is a government secondary (7-12) school for boys and girls at Ward Street (27.5005°S 152.9840°E).[44][47] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 1,834 students with 153 teachers (141 full-time equivalent) and 65 non-teaching staff (44 full-time equivalent).[46] It include a special education unit.[44]

Holy Family Primary School is a Catholic primary (Prep-6) school for boys and girls at Ward Street (27.4999°S 152.9800°E).[44][48] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 250 students with 23 teachers (15 full-time equivalent) and 16 non-teaching staff (10 full-time equivalent).[46]

Ambrose Treacy College is a Catholic primary and secondary (4-10) school for boys at Twigg Street (27.5075°S 152.9669°E).[44][49] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 851 students with 66 teachers (60 full-time equivalent) and 82 non-teaching staff (57 full-time equivalent).[46]

Brigidine College is a Catholic secondary (7-12) school for girls at 53 Ward Street (27.5005°S 152.9804°E).[44][50] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 807 students with 66 teachers (64 full-time equivalent) and 47 non-teaching staff (33 full-time equivalent).[46]

St Peters Lutheran College is a private primary and secondary (Prep-12) school for boys and girls at 66 Harts Road (27.5059°S 152.9828°E).[44][51] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 1,992 students with 188 teachers (175 full-time equivalent) and 144 non-teaching staff (118 full-time equivalent).[46]

The Japanese Language Supplementary School of Queensland Japanese School of Brisbane (ブリスベン校 Burisuben Kō), a weekend Japanese school, holds its classes at Indooroopilly State High School. The school offices are in Taringa.[52]

See also

- List of Brisbane suburbs

- Bridges over the Brisbane River

- Taringa Rovers Soccer Football Club

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Indooroopilly (SSC)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Walter Taylor Ward". Brisbane City Council. Brisbane City Council. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- "Indooroopilly - suburb in City of Brisbane (entry 47381)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- "Queensland Globe". State of Queensland. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Tony Moore (9 December 2011). "Indooroopilly's future: Tall buildings, outdoor dining and possibly a new bridge". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Petrie, Constance Campbell; Petrie, Tom, 1831-1910 (1980). Tom Petrie's reminiscences of early Queensland (PDF). Currey O'Neil. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-85550-278-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "MEANING OF INDOOROOPILLY". The Courier-mail. Queensland, Australia. 28 August 1933. p. 25. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ""MEANING OF INDOOROOPILLY". The Courier-mail. Queensland, Australia. 9 November 1935. p. 12. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- "Indooroopilly and Yeerongpilly". The Courier-mail. Queensland, Australia. 14 November 1935. p. 23. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- Queensland Family History Society (2010), Queensland schools past and present (Version 1.01 ed.), Queensland Family History Society, ISBN 978-1-921171-26-0

- "Plan of the Henderson Estate". 1878. hdl:10462/deriv/280201. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Advertising". The Telegraph (1, 753). Queensland, Australia. 1 June 1878. p. 4. Retrieved 29 October 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Classified Advertising". The Brisbane Courier. XXXIV (3, 917). Queensland, Australia. 6 December 1879. p. 8. Retrieved 29 October 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Classified Advertising". The Brisbane Courier. XXXV (4, 113). Queensland, Australia. 27 July 1880. p. 4. Retrieved 29 October 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "The Waverley Estate". 1909. hdl:10462/deriv/280881. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Advertising". The Brisbane Courier. LXVI (16, 088). Queensland, Australia. 4 August 1909. p. 8. Retrieved 29 October 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "No title". The Brisbane Courier. Queensland, Australia. 17 March 1926. p. 10. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- "HOLY FAMILY CHURCH". The Brisbane Courier. Queensland, Australia. 5 July 1926. p. 8. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- "CATHOLIC PROGRESS". The Brisbane Courier. Queensland, Australia. 2 January 1928. p. 12. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- "Our History". Holy Family Primary School. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "College History". Brigidine College. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "BOARDING SCHOOL AT INDOOROOPILLY". The Courier-mail. Queensland, Australia. 28 August 1936. p. 15. Retrieved 29 March 2020 – via Trove.

- "History". Ambrose Treacy College. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Tony Moore (24 July 2015). "Brisbane's top secret prison cells to be protected in bridge plan". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- "Public Libraries Statistical Bulletin 2016-17" (PDF). Public Libraries Connect. State Library of Queensland. November 2017. p. 11. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Indooroopilly (State Suburb)". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Ng, Emilie (6 February 2015). "Historic change in education". The Catholic Leader. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Albert Bridge (entry 600232)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Tighnabruaich (entry 600229)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Walter Taylor Bridge (entry 600181)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Greylands (entry 600230)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Thomas Park Bougainvillea Gardens (entry 602838)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "Ross Roy". Brisbane Heritage Register. Brisbane City Council. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- "Chapel of St Peter's Lutheran College, Indooroopilly (entry 602816)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre (former) (entry 650030)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- "St Andrews Church Hall (entry 600231)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Indooroopilly State High School (entry 650035)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Warranoke (former)". Brisbane Heritage Register. Brisbane City Council. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Keating Residence, Indooroopilly (entry 602057)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- Indooroopilly Rovers (Scouts)

- Indooroopilly Girl Guides

- Indooroopilly Golf Club

- "Indooroopilly Library". Public Libraries Connect. State Library of Queensland. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "State and non-state school details". Queensland Government. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Indooroopilly State School". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "ACARA School Profile 2017". Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Indooroopilly State High School". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Holy Family Primary School". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Ambrose Treacy College". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Brigidine College". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "St Peters Lutheran College". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "平成 26(2014)年度" (Archive). The Japanese Language Supplementary School of Queensland. Retrieved on 1 April 2015. p. 4. "借用校舎:インドロピリー州立高校(Indooroopilly State High School) Ward Street, Indooroopilly, QLD4068, AUSTRALIA 事務所:The Japanese Club of Brisbane/The Japanese School of Brisbane Suite 17, Taringa Professional Centre, 180 Moggill Road, Taringa, QLD4068"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indooroopilly, Queensland. |

- "Indooroopilly". Queensland Places. Centre for the Government of Queensland, University of Queensland.

- "Indooroopilly". BRISbites. Brisbane City Council. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008.

- "Indooroopilly". Our Brisbane. Brisbane City Council. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008.

- Local History - Indooroopilly

- Indooroopilly: the tongue twisting waltz song hit - virtual book. Digitised and held by State Library of Queensland.