Incisitermes minor

Incisitermes minor is a species of termite in the family Kalotermitidae known commonly as the western drywood termite. It is native to western North America, including the western United States and northern Mexico. It has been found in many other parts of the United States, all the way to the East Coast. It has been reported from Toronto.[1] It has been introduced to Hawaii.[2] It has been noted in China and it is not uncommon in Japan.[1] This is an economically important pest of wooden structures, including houses. In California and Arizona alone its economic impact is estimated to be about $250 million per year.[1]

| Incisitermes minor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | I. minor |

| Binomial name | |

| Incisitermes minor Hagen, 1858 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Kalotermes minor | |

Within a single colony there are three types of termites, the alates, soldier, and worker. This eusocial species is a dark brown color and has an orange head.[1] The colonies are most active during the spring and summer, preferring to be active in higher temperatures.[3]

Morphology

There are three types of termites within the colony: the alate (swarmer), the soldier and the worker. Alates have an orange-brown head and pronotum, an 11-12.5 mm long, dark brown abdomen. This is the only caste that leaves the colony, which happens when they seek a mate. If they are successful, they will form the new kings and queens.[1][4] There are also soldiers, which are large, reddish-brown, and have two teeth visible on the left mandible. They are noted for having a larger third antennal segment. They are 8–12 mm long, and can weigh from 20–25 mg.[1] This eusocial species does not have a normal worker caste. There are “pseudergates” which are false workers characterized by their lack of wing pads, as well as "nymphs" which do possess wing pads. These wing pads allow the nymphs to molt into a soldier or an alate, because they are not sterile. These workers are not the bottom class, meaning they are capable of becoming soldiers and alates.[1] The pseudergates group is also able to change into male or female alates just by molting, which is very different from other insect species.[5]

They are dark brown and have an orange head. The soldiers are larger than the alates, and they reach an average length of 0.4 inches, and have a broad red head with black mandibles. They have a larger third segment as well.

Distribution

In the United States the termite is found in northern California, Oregon, and Washington. In California it is found mainly in the central valley. It is also found in central Arizona and into Baja California and Sonora.[1] Due to travel there has also been isolated groups of this termite found in other states, particularly Florida. Infestations have been found in Arkansas, Iowa, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Ohio, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana. There have also infestations in China and Japan.[1]

Habitat

This termite is adapted to the Mediterranean climate of its native range in California and the surrounding regions. It is a relatively dry climate with hot summers and little rainfall in many areas. It lives in California oak woodland and other local ecosystems, where it inhabits trees. It builds its nests in dead parts of California bay laurel, willows, cottonwoods, oaks, and sycamores, and in stumps, fallen branches, and logs. Nearer to human-inhabited areas it lives in many types of native, introduced, and cultivated plants, such as roses, pyracantha, oleander, alder, ash, avocado, carob, citrus, elderberry, mulberry, walnut, and many kinds of Prunus.[1]

It is able to persist in other climate types, as evidenced by its isolated occurrences across North America, including many in Florida, and its establishment in Japan.[1]

It also does not require plants. It just as easily builds its colonies in wooden structures. It is a household pest. It has been introduced to new areas in shipments of wooden furniture and lumber. It has been observed colonizing a wooden bench.[1] In structures it infests wood flooring, window frames, door frames, fascia boards, and soffits. It occupies utility poles.[6] In Japan it infests tatami.[7]

Life cycle and reproduction

Termites swarm in order to reproduce. This is when large groups of the termite gather in a specific location to mate, before going separate ways to establish colonies. The alate group engages in the swarming behavior. The alate group swarms in late September through November in Southern California. On warmer days, the termites will swarm earlier in the day.[1] Swarming occurs on days with temperatures between 26.7–37.8 °C (80 to 100 °F). The alates emerge from inside the wood nest, and as they reach the outside they will take off. The alates are not able to fly well, and therefore do not move far from their emergence point. When they land, they remove their wings and crawl around (wingless) to find a mate. Once a mate is found they engage in courtship activity.[1] In finding a mate, the females crawl with the male behind. Once the female accepts the male they are now mated for life, and are now the king and the queen. In order to begin a colony, the male and female have to find a piece of wood with a hole in it, which they will enter and create a royal cell.[1] This whole process can take three to four days. When they are done excavating they have to plug the hole with gut contents.[1]

Afterwards they enter a long period of inactivity, for approximately nine months; during this period the queen will begin to lay eggs. After nine months the eggs are hatched and the queen and king feed them until they can begin to excavate the wood.[1] Eventually the new termites will be able to consume wood on their own. At this point they will be a wingless worker caste that will forage and begin to feed the next generation of new termites. They are the ones that damage the wood as they eat and digest it to feed and take care of the nest.[8] In the next two years as more eggs hatch, the king and queen have a small colony, including a soldier and probably a dozen or so nymphs. Each termite has seven instars, which are different developmental stages after which they shed their skin and assumed different body forms. It can take about a year for the termite to go from egg to maturity.[1] With time the females undergo physogastry – where the ovaries enlarge and the abdomen swells. The kings look the same as when he dropped his wings.[1] As the colony matures and workers mature, they will become either soldiers or reproductives. The reproductives will be the new swarmers will exit the wood to form new colonies. Those alates will then go on to mate and form their own nests.[8]

The colonies are slow growing. It can take five to seven years before there is visible damage in the wood from feeding. There are also secondary reproductive pairs that can appear, but it is very rare. There are only multiple pairs if it is a mixture of two different colonies.[1]

Behavior

Like other termites, this species is eusocial, living in a colony with a caste system. There are different types of adult insect: the alate, or swarmer, the soldier, and the pseudergate. The alates are the swarmers, and they can be male or female.[1] The eusocial groups are important because it allows them to have multiple generations that can take care of the young. It also allows for specialization, so that there is a specific class that can be best suited to defending the nest and other which are better at foraging.[9]

Food gathering

The termites feed on wood and excavate very similarly to other termites. Their feeding behavior results in larger, more cavernous, irregular evacuations. I. minor also excavates toward the outer edge of the food, but it does not break the wood. They accomplish this by leaving a thin, outer layer, which is protective. This often gives the wood the appearance of being strong, but it is still weakened from the eating on the inside.[1] The termites are also known to feed on dead tree branches, and not just feeding on live trees.[10] There is also a feeding hierarchy within the colony. In an experiment, filter paper was marked with Rb (Rubidium) to show that not all the termites in the colonies feed. The analysis of the Rb levels indicated that in the hierarchy the nymphs are the primary donors, the primary eaters, and the larvae are the primary recipients. This experiment is able to show this because those that directly eat the Rb labeled filter paper have a higher concentration of Rb in their body than those termite that are eating the food second hand after being fed. The alates might also require more care before swarming.[11]

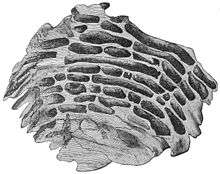

As the termites eat, they leave very little signs that they are present in the wood. However, they do have a small hole on the surface of the wood through which they eject their fecal pellets. The fecal pellets are hard, and evenly shaped, and found in conical piles or scattered on horizontal surfaces. The fecal pellets have the same hydrocarbons as the species of termite, and each termite has unique cuticular hydrocarbons.[12] Many other species of termites have bacterial and fungal loads that exist with the colonies, but I. minor prefer drier forms of wood have very small bacterial and fungal microbial loads.[13]

The termites do have a preference to the type of wood that they like to consume. The termites are most likely to eat wood that is not tainted with repellent chemicals in the wood. The termites are also more likely to consume wood from which the colony has developed. The Douglas fir is the most popular wood that the termites like to consume. Termites that were exposed to extracts of least-preferred wood have a slight increase in mortality, indicating that the type of wood is important for survival.[14] The strain of wood that was least preferred was a strain of commercial timber called Karamatsu wood. This strain experienced the lowest loss in mass and is therefore considered the most resistant.[15]

Activity levels

The termite's activity is associated with the temperature. Termite activity is highest during the spring and summer. However, an increase in temperature, even in the winter months, can cause an increase in activity. Activity is also lowest during the morning, peaking in the later afternoon. There is a very strong correlation between the temperature and the activity of the termites. As there is an increase in temperature there is an increase in activity.[3] As the termites are more activity, they have an increase in the release of CO2.[16]

Impacts

This species is probably the most destructive of the dryland termite species in the western United States,[6] while rhinotermitidae subterranean termite damage is more costly.[12] The western subterranean termite (Reticulitermes hesperus) is considered to be the worst termite pest in California, with I. minor in second place.[17]

In Southern California, it is estimated that this species represents about half of all reports of wood-destroying organisms, and much more closer to the coastline. Urban sprawl will likely increase populations.[1]

It will also probably continue to spread to new areas. It was discovered in the historic New Orleans building Perseverance Hall in 1999, where it was probably introduced in furniture shipped from the west.[10] One common vector of introduction is the boat, such as the yachts and other craft that launch from Southern California. The termite was noted in Australia after having been inadvertently delivered by boat.[18]

Management

As a pest of human habitation, this termite has been the target of many pest control methods.

In severe infestations a structure may be tented and fumigated with sulfuryl fluoride. This generally kills all the termites in the structure. Less extreme spot treatments can be made by drilling into the gallery and injecting pesticide,[1] such as pyrethroids or imidacloprid.[17] A gel bait containing hydramethylnon has been effective in experiments.[19]

In the movement away from pesticides other treatments have been developed, such as the blasting of hot air into the colonies, or the application of liquid nitrogen. A microwave-emitting device can be used to "cook" the colony, or a low-current, high-voltage "gun" device can deliver an electric shock.[1]

If possible, infested wood can simply be removed from the structure and replaced, and infested trees or dead wood piles can be removed.[1]

References

- Cabrera, B. J. and R.H. Scheffrahn. Western drywood termite (Incisitermes minor). Publication Number EENY-248. University of Florida IFAS Extension and Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. 2001. Revised 2005.

- Haverty, M. I.; et al. (2000). "Cuticular hydrocarbons of termites of the Hawaiian Islands" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Ecology. 26 (5): 1167–91. doi:10.1023/A:1005479826651.

- Lewis, Vernard; et al. (12 December 2011). "Seasonal and Daily Patterns in Activity of the Western Drywood Termite, Incisitermes minor (Hagen)". Insects. 2 (4): 555–563. doi:10.3390/insects2040555. PMC 4553448.

- Walker, K. "Western Drywood Termite". PaDIL.

- "Western Drywood Termite, Incisitermes minor". redOrbit. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- Baker, P. B. and R. J. Marchosky. Arizona Termites of Economic Importance. AZ1369. Cooperative Extension, University of Arizona. Tucson. 2005.

- Indrayani, Y. and T. Yoshimura. (2006). Feeding ecology of the invasive dry-wood termite Incisitermes minor (Hagen) in Japan. Sustainable Humanosphere: The Bulletin of the Research Institute for Sustainable Humanosphere. Kyoto University. 2 11.

- Gold, Roger E.; Glenn, Grady J.; Howell, Harry N., Jr.; Brown, Wizzie. "Drywood Termites". AgriLife Communications and Marketing, Texas A&M University System. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- Davies, Nicholas B., John R. Krebs, Stuart A. West (2012). An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology. Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing.

- Messenger, M. T.; et al. (2000). "First report of Incisitermes minor (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae) in Louisiana" (PDF). The Florida Entomologist. 83 (1): 92–3. doi:10.2307/3496233. JSTOR 3496233.

- Cabrera, B.J.; M. K. Rust (July 1999). "Caste differences in feeding and trophallaxis in the western drywood termite, Incisitermes minor (Hagen) (Isoptera, Kalotermitidae)". Insectes Sociaux. 46 (3): 244–249. doi:10.1007/s000400050141.

- Lewis, V. R.; et al. (2010). "Quantitative changes in hydrocarbons over time in fecal pellets of Incisitermes minor may predict whether colonies are alive or dead". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 36 (11): 1199–1206. doi:10.1007/s10886-010-9864-5. PMC 2980652. PMID 20882326.

- Rosengaus, Rebeca B.; et al. (2003). "Nesting ecology and cuticular microbial loads in dampwood (Zootermopsis angusticollis) and drywood termites (Incisitermes minor, I. schwarzi, Cryptotermes cavifrons)". Journal of Insect Science. 31. 2 (31): 1–6. doi:10.1673/031.003.3101. PMC 524670.

- Rust, Michael K.; Donald A. Reierson (July 1977). "Using wood extracts to determine the feeding preferences of the western drywood termite, Incisitermes minor (Hagen)". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 3 (4): 391–399. doi:10.1007/bf00988182.

- Indrayani, Yuliati; et al. (June 2007). "Feeding responses of the western dry-wood termite Incisitermes minor (Hagen) (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae) against ten commercial timbers". Journal of Wood Science. 53 (3): 239–248. doi:10.1007/s10086-006-0840-1.

- Shelton, Thomas G; El al (June 2001). "Cyclic CO2 release in Cryptotermes cavifrons Banks, Incisitermes tabogae (Snyder) and I. minor (Hagen) (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 129 (2–3): 681–693. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00332-4.

- Lewis, V. R. Pest Notes: Drywood Termites. Publication 7440. Statewide IPM Program, Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California. 2002.

- Austin, J. W.; et al. (2012). "Mitochondrial DNA genetic diversity of the drywood termites Incisitermes minor and I. snyderi (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae)". The Florida Entomologist. 95 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1653/024.095.0112.

- Indrayani, Y.; et al. (2008). "A novel control strategy for dry-wood termite Incisitermes minor infestation using a bait system". J Wood Sci. 54 (3): 220–24. doi:10.1007/s10086-007-0934-4.