Prader–Willi syndrome

Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) is a genetic disorder caused by a loss of function of specific genes on chromosome 15.[3] In newborns, symptoms include weak muscles, poor feeding, and slow development.[3] Beginning in childhood, those affected become constantly hungry, which often leads to obesity and type 2 diabetes.[3] Mild to moderate intellectual impairment and behavioral problems are also typical of the disorder.[3] Often, affected individuals have a narrow forehead, small hands and feet, short height, light skin and hair, and are unable to have children.[3]

| Prader–Willi syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Labhart–Willi syndrome, Prader's syndrome, Prader–Labhart–Willi-Fanconi syndrome[1] |

| |

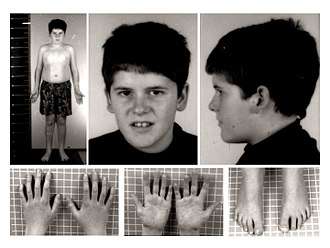

| Eight-year-old with Prader–Willi syndrome, exhibiting characteristic obesity[2] | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Medical genetics, psychiatry, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Babies: weak muscles, poor feeding, slow development[3] Children: constantly hungry, intellectual impairment, behavioural problems[3] |

| Complications | Obesity, type 2 diabetes[3] |

| Duration | Lifelong[4] |

| Causes | Genetic disorder (typically new mutation)[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Spinal muscular atrophy, congenital myotonic dystrophy, familial obesity[5] |

| Treatment | Feeding tubes, strict food supervision, exercise program, counseling[6] |

| Medication | Growth hormone therapy[6] |

| Frequency | 1 in 10,000–30,000 people[3] |

About 74% of cases occur when part of the father's chromosome 15 is deleted.[3] In another 25% of cases, the affected person has two copies of the maternal chromosome 15 from the mother and lacks the paternal copy.[3] As parts of the chromosome from the mother are turned off through imprinting, they end up with no working copies of certain genes.[3] PWS is not generally inherited, but rather the genetic changes happen during the formation of the egg, sperm, or in early development.[3] No risk factors are known for the disorder.[7] Those who have one child with PWS have less than a 1% chance of the next child being affected.[7] A similar mechanism occurs in Angelman syndrome, except the defective chromosome 15 is from the mother, or two copies are from the father.[8][9]

Prader–Willi syndrome has no cure.[4] Treatment may improve outcomes, especially if carried out early.[4] In newborns, feeding difficulties may be supported with feeding tubes.[6] Strict food supervision is typically required, starting around the age of three, in combination with an exercise program.[6] Growth hormone therapy also improves outcomes.[6] Counseling and medications may help with some behavioral problems.[6] Group homes are often necessary in adulthood.[6]

PWS affects between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 30,000 people.[3] The condition is named after Swiss physicians Andrea Prader and Heinrich Willi who, together with Alexis Labhart, described it in detail in 1956.[1] An earlier description was made in 1887 by British physician John Langdon Down.[10][11]

Signs and symptoms

PWS has many signs and symptoms. The symptoms can range from poor muscle tone during infancy to behavioral problems in early childhood. Some symptoms that are usually found in infants, besides poor muscle tone, are a lack of eye coordination, some are born with almond-shaped eyes, and due to poor muscle tone, some may not have a strong sucking reflex. Their cries are weak, and they have difficulty waking up. Another sign of this condition is a thin upper lip.[12]

More aspects seen in a clinical overview include hypotonia and abnormal neurologic function, hypogonadism, developmental and cognitive delays, hyperphagia and obesity, short stature, and behavioral and psychiatric disturbances.[13]

Holm et al. (1993) describe the following features and signs as indicators of PWS, although not all will be present.

Uterus and birth

- Reduced fetal movement

- Frequent abnormal fetal position

- Occasional polyhydramnios (excessive amniotic fluid)

- Often breech or caesarean births

- Lethargy

- Hypotonia

- Feeding difficulties (due to poor muscle tone affecting sucking reflex)

- Difficulties establishing respiration

- Hypogonadism

Childhood

- Delayed milestones/intellectual delay

- Excessive sleeping

- Strabismus (crossed eyes)

- Scoliosis (often not detected at birth)

- Cryptorchidism

- Speech delay

- Poor physical coordination

- Hyperphagia (overeating) begins between the ages of 2 and 8, and continues on throughout adulthood.

- Excessive weight gain

- Sleep disorders

- Delayed puberty

- Short stature

- Obesity

- Extreme flexibility

Adulthood

- Infertility (males and females)

- Hypogonadism

- Sparse pubic hair

- Obesity

- Hypotonia (low muscle tone)

- Learning disabilities/borderline intellectual functioning (but some cases of average intelligence)

- Prone to diabetes mellitus

- Extreme flexibility

Physical appearance

- Prominent nasal bridge

- Small hands and feet with tapering of fingers

- Soft skin, which is easily bruised

- Excess fat, especially in the central portion of the body

- High, narrow forehead

- Thin upper lip

- Downturned mouth

- Almond-shaped eyes

- Light skin and hair relative to other family members

- Lack of complete sexual development

- Frequent skin picking

- Stretch marks

- Delayed motor development

Neurocognitive

Individuals with PWS are at risk of learning and attention difficulties. Curfs and Fryns (1992) conducted research into the varying degrees of learning disability found in PWS.[14] Their results, using a measure of IQ, were as follows:

- 5%: IQ above 85 (high to low average intelligence)

- 27%: IQ 70–85 (borderline intellectual functioning)

- 39%: IQ 50–70 (mild intellectual disability)

- 27%: IQ 35–50 (moderate intellectual disability)

- 1%: IQ 20–35 (severe intellectual disability)

- <1%: IQ <20 (profound intellectual disability)

Cassidy found that 40% of individuals with PWS have borderline/low average intelligence,[15] a figure higher than the 32% found in Curfs and Fryns' study.[14] However, both studies suggest that most individuals (50–65%) fall within the mild/borderline/low average intelligence range.

Children with PWS show an unusual cognitive profile. They are often strong in visual organization and perception, including reading and vocabulary, but their spoken language (sometimes affected by hypernasality) is generally poorer than their comprehension. A marked skill in completing jigsaw puzzles has been noted,[16][17] but this may be an effect of increased practice.[18]

Auditory information processing and sequential processing are relatively poor, as are arithmetic and writing skills, visual and auditory short-term memory, and auditory attention span. These sometimes improve with age, but deficits in these areas remain throughout adulthood.[16]

PWS may be associated with psychosis.[19]

Behavioral

PWS is frequently associated with a constant insatiable appetite, which persists no matter how much the patient eats, often resulting in morbid obesity. Caregivers need to strictly limit the patients' access to food, usually by installing locks on refrigerators and on all closets and cabinets where food is stored.[20] It is the most common genetic cause of morbid obesity in children.[21] Currently, no consensus exists as to the cause for this symptom, although genetic abnormalities in chromosome 15 disrupt the normal functioning of the hypothalamus.[15] Given that the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus regulates many basic processes, including appetite, a link may well exist. In the hypothalamus of people with PWS, nerve cells that produce oxytocin, a hormone thought to contribute to satiety, have been found to be abnormal.

People with PWS have high ghrelin levels, which are thought to directly contribute to the increased appetite, hyperphagia, and obesity seen in this syndrome.[22] Cassidy states the need for a clear delineation of behavioral expectations, the reinforcement of behavioural limits, and the establishment of regular routines.

The main mental health difficulties experienced by people with PWS include compulsive behaviour (usually manifested in skin picking) and anxiety.[16][23] Psychiatric symptoms, for example, hallucinations, paranoia and depression, have been described in some cases[16] and affect about 5–10% of young adults.[15] Patients are also often extremely stubborn and prone to anger.[20] Psychiatric and behavioural problems are the most common cause of hospitalization.[24]

Typically, 70–90% of affected individuals develop behavioral patterns in early childhood.[13] Aspects of these patterns can include stubbornness, temper tantrums, controlling and manipulative behavior, difficulty with change in routine, and compulsive-like behaviors.[13]

Endocrine

Several aspects of PWS support the concept of a growth hormone deficiency. Specifically, individuals with PWS have short stature, are obese with abnormal body composition, have reduced fat-free mass, have reduced lean body mass and total energy expenditure, and have decreased bone density.

PWS is characterized by hypogonadism. This is manifested as undescended testes in males and benign premature adrenarche in females. Testes may descend with time or can be managed with surgery or testosterone replacement. Adrenarche may be treated with hormone replacement therapy.

Ophthalmologic

PWS is commonly associated with development of strabismus. In one study,[25] over 50% of patients had strabismus, mainly esotropia.

Genetics

PWS is caused by an epigenetic phenomenon known as imprinting, caused by the deletion of the paternal copies of the SNRPN and NDN necdin genes along with clusters of snoRNAs: SNORD64, SNORD107, SNORD108 and two copies of SNORD109, 29 copies of SNORD116 (HBII-85) and 48 copies of SNORD115 (HBII-52). These are on chromosome 15 located in the region 15q11-13.[26][27][28][29] This so-called PWS/AS region may be lost by one of several genetic mechanisms, which in the majority of instances occurs through chance mutation. Other, less common mechanisms include uniparental disomy, sporadic mutations, chromosome translocations, and gene deletions. Due to imprinting, the maternally inherited copies of these genes are virtually silent, and only the paternal copies of the genes are expressed.[30][31] PWS results from the loss of paternal copies of this region. Deletion of the same region on the maternal chromosome causes Angelman syndrome (AS). PWS and AS represent the first reported instances of imprinting disorders in humans.

The risk to the sibling of an affected child of having PWS depends upon the genetic mechanism which caused the disorder. The risk to siblings is <1% if the affected child has a gene deletion or uniparental disomy, up to 50% if the affected child has a mutation of the imprinting control region, and up to 25% if a parental chromosomal translocation is present. Prenatal testing is possible for any of the known genetic mechanisms.

A microdeletion in one family of the snoRNA HBII-52 has excluded it from playing a major role in the disease.[32]

Studies of human and mouse model systems have shown deletion of the 29 copies of the C/D box snoRNA SNORD116 (HBII-85) to be the primary cause of PWS.[33][34][35][36][37]

Diagnosis

It is traditionally characterized by hypotonia, short stature, hyperphagia, obesity, behavioral issues (specifically obsessive–compulsive disorder-like behaviors), small hands and feet, hypogonadism, and mild intellectual disability.[38] However, with early diagnosis and early treatment (such as with growth hormone therapy), the prognosis for persons with PWS is beginning to change. Like autism, PWS is a spectrum disorder and symptoms can range from mild to severe and may change throughout the person's lifetime. Various organ systems are affected.

Traditionally, PWS was diagnosed by clinical presentation. Currently, the syndrome is diagnosed through genetic testing; testing is recommended for newborns with pronounced hypotonia. Early diagnosis of PWS allows for early intervention and the early prescription of growth hormone. Daily recombinant growth hormone (GH) injections are indicated for children with PWS. GH supports linear growth and increased muscle mass, and may lessen food preoccupation and weight gain.

The mainstay of diagnosis is genetic testing, specifically DNA-based methylation testing to detect the absence of the paternally contributed PWS/AS region on chromosome 15q11-q13. Such testing detects over 97% of cases. Methylation-specific testing is important to confirm the diagnosis of PWS in all individuals, but especially those who are too young to manifest sufficient features to make the diagnosis on clinical grounds or in those individuals who have atypical findings.

PWS is often misdiagnosed as other syndromes due to many in the medical community's unfamiliarity with it.[21] Sometimes it is misdiagnosed as Down syndrome, simply because of the relative frequency of Down syndrome compared to PWS.[21]

Treatment

PWS has no cure; several treatments are available to lessen the condition's symptoms. During infancy, subjects should undergo therapies to improve muscle strength. Speech and occupational therapy are also indicated. During the school years, children benefit from a highly structured learning environment and extra help. The largest problem associated with the syndrome is severe obesity. Access to food must be strictly supervised and limited, usually by installing locks on all food-storage places including refrigerators.[20] Physical activity in individuals with PWS for all ages is needed to optimize strength and promote a healthy lifestyle.[13]

Prescription of daily recombinant GH injections are indicated for children with PWS. GH supports linear growth and increased muscle mass, and may lessen food preoccupation and weight gain.[39][40][41]

Because of severe obesity, obstructive sleep apnea is a common sequela, and a positive airway pressure machine is often needed. A person who has been diagnosed with PWS may have to undergo surgical procedures. One surgery that has proven to be unsuccessful for treating the obesity is gastric bypass.[42]

Behavior and psychiatric problems should be detected early for the best results. These issues are best when treated with parental education and training. Sometimes medication is introduced, as well. Serotonin agonists have been most effective in lessening temper tantrums and improving compulsivity.[13]

Epidemiology

PWS affects one in 10,000 to one in 25,000 newborns.[38] More than 400,000 people live with PWS.[43]

Society and culture

%2C_de_Juan_Carre%C3%B1o_de_Miranda..jpg)

Despite its rarity, PWS has been often referenced in popular culture, partly due to curiosity surrounding the insatiable appetite and obesity that are symptoms.

The syndrome has been depicted and documented several times in television. A fictional individual with PWS featured in the episode "Dog Eat Dog" of the television series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, which aired in the US on 24 November 2005.[45] In July 2007 Channel 4 aired a 2006 documentary called Can't Stop Eating, surrounding the everyday lives of two people with PWS, Joe and Tamara.[46] In 2010 episode of Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, Sheryl Crow helped Ty Pennington rebuild a home for a family whose youngest son, Ethan Starkweather, was living with the syndrome.[47] In a 2012 episode of Mystery Diagnosis on the Discovery Health channel, Conor Heybach, who has Prader–Willi syndrome, shared how he was diagnosed with it.[48]

See also

References

- "Prader-Labhardt-Willi syndrome". Whonamedit?. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- Cortés M, F; Alliende R, MA; Barrios R, A; Curotto L, B; Santa María V, L; Barraza O, X; Troncoso A, L; Mellado S, C; Pardo V, R (January 2005). "[Clinical, genetic and molecular features in 45 patients with Prader-Willi syndrome]". Revista Médica de Chile. 133 (1): 33–41. doi:10.4067/s0034-98872005000100005. PMID 15768148.

- "Prader-Willi syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. June 2014. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Is there a cure for Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)?". NICHD. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- Teitelbaum, Jonathan E. (2007). In a Page: Pediatrics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 330. ISBN 9780781770453.

- "What are the treatments for Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)?". NICHD. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- "How many people are affected/at risk for Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)?". NICHD. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- "Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS): Other FAQs". NICHD. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 27, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Angelman syndrome". Genetic Home Reference. May 2015. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- Mia, Md Mohan (2016). Classical and Molecular Genetics. American Academic Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-63181-776-2. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017.

- Jorde, Lynn B.; Carey, John C.; Bamshad, Michael J. (2015). Medical Genetics (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-323-18837-1.

- "Mayo Clinic, Diseases and Conditions". Prader-Willi Syndrome, Symptoms and Causes. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Cassidy, Suzanne B; Driscoll, Daniel J (September 10, 2008). "Prader–Willi syndrome". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.165. PMC 2985966. PMID 18781185.

- Curfs LM, Fryns JP (1992). "Prader-Willi syndrome: a review with special attention to the cognitive and behavioral profile". Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 28 (1): 99–104. PMID 1340242.

- Cassidy SB (1997). "Prader-Willi syndrome". Journal of Medical Genetics. 34 (11): 917–23. doi:10.1136/jmg.34.11.917. PMC 1051120. PMID 9391886.

- Udwin O (November 1998). "Prader-Willi syndrome: Psychological and behavioural characteristics". Contact a Family. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- Holm VA, Cassidy SB, Butler MG, Hanchett JM, Greenswag LR, Whitman BY, Greenberg F (1993). "Prader-Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria". Pediatrics. 91 (2): 398–402. PMC 6714046. PMID 8424017.

- Whittington J, Holland A, Webb T, Butler J, Clarke D, Boer H (February 2004). "Cognitive abilities and genotype in a population-based sample of people with Prader-Willi syndrome". J Intellect Disabil Res. 48 (Pt 2): 172–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00556.x. PMID 14723659.

- Boer, H; Holland, A; Whittington, J; Butler, J; Webb, T; Clarke, D (January 12, 2002). "Psychotic illness in people with Prader Willi syndrome due to chromosome 15 maternal uniparental disomy". Lancet. 359 (9301): 135–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07340-3. PMID 11809260. S2CID 21083489.

- "What are the treatments for Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)?". Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Nordqvist, Christian (March 15, 2010). "What Is Prader-Willi Syndrome? What Causes Prader-Willi Syndrome?". Medical News Today. MediLexicon International. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- Cummings DE, Clement K, Purnell JQ, Vaisse C, Foster KE, Frayo RS, Schwartz MW, Basdevant A, Weigle DS (July 2002). "Elevated plasma ghrelin levels in Prader Willi syndrome". Nature Medicine. 8 (7): 643–4. doi:10.1038/nm0702-643. PMID 12091883. S2CID 5253679.

- Clark DJ, Boer H, Webb T (1995). "General and behavioural aspects of PWS: a review". Mental Health Research. 8 (195): 38–49.

- Cassidy SB, Devi A, Mukaida C (1994). "Aging in PWS: 232 patients over age 30 years". Proc. Greenwood Genetic Centre. 13: 102–3.

- Hered RW, Rogers S, Zang YF, Biglan AW (1988). "Ophthalmologic features of Prader-Willi syndrome". J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 25 (3): 145–50. PMID 3397859.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Prader-Willi Syndrome; PWS - 17627

- de los Santos T, Schweizer J, Rees CA, Francke U (November 2000). "Small evolutionarily conserved RNA, resembling C/D box small nucleolar RNA, is transcribed from PWCR1, a novel imprinted gene in the Prader-Willi deletion region, which is highly expressed in brain". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (5): 1067–82. doi:10.1086/303106. PMC 1288549. PMID 11007541.

- Cavaillé J, Buiting K, Kiefmann M, Lalande M, Brannan CI, Horsthemke B, Bachellerie JP, Brosius J, Hüttenhofer A (December 2000). "Identification of brain-specific and imprinted small nucleolar RNA genes exhibiting an unusual genomic organization". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (26): 14311–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9714311C. doi:10.1073/pnas.250426397. PMC 18915. PMID 11106375.

- "Prader-Willi Syndrome - MeSH - NCBI." National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. November 1, 2016. <"Prader-Willi Syndrome - MeSH - NCBI". Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.>.

- Buiting, K; Saitoh, S; Gross, S; Dittrich, B; Schwartz, S; Nicholls, RD; Horsthemke, B (April 1995). "Inherited microdeletions in the Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes define an imprinting centre on human chromosome 15". Nature Genetics. 9 (4): 395–400. doi:10.1038/ng0495-395. PMID 7795645. S2CID 7184110.

- "Major breakthrough in understanding Prader-Willi syndrome, a parental imprinting disorder". Medicalxpress.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Runte M, Varon R, Horn D, Horsthemke B, Buiting K (2005). "Exclusion of the C/D box snoRNA gene cluster HBII-52 from a major role in Prader-Willi syndrome". Hum Genet. 116 (3): 228–30. doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1219-2. PMID 15565282. S2CID 23190709.

- Skryabin BV, Gubar LV, Seeger B, Pfeiffer J, Handel S, Robeck T, Karpova E, Rozhdestvensky TS, Brosius J (2007). "Deletion of the MBII-85 snoRNA gene cluster in mice results in postnatal growth retardation". PLOS Genet. 3 (12): e235. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030235. PMC 2323313. PMID 18166085.

- Sahoo T, del Gaudio D, German JR, Shinawi M, Peters SU, Person RE, Garnica A, Cheung SW, Beaudet AL (2008). "Prader-Willi phenotype caused by paternal deficiency for the HBII-85 C/D box small nucleolar RNA cluster". Nat Genet. 40 (6): 719–21. doi:10.1038/ng.158. PMC 2705197. PMID 18500341.

- Ding F, Li HH, Zhang S, Solomon NM, Camper SA, Cohen P, Francke U (March 2008). "SnoRNA Snord116 (Pwcr1/MBII-85) deletion causes growth deficiency and hyperphagia in mice". PLOS ONE. 3 (3): e1709. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1709D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001709. PMC 2248623. PMID 18320030.

- Ding F, Prints Y, Dhar MS, Johnson DK, Garnacho-Montero C, Nicholls RD, Francke U (2005). "Lack of Pwcr1/MBII-85 snoRNA is critical for neonatal lethality in Prader-Willi syndrome mouse models". Mamm Genome. 16 (6): 424–31. doi:10.1007/s00335-005-2460-2. PMID 16075369. S2CID 12256515.

- de Smith AJ, Purmann C, Walters RG, Ellis RJ, Holder SE, Van Haelst MM, Brady AF, Fairbrother UL, Dattani M, Keogh JM, Henning E, Yeo GS, O'Rahilly S, Froguel P, Farooqi IS, Blakemore AI (June 2009). "A Deletion of the HBII-85 Class of Small Nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) is Associated with Hyperphagia, Obesity and Hypogonadism". Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 (17): 3257–65. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp263. PMC 2722987. PMID 19498035.

- Killeen, Anthony A. (2004). "Genetic Inheritance". Principles of Molecular Pathology. Humana Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-58829-085-4. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014.

- Davies PS, Evans S, Broomhead S, Clough H, Day JM, Laidlaw A, Barnes ND (May 1998). "Effect of growth hormone on height, weight, and body composition in Prader-Willi syndrome". Arch. Dis. Child. 78 (5): 474–6. doi:10.1136/adc.78.5.474. PMC 1717576. PMID 9659098.

- Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, Allen DB (April 2002). "Benefits of long-term GH therapy in Prader-Willi syndrome: a 4-year study". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (4): 1581–5. doi:10.1210/jc.87.4.1581. PMID 11932286.

- Höybye C, Hilding A, Jacobsson H, Thorén M (May 2003). "Growth hormone treatment improves body composition in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome". Clin. Endocrinol. 58 (5): 653–61. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01769.x. PMID 12699450.

- Scheimann, AO; Butler, MG; Gourash, L; Cuffari, C; Klish, W (January 2008). "Critical analysis of bariatric procedures in Prader-Willi syndrome". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 46 (1): 80–3. doi:10.1097/01.mpg.0000304458.30294.31. PMC 6815229. PMID 18162838.

- Tweed, Katherine (September 2009). "Shawn Cooper Struggles with Prader Willi Syndrome". AOL Health. Archived from the original on September 9, 2009. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- Mary Jones. "Case Study: Cataplexy and SOREMPs Without Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Prader Willi Syndrome. Is This the Beginning of Narcolepsy in a Five Year Old?". European Society of Sleep Technologists. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- "Dog Eat Dog". Csifiles.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- "Can't Stop Eating". Channel4.com. 2006. Archived from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- "Extreme Makeover: Home Edition Articles on AOL TV". Aoltv.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prader-Willi syndrome. |