Hyères

Hyères (French pronunciation: [jɛːʁ]), Provençal Occitan: Ieras in classical norm, or Iero in Mistralian norm) is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

Hyères | |

|---|---|

A hillside view of the town | |

Coat of arms | |

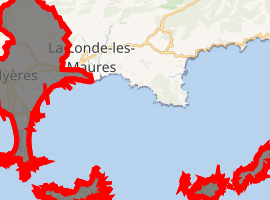

Location of Hyères

| |

Hyères  Hyères | |

| Coordinates: 43°07′12″N 6°07′54″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Var |

| Arrondissement | Toulon |

| Canton | Hyères and La Crau |

| Intercommunality | Métropole Toulon Provence Méditerranée |

| Area 1 | 132.28 km2 (51.07 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 55,588 |

| • Density | 420/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 83069 /83400 |

| Elevation | 0–325 m (0–1,066 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

The old town lies 4 km (2.5 mi) from the sea clustered around the Castle of Saint Bernard, which is set on a hill. Between the old town and the sea lies the pine-covered hill of Costebelle, which overlooks the peninsula of Giens. Hyères is the oldest resort on the French Riviera.[2]

History

Hellenic Olbia

The Hellenic city of Olbia[3] was refounded on the Phoenician settlement that dated to the fourth century BC; Olbia is mentioned by the geographer Strabo (IV.1.5) as a city of the Massiliotes that was fortified "against the tribe of the Salyes and against those Ligures who live in the Alps". Greek and Roman antiquities have been found in the area. The first reference to the town dates from 964.[4]

Middle Ages

Originally a possession of the Viscount of Marseilles, it was later transferred to Charles of Anjou. Louis IX King of France (often known as "St Louis") landed at Hyères in 1254 when returning from the crusades.[4]

A commandry of the Knights Templar was based at the town in the 12th century, outside the town walls. The remaining remnant is the tower Saint-Blaise.[5]

20th century

After defecting from Soviet intelligence in 1937, Walter Krivitsky hid in Hyères (one of the farthest points in France from his operational base in Paris).[6]

World War II

As part of Operation Dragoon on 15 August 1944, the First Special Service Force came ashore off the coast of Hyères to take the islands of Port-Cros and Levant. The small German garrisons offered little resistance and the whole eastern part of Port-Cros was secured by 06:30. All fighting was over on Levant by the evening, but, on Port-Cros, the Germans withdrew into old thick-walled forts. It was only when naval guns were brought to bear that they realised that further resistance was useless.[7]

An intense naval barrage on 18 August 1944 heralded the next phase of the operation—the assault on the largest of the Hyères islands, Porquerolles. French forces—naval units and colonial formations, including Senegalese infantry—became involved on 22 August and subsequently occupied the island. A US-Canadian Special Forces landing at the eastern end of Porquerolles took large numbers of prisoners, the Germans preferring not to surrender to the Senegalese.[8]

Geography

Its position facing the Mediterranean to the south makes it popular with tourists in the winter and makes it ideal for the cultivation of palm trees. About 100,000 trees are exported from the area each year. As a result, the town is frequently referred to as Hyères-les-Palmiers (palmiers meaning palm trees).

The three islands of the Îles d'Hyères (namely, Porquerolles, Port-Cros, and the Île du Levant) are just offshore. Porquerolles and Port-Cros form the Port-Cros National Park.

The commune has a land area of 132.38 square kilometres (51.11 sq mi).

Climate

The city of Hyères has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen:Csa) and it's one of the warmest cities in France. Winters are relatively mild and summers are hot, with maximum temperatures often surpassing 30 °C (86 °F). It is also one of the driest cities in France, with barely 57 rainy days per year and almost rainless summers.

| Climate data for Hyères (1981–2010 averages, extremes 1959–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.5 (97.7) |

42.3 (108.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.5 (97.7) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

42.3 (108.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.0 (12.2) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 79.1 (3.11) |

52.6 (2.07) |

40.7 (1.60) |

60.4 (2.38) |

40.6 (1.60) |

35.8 (1.41) |

7.5 (0.30) |

19.3 (0.76) |

55.4 (2.18) |

105.4 (4.15) |

81.3 (3.20) |

73.9 (2.91) |

652.0 (25.67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.9 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 56.8 |

| Average snowy days | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Source: Meteo France[9][10][11] | |||||||||||||

British and Americans in Hyères, 18th to early 20th centuries

Lord Albemarle, the British ambassador, stayed in Hyères during the winter 1767-1768, and Prince Augustus, sixth son of George III, stayed there in the winter of 1788 for health reasons. The English agronomist Arthur Young visited Hyères on the advice of Lady Craven on 10 September 1789. He mentioned the many British living there in his book Travels in France.[4] The London-born and Eton-educated Anglo-Grison Charles de Salis died in Hyères in July 1781, aged 45, and was buried in the Convent des Cordeliers.

In 1791, Charlotte Turner Smith published her novel Celestina, which is set in Hyères.[4] During the period of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the British left the area, but they returned after 1815. Joseph Conrad, who lived for a while in Hyères, wrote his novel, The Rover, which is set in Hyères, during those years.

William FitzRoy, 6th Duke of Grafton spent the winter and spring each year at Hyères because he and his wife suffered from ill health. Edwin Lee M.D. published in 1857 a book on the virtues of the climate of Hyères for the recovery of pulmonary consumption[12] and in November 1880 Adolphe Smith first published The Garden of Hyères, which is still in print, (see Hachette edition of 2012).[13]

In 1883, Robert Louis Stevenson came to Hyères and for about two years lived first at the Grand Hotel (the building still stands in the Avenue des Iles d'Or), and then in a chalet called Solitude in the present rue Victor-Basch.[4] He wrote then: "That spot our garden and our view are sub-celestial. I sing daily with Bunian, that great bard. I dwell next door to Heaven!" In later years, he wrote from his retreat in Valima: "Happy (said I); I was only happy once; that was at Hyères".

In 1884, Elisabeth Douglas, daughter of Alfred, Lord Douglas, had a small "cottage", as she called it, built on the Costebelle hill by the architect Thomas Donaldson, who used to spend his winters in Hyères during those years.

The British presence culminated in the winter of 1892 (21 March - 25 April) when Queen Victoria came for a stay of three weeks[14] at the Albion Hotel. At that time, the British influence was so strong that shop signs were in both French and English. There was an English butcher, a chemist, two banks, and two golf courses. There were also two English churches (plus one at the Grand Hôtel in Costebelle), whose buildings still exist: All Saint's Church at Costebelle and Saint Paul's English Church, Avenue Beauregard.

Some signs of this English presence have vanished, like the small dell in the cemetery where there were once some hundred graves. Some of these, such as those of Lord Arthur Somerset or Richard John Meade, bore testimony to the aristocratic nature of the community. Other vestiges remain, like the fountain near the new public library in a square shaded by a plane tree. The inscription reads: "In loving memory of Marianne Stewart who died on 18 August 1900. She laboured many years in the cause of mercy to animals. Her last wish was that a drinking fountain should be set up for them in Hyères".

Many wounded British soldiers were sent to the town to convalesce during World War I.

The American novelist Edith Wharton wintered in Hyères annually from 1919 until her death in 1937. The garden of her villa, Castel Sainte-Claire, is open to the public. The villa previously belonged to Olivier Voutier, a French naval officer, whose grave is in the garden. It was Voutier who discovered the Venus de Milo in 1820 on the Aegean island of Milos.[4]

Transportation

The railway station Gare d'Hyères offers connections with Toulon, Marseille, Paris, and several regional destinations.

The airport, which is known officially as the Toulon-Hyères International Airport, is 4 km (2.5 mi) to the southeast of the town centre, on a sandy plain close to the seashore. The area was first used by private aircraft at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1920, after the marsh had been drained, French naval aircraft used the field, and, in 1925, it became an official base of the French Fleet Air Arm (Aéronavale). It has been a commercial airport since 1966, but the navy maintains a significant facility for helicopters and fixed wing aircraft within the perimeter.[15]

There are currently (2009) scheduled flights to and from Stockholm, Bristol, Ajaccio, Paris, London, Brest, Brussels, and Rotterdam.[16]

Personalities

Hyères was the birthplace of Jean Baptiste Massillon (1663–1742), churchman and preacher as well as Marius Gueit (1808– 1862), blind composer, organist and cellist.

The author Jean-Marie-Edmond Sabran (1908–1994), who wrote under the pseudonyms Paul Berna (children's fiction), Bernard Deleuse and Paul Gerradwas (adult fiction), and Joel Audrenn (crime novels), was born in Hyères as well as François Coupry (born 1947), winner of the 1970 edition of the Prix des Deux Magots.

The French historian Jules Michelet frequently spent the winter at Hyères. He died from a heart attack at Hyères on 9 February 1874. He was interred at Hyères. Following his widow's request, a Paris court granted permission for his body to be exhumed on 13 May 1876.

Twin towns

Hyères is twinned with Rottweil, Germany and with Koekelberg, Belgium.

Culture

Hyères is home to the Hyères International Fashion and Photography Festival, a huge fashion and art photography event that has taken place annually at the end of April since 1985. This festival was among the first to recognize the talents of Viktor & Rolf.

The city also plays host to the annual MIDI French Riviera Festival in July, a music festival now into its sixth episode. 2010's MIDI saw around 15 acts play at the Villa Noailles complex and brought the new 'MIDI Night' event to Almanarre Beach in the early hours of Sunday morning.

See also

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Hyeres holidays self catering and short breaks – Book self-catering holidays in Hyeres". Cotedazurcollection.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-06-07. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- For other Greek cities bearing this name, see Olbia.

- Hyères les palmiers – plus de 2000 ans d’histoire, 45330 Malesherbes: Image et Mémoire de Hyères et Centre de Culture et de la Documentation provençales, 1993, ISBN 2-9507432-0-XCS1 maint: location (link)

- Hyères, Pinterrest, accessed 7 August 2013

- Krivitsky, Walter G. (1939). In Stalin's Secret Service: An Exposé of Russia's Secret Policies by the Former Chief of the Soviet Intelligence in Western Europe. New York: Harper Brothers. pp. 290, 294. LCCN 40027004. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- Pallud, Jean-Paul (2000), "The Riviera Landings", After the Battle, Battle of Britain Prints International (110)

- Borel, Vincent (1998), Hyères et sa région dans la guerre de 1939 - 1945, Marly-le-Roi: Editions Champflour, ISBN 2-87655-038-5

- "Données climatiques de la station de Hyères" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- "Climat Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- "Hyeres (83)" (PDF). Fiche Climatologique: Statistiques 1981–2010 et records (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- Notices sur Hyères et Cannes. Edwin Lee, M.D. 1857

- Smith, Adolphe (November 1880), The Garden of Hyères - A Description of the Most Southern Port on the French Riviera, Carnarvon: The author

- London Illustrated News 19 March 1892

- BAN Hyères, archived from the original on 2008-01-09, retrieved 2007-08-14

- CCIV Toulon airport, retrieved 2009-09-11

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyères. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hyères. |

- Free download of The Garden of Hyères on the site of the National French Library

- Official Tourist Office

- Official website (in French)

- Indiscretions from Hyères Unofficial website (in French)

- VillaNoailles- the site of Villa Noailles, an avant-garde villa turned cultural center, home of the Hyères Fashion and Photography Festival, MIDI French Riviera Festival, Design Parade and other events.

- MIDI French Riviera Festival - MIDI Music Festival