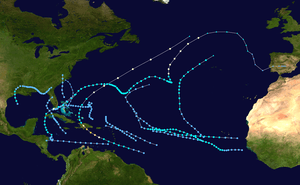

Hurricane Floyd (1987)

Hurricane Floyd was the only hurricane to make landfall in the United States in the 1987 Atlantic hurricane season. The final of seven tropical storms and three hurricanes, Floyd developed on October 9 just off the east coast of Nicaragua. After becoming a tropical storm, it moved northward and crossed western Cuba. An approaching cold front caused Floyd to turn unexpectedly to the northeast, and late on October 12 it attained hurricane status near the Florida Keys. It moved through southern Florida, spawning two tornadoes and leaving minor damage. The hurricane also produced rip tides that killed a person in southern Texas. Floyd maintained hurricane status for only 12 hours before the cold front imparted hostile conditions and caused weakening. It passed through the Bahamas before becoming extratropical and later dissipating on October 14.

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Floyd at peak intensity near the Florida Keys on October 12 | |

| Formed | October 9, 1987 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 13, 1987 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 75 mph (120 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 993 mbar (hPa); 29.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 reported |

| Damage | $500,000 (1997 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cuba, Florida and The Bahamas |

| Part of the 1987 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

The origins of Hurricane Floyd were from a low pressure area in the Gulf of Honduras on October 5. Over the subsequent few days, it drifted eastward and later southward to a position off the east coast of Nicaragua. On October 9, a Hurricane Hunters flight confirmed the development of an organized circulation, which indicated that Tropical Depression Thirteen had developed. After continuing a southward drift, the depression turned to the north and later northwest due to a building ridge to its east. With an anticyclone aloft, the depression gradually organized, intensifying into Tropical Storm Floyd on October 10.[1]

After reaching tropical storm status, Floyd accelerated to the north in the western Caribbean Sea, due to an approaching cold front. Steadily intensifying, the storm moved over extreme western Cuba early on October 12.[1] Initially it was forecast to make landfall between Naples and Fort Myers, Florida. Unexpectedly the storm turned sharply northeastward into the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.[2] Based on reports from the Hurricane Hunters, Floyd briefly attained hurricane status on October 12. Around the same time, the nearby cold front spawned a low pressure area that cut off the hurricane's inflow. While moving through the Florida Keys, Floyd became the only hurricane to affect the United States that year. However, its convection was rapidly decreasing over the center due to the front, and shortly thereafter Floyd weakened to tropical storm status. The circulation became nearly impossible to track on satellite imagery,[1] although surface observations indicated it passed just south of Miami, Florida. The storm underwent extratropical transition as it weakened over the Bahamas, and Floyd was no longer a tropical cyclone by late on October 18. The circulation dissipated within the cold front early the next day.[3]

Preparations and impact

Around when Floyd first attained tropical storm status, a tropical storm warning was issued for the Swan Islands as well as Grand Cayman. Shortly thereafter, a tropical storm warning and hurricane watch was issued for the northeast Yucatán Peninsula before the storm dropped heavy rainfall along the coast.[4][5] A tropical storm warning and hurricane watch were also issued for Cuba west of Havana.[4] In preparation for the storm, Cuban officials in Pinar del Río Province evacuated 100,000 people, as well as 40,000 head of cattle. In addition, international flights were canceled for a day during Floyd's passage.[6] Despite passing over western Cuba as a tropical storm, Floyd left no serious damage or fatalities in the country.[2]

When Floyd was a tropical storm located over Cuba, the National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane warning for the Florida Keys as well as the southwest Florida coast to Venice. It was the first warning in the state related to the storm, and was issued due to the anticipated intensification to hurricane status as well as short notice.[2] A tropical storm watch, and later warning, was issued for eastern Florida.[7] After the track became more easterly, a hurricane warning was issued for southeastern Florida,[2] as well as the northwestern Bahamas.[7] Officials in southern Florida closed schools due to the storm,[6] and a few flights were canceled at Miami International Airport. Roughly 100 F-4 and F16 fighter jets were transported out of Homestead Air Force Base to safer facilities. The American Red Cross opened 55 shelters in 10 Florida counties, housing about 2,000 people at some point, primarily in Lee County.[8] People in the hurricane's path prepared by purchasing supplies from supermarkets, gassing up their vehicles, and securing loose outside items.[9]

Floyd was the first named storm to strike southern Florida since Hurricane Bob in 1985.[10] While passing south of Florida, Floyd produced its strongest winds over water away and from land. The strongest wind in the Florida Keys was 59 mph (94 km/h) at Duck Key, although wind gusts were stronger. The Air Force station on Cudjoe Key reported an unofficial gust of 92 mph (152 km/h). Rainfall directly from Floyd's rainbands produced minimal rainfall less than 1 in (25 mm). However, the interaction between the hurricane and the approaching cold front produced much heavier rainfall.[3] Precipitation reached as far north as Daytona, peaking at 10.07 in (256 mm) in Fort Pierce.[11] While bypassing the Florida Keys, Floyd spawned a waterspout that moved ashore in Rock Harbor. It damaged a few boats and homes.[3] The hurricane produced rip tides as far west as the Texas coast, killing one person along South Padre Island.[12]

Across southern Florida, the hurricane left minor damage of around $500,000 (1987 USD),[13] largely due to downed trees and power lines, as well as minor crop damage in Dade County.[2] The rainfall flooded roads in southern Florida, which caused several vehicles to fail on the Florida Turnpike.[6] After affecting Florida, Floyd caused minor wind damage in the Bahamas.[2] In the country, the highest reported gust was 48 mph (77 km/h) at Freeport, Grand Bahama. Freeport International Airport reported sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) from the remnants of Floyd.[14]

On October 15, British weather forecaster Michael Fish stated on BBC, "Earlier on today, apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she heard there was a hurricane on the way; well, if you're watching, don't worry, there isn't, but having said that, actually, the weather will become very windy, but most of the strong winds, incidentally, will be down over Spain and across into France." That same day, a weather system developing over the Bay of Biscay struck South East England as one of the worst storms in the United Kingdom in three centuries.[15] Though technically not a hurricane, the United Kingdom experienced wind gusts up to 120 mph (195 km/h).[16] Fish was criticized for incorrectly forecasting the storm and later claimed he was referring to Hurricane Floyd, but neglected to mention Florida.[17]

See also

- Other storms of the same name

References

- Gilbert C. Clark (1987-10-27). "Hurricane Floyd Preliminary Report (Page 1)" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- Gilbert C. Clark (1987-10-27). "Hurricane Floyd Preliminary Report (Page 3)" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Gilbert C. Clark (1987-10-27). "Hurricane Floyd Preliminary Report (Page 2)" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- Gilbert C. Clark (1987-10-27). "Table 3. Watches and Warnings for Hurricane Floyd, October 1987" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Staff Writer (1987-10-11). "Storms Cause Heavy Rains". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Staff Writer (1987-10-12). "Storm gains strength, nears Florida". The Dispatch. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Gilbert C. Clark (1987-10-27). "Table 3. Watches and Warnings for Hurricane Floyd, October 1987 (page 2)" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Richard Cole (1987-10-13). "Floyd Brushes Over Keys, Miami, Moves Out to Sea". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Mark Zaloudek (1987-10-13). "Floyd Misses Gulf Coast - Which Doesn't Miss Floyd". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Staff Writer (1987-10-13). "Floyd rolls over Florida". Star-News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- David Roth (2005-09-25). "Hurricane Floyd - October 10-13, 1987". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Staff Writer (1987-10-13). "Hurricane Floyd causes riptide along Texas coast". The Bonham Daily Favorite. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- Robert A. Case and Harold Gerrish (April 1988). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1987" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 116. Bibcode:1988MWRv..116..939C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1988)116<0939:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- Staff Writer (1987-10-14). "Floyd Nicks Bahamas, Fades Into Oblivion". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- Patrick Scott and Ashley Kirk (2017-10-16). "Ophelia wind speed forecast: How likely are you to get hurricane-force gales?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- "The Great Storm of 1987". Met Office. 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- "Michael Fish and the 1987 Storm". BBC. 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-10-01. Retrieved 2019-02-07.