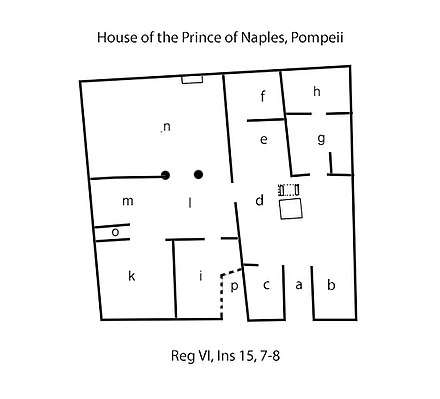

House of the Prince of Naples

The House of the Prince of Naples is a Roman townhouse located in Region VI, Insula XV, entrances 7 and 8 in the archaeological site of Pompeii near Naples, Italy. The structure is so named because the Prince and Princess of Naples attended a ceremonial excavation of selected rooms there on March 22, 1898. The house is painted throughout in the Pompeian Fourth Style and is valued by scholars because its decoration is all of a single style and single period, unlike many surviving Roman structures that are found to be a hodgepodge of styles from different periods.[1]

| House of the Prince of Naples | |

|---|---|

Casa del Principe di Napoli | |

Atrium of the House of the Prince of Naples in Pompeii watercolor by Luigi Bazzani | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | archaeological remains |

| Architectural style | Roman fauces-atrium-tablinum matrix |

| Classification | Townhouse |

| Location | Pompeii, Roman Empire |

| Address | VI, XV, 7.8, Viccolo dei Vetti, 80045 Pompei, Italy |

| Town or city | Pompei |

| Country | Italy |

| Coordinates | 40°45′07″N 14°29′04″E |

| Current tenants | 0 |

| Named for | Prince of Naples (1898) |

| Construction started | 2nd century BCE |

| Renovated | 1st century CE, 55 CE |

| Destroyed | 79 CE |

| Technical details | |

| Material | opus incertum, opus reticulatum |

| Known for | Pompeian Fourth Style Paintings |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 11 (lower floor) |

Initial excavation

The initial excavation began in October 1896 after the structure's entrances were discovered following the excavation of the expansive House of the Vettii. The excavation team entered through the fauces into the atrium and surrounding rooms and finds were reported in rooms (c), (d), and (n). The work continued until the end of December, 1896, with further finds discovered in (d), (n), (e), (g), and (l). Excavations did not resume until February, 1897, when the kitchen and two cubiculums were finally cleared. Then the garden was cleared on May 21. Excavations where artifacts were expected were reserved for a formal royal visit in the spring of 1898. At the official naming ceremonial excavation on March 22, 1898 rich finds were made in two cubiculums, the tablinum, the triclinium and the exedra. Another ceremonial excavation in front of the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar on March 29, 1898, resulted in finds in the pantry and the room accessed through entrance 7 that housed a staircase to the upper floor, at which point the excavation was officially ended. Protective roofs were erected, then in 1972, the ground floor was completely covered after razing much of the ancient walls of the upper story so flat concrete ceilings could be installed and tiled roofs constructed over the atrium and Porticus.[2]

Construction chronology

The house was determined by German archaeologists to have been originally constructed during the Limestone Age (3rd century BCE) due to the entrance consisting entirely of opus incertum with cruma and lava, rather than the late 2nd century BCE originally proposed by Italian excavators. German researchers also point to the limestone framework of the southern wall of the garden which also demonstrates the construction belonged to this earlier period. The absence of limestone posts in the dividing wall between the atrium and the portico indicates that partition was a subsequent modification.

The dwelling(s) fronted the Viccola dei Vetti and the spaces on either sides of their main entrances appear to have been initially involved in commercial activities. German archaeologists noted the presence of holes indicating the suspension of a canopy on the north section of the external facade.

Late 2nd century BCE

During the late 2nd century BCE, Pompeii experienced a major population expansion and the insulae of Region VI became dotted with establishments engaged in urban commerce.[3] Furthermore, the upper floor of this structure, demolished in the 1970s, above (a), (b), (c) (e), (f), (i),(k) and (l) is thought to have contained rooms that were possibly rented out as apartments.[4]

German archaeologists date the construction of the impluvium to the early 1st century BCE in part because of the surrounding floor pavement of punteggiato regolare, a signinum featuring spaced travertine tesserae used widely in Pompeii beginning about 100 BCE. This improvement is thought to have been part of an overall renovation of the northern portion of the structure at that time.[5]

This activity may have been initiated to repair widespread damage and reflect a possible change of ownership that coincided with the aftermath of the Social War. Pompeii was one of the Campanian cities that rebelled against Rome in this conflict. In 89, BCE, the general, and later dictator, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, laid siege to Pompeii, bombarding Region VI's Porta Ercolano with his artillery, as evidenced by impact craters from thousands of sling bullets and ballistae bolts still visible on the ancient city wall.[3]

The nearly 4 foot-square impluvium is slightly south of the entrance axis to make it parallel to the room's south wall. A large marble table (cartibulum) supported by winged griffins found at the site has been placed at the impluvium's west edge since 1977.[6]

The off-centered axis of the impluvium served to focus the attention of visitors to the left side of the atrium where doorways to public reception rooms were located. This differentiation of space also guided attention away from the dimly illuminated utility areas of the house positioned in the right half of the atrium, the undecorated cubiculum of the ostiarius (a), with narrow stairs possibly leading to slave quarters on the upper floor, and the undecorated kitchen, latrine, and pantry (g) and (h). The pantry or storage room could have also been used as an eating area for the household slaves as well.

This off-centered arrangement reflects the influence of Greek architectural designs of Hellenistic houses and palaces where visiting males were purposefully directed away from female-inhabited interior spaces. But, where the Greeks used the arrangement to create privacy, the Romans used it to contrast space for invited as opposed to uninvited visitors.[1]

1st century CE

The next major renovation took place In the 1st half of the 1st century CE, when the passageway between the atrium accessed through entrance 8 and the space that would become the porticus in the structure accessed through entrance 7 was cut. A new partition with windows was constructed to separate the space southwest of the atrium, that would become the barrel-vaulted tablinium with adjoining barrel-vaulted cubiculum and provide views of the garden.[7]

This essentially created a "master suite" with views of the garden from both rooms and the provision of extra light augmented by the oculus in cubiculum (f). Scholars point to a persistent pattern in Roman architecture like this whereby a larger reception room, the tablinum in this case, is juxtaposed to a smaller room of suitable proportions for a bedroom, confirmed by the presence of a bed, denoting a hierarchy of intimacy where a guest could progress from the tablinum to the bedroom and, perhaps, to the bed recess itself.[1]

The windows also provided a framed view into the garden for visitors in the left half of the atrium and provided supplemental lighting. Both Cicero and Pliny the Elder, familiar with the precepts of famed Roman architect Vetruvius, discuss the importance of a framed view in Roman architecture not only for aesthetic purposes, but to demonstrate control over raw nature, and even modest homeowners would have been aware of these architectural strategies.[8]

The new passageway also provided more efficient access from the kitchen to the repurposed large triclinium and, subsequently, the new exedra as well.

The space that would become the triclinium was enclosed and an east–west barrel vault was suspended from the ceiling. The east wall was constructed with diamond-shaped limestone opus reticulatum, which in Pompeii is mostly post-Augustan.[9]

For the owners of the House of the Prince of Naples to repurpose what would have been prime commercial space along the Viccolo dei Vetti to domestic use would indicate a wealthier individual than previous occupants now owned the property. The new owner was putting aside economic space in order to generate social capital.[3]

If the new owner was, in fact, a physician, as indicated by finds of surgical instruments, his economic interests would have probably been better served by gaining patients with elevated social status.

A new partition forming the triclinium's north wall enclosed an adjoining room accessed through entrance 7 that contained a stairway to the upper floor. Columns were added between the garden and the rest of the space previously accessed through entrance 7.[10]

An east-west barrel vault was also added to cubiculum (c) and tablinum (e) and a north–south barrel vault was added to cubiculum (f) as well. The oculus in cubiculum (f), providing additional lighting to that space, may have been installed at this time, too.[11]

About 55 CE

In about 55 CE, based on painting style and the slight relocation of one of the portico's columns, the exedra with north–south barrel vault was constructed against the south wall of the porticus. Its east wall enclosed a small apotheca (space for a cabinet) between the exedra and the triclinium.[12]

After the major quake in 62 CE, new plastering is in evidence on the south wall of the triclinium, the west wall of the porticus, the north and south walls of cubiculum (c), the end walls of the fauces, and around the lararium in the garden. Also, at some point after the quake, the large door opening to the street on the east wall of room (i) was closed off as well with incertum composed of various materials, probably earthquake debris.[11]

Decoration and finds

Fauces (b)

The Fauces is paved with gray signinum with a net of rectangularly laid rows of white tesserae. There are two dark ocher-colored pilasters that were repaired, possibly due to the quake of 62 CE. The space includes the remains of a figurative picture thought by some scholars to have been Priapus or some similar guardian figure. The socle, painted black, is divided by yellow lines with yellow candelabra, with a red main zone and white upper zone. Cubes outlined with gray and red are painted in the white upper zone to imitate masonry, a decorative motif carried over from the First Style.[13]

Atrium (d)

The atrium, like the fauces has a black socle topped with a red main zone and white upper zone painted with three rows of rectangles outlined in gray and red. The red main zone is defined by narrow green bands with light green border lines and a filigree border with a simple bud pattern applied in ocher. Floating emblems include dancing swans and other birds thought to be peacocks.

In the atrium, excavators found a bronze basin with two handles terminating in the form of the heads of geese, another wide-mouthed bronze basin with two movable handles, a bronze bucket with a movable handle, a circular box with a hinged lid, a bronze fibula, a saucepan with protruding lip and circular handle, another large bucket with movable handle terminating in upturned goose heads with a fixed ring for hanging in the center, and two inscribed terracotta amphora.[6] A large bronze bucket of this type was most often used to mix wine with water in the kitchen area before serving. It was then transferred to a pitcher for pouring the watered wine into a cup or glass.

Cubiculum (c)

The black socle in this room is speckled with red and ochre to simulate marbling and is separated from the white main zone by an ochre stripe. The red-framed white main zone is divided by black vertical lines with red inner frames into panels with floating emblems of dancing swans and jumping goats. There is a window on the east wall that extends into the upper zone to provide supplemental lighting. There is a recently installed bed niche in the north wall where the gray signinum floor pavement had not yet been repaired. Three holes, two in the north wall and one in the western half of the side wall are suspected "robber" holes that were filled in by conservators to prevent further access.

A human skull and partial skeleton was found in the room along with a bronze surgical instrument, a herm with a feminine head and phallus in relief (Aphroditus), a small bell, a piece of bone worked on a lathe with a movable hook at the top, a spindle mold, and two pyramid-shaped weights. A fragmented tile with Oscan brand was also recovered.[14]

Late 20th century German scholars speculated the skeleton is probably the remains of a looter killed by falling debris. However, the presence of a surgical instrument, the apotropaic Aphroditus herm, and the bell coupled with the discovery of other surgical instruments at the site point to the possibility that the individual may have been a patient being treated by a resident physician.

Cubiculum (a)

All walls were plastered with rough black sand. The north wall above the west to east facing steps leading to the upper floor was plastered in a fine pale pink mixture. This room is thought to have been the bedroom of the ostiarius (doorman) and, perhaps, his family. The room contained a bronze candelabrum in the shape of a three-footed tree supported by three twigs. Excavators also found an as (coin) minted by Tiberius, three asses minted by Nero, and a dupondius minted by Vespasian. Additional finds included a bronze perforated cylinder, a lead pyramidal weight, a terracotta urceo (a jug often used for garum) a jar without handles, a lamp with a fragmented handle, a saucer, and a glass bottle with a large neck.[15]

Kitchen with latrine (g)

The remains of a stove were found in the northwest corner of this space with a large round-arched storage niche above it and a latrine was identified in the northeast corner. Originally, there was a doorway to the space that would become the tablinum, but at some point it was bricked up. There was also the remains of a wooden staircase to the upper floor along the south wall. The only wall finish remaining is unpainted reddish plaster.

Finds reported in this space include two unguentaria, a small conical-shaped bottle, a bottle with a spherical belly, and a small glass cup. Bronze items included a two-clasp padlock, a twisted physician's scalpel with iron blade and olive leaf-shaped handle, a boss supported by a moving ring, and a rectangular lock shield. Excavators also found a terracotta vessel with handle and bulging belly, a cup-shaped vase with two handles and an amphora.[15]

Pantry (h)

This storage area had only the remains of coarse plaster on the walls. Finds included an elliptical bronze figure-shaped basin, two bronze casseroles with perforated handles, a bronze base with a handle terminating in swan heads and a mask in the fragmented bottom, another bronze basin without handles, a bronze clasp, a bronze hook, and a corroded as minted by Tiberius. Other finds included two terracotta procoes, a lagena with two handles, an amphora with two handles, a pignattino with a cover without handles, a fragmented saucepan, an imitation Arezzo pot (Arrentine ware), a saucer, a lamp with one luminello decorated with two dolphins and a rudder, a glass odorino, a crustacean shell, a fragmented iron ax and the bones of chickens and sheep.[16]

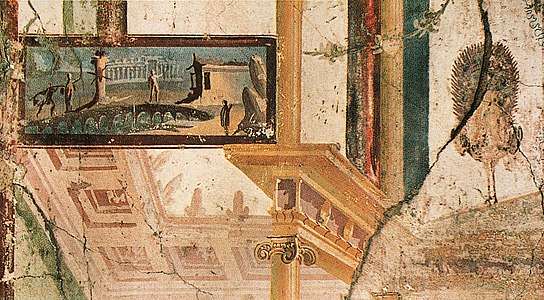

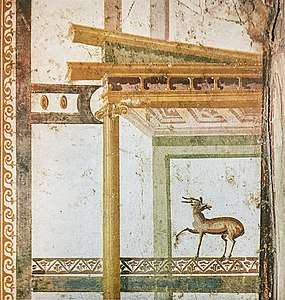

Tablinum (e)

Supports for stucco or wooden door panels were found on the south wall. The floor is paved with cocciopesto with travertine and lava skirts. The black socle and white main zone is divided into panels. Socle emblems include dancing swans, fluttering birds, and light and dark green leafy perennials and simply drawn lotus blossoms. The main fields include green leaf groups with red stems. Pinakes of a dog chasing a deer and a dog barking at a deer jumping to the right are painted on the north wall on either side of an ocher-colored architectural framework. In the white lunette of the west wall, a hippocamp and three dolphins are painted. In the center of the west wall, an architectural framework is painted with a left-facing griffin perched on the corner of its molding. A [[pinakes|pinax}} of two fish surrounded by other marine animals is painted in the right panel and a gold bucket or vessel with ladle is painted in the upper left panel above the doorway to cubiculum (f).

Finds include one cylindrical boiler without handles, another boiler with a base attached by two brackets in the form of unrecognizable animals turned upwards, a ring attached to a handle and corresponding lid suspended by a chain, another small ring attached to a key chain, a branded terracotta tile, a large, circular iron brazier, a bronze oleare with a detached handle, another oleare similar in size, and two door hinges.[17]

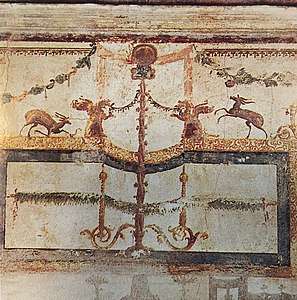

Cubiculum (f)

German archaeologists detected plaster edges of lost wooden door panels that could close the doorway between the tablinum and this cubiculum. Similar to the tablinum, this space has a black socle divided into panels with broadleafed green plants accented by yellow flower ornaments under the pilaster strips. The main zone is white divided into panels by dark red stripes. Panels are further detailed with filigree borders and floating emblems of opposing griffins, flying swans with heads turned back, dolphins, and jumping bucks. In the lunette of the alcove there is an outline of a peacock facing to the right and two round fruits.[18]

Porticus (l)

_(PD).jpg)

The floor pavement is coarse cocciopesto. The black socle, divided by white lines, is accented by simple diamonds enclosing four-petaled flowers. The main and upper zones are white framed by red stripes and separated from the socle with an ochre stripe. In the center of the north wall is a pilaster strip enclosing an ocher-shaded candelabra crowned by a frontal sphinx in dark red and blue-green. To the right of the pilaster strip is a red-framed pinax of two birds with cherries and mirabelles. The upper zone is divided by ornamental borders into symmetrical panels accented with floral tendrils. Border designs on what remains of the painting on the remaining walls have a different pattern from the north wall. A small preserved panel to the right of the doorway on the east wall contains a yellow dolphin.

Finds include a bronze bucket with movable handle, an oval frying pan with long ring-shaped handle, two fine handles with masks belonging to a boiler, a small pelvis (mortar and pestle) with the pestle in the form of a human finger, and a terracotta amphora. On the south side of the peristyle, excavators found a bronze circular frying pan, and an oval lid with movable handle.[19]

Secondary Room (i) with stairs (p) to upper floor

In the (p) portion of the space containing the stairs to the upper floor there is coarse plaster composed of black sand with little brick chippings. On the tongue wall and below the former flight of stairs. The same plaster is used on the remaining walls of (i) except on the south and east walls where a socle of fine reddish plaster was applied up to 1 3/4 m. high. On the east wall a pilaster next to entrance 7 is red and the inside of the adjoining partition wall is painted ocher.

Excavators found 54 rectangular counterweights in pyramidal form with holes to suspend them in the space under the staircase.[20]

Triclinium (k)

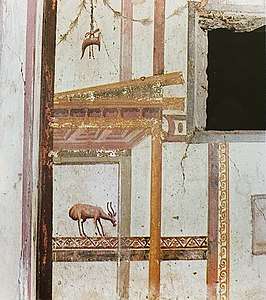

he floor pavement in this space is fine red-colored cocciopesto and in the center of the room is an opus sectile geometric mosaic composed of squares and triangles in different colored marbles. A stucco cornice has survived completely on the east wall but only in remnants on the north wall and is fragmented in the lunette of the barrel vault. A variety of filigree borders are used to define the three panels of the Fourth Style main zone wall paintings above a red-violet socle embellished with plants, birds and dolphins. Faux architectural structures draped in leaf garlands and animated with goats, birds and griffins, twisted candelabras, and small shrines enclosing plinths supporting Medusa heads, frontal sphinxes or Dionysian panthers with kantharos populate the upper zone.

On the east wall in the main zone, two aedicula containing a twisted candelabra capped with an ornate entablature topped with tragic masks flank a framed panel painting of either Paris and Helen or Adonis and Aphrodite with erotes standing between them.[21]

The original Italian excavators, August Mau and Antonio Sogliano, identified the couple as Paris and Helen. German archaeologist Volker Michael Strocka, analyzing the painting in his 1984 survey of the structure disagreed, pointing out that Paris was not wearing an oriental costume or is accompanied by any other attributes associated with Paris and there is no depiction in which Paris and Helen face each other in spite of numerous other examples of the couple elsewhere in Pompeii. Instead, Strocka said the young man's chlamys represents a hero's attire and points to the remnants of a spear shaft in the painting. He also points out that the woman as described by Sogliano as wearing a gold diadem, earrings, necklace, armillae and the usual golden cord that crosses her chest as in figures of Venus, closely resembles numerous descriptions of Aphrodite-Venus. He then concludes that since the young man lacks the usual weapons that normally accompany a depiction of Ares, the figure must be Adonis if the woman is Aphrodite. Strocka also mentions two post-Pompeian representations which, like this painting, depict Adonis on the left wearing a cloak and equipped with only a spear and Aphrodite on the right.[22]

In the upper zone of the east wall were three rectangular pinakes that have been completely destroyed although the original excavator Mau described the center one that was still intact at that time. He describes a night landscape with a partially covered bridge over a river with two barks with oarsmen. Two other men on the bridge appear to be helping the barks to land.

On the north wall of the triclinium, two fanciful aedicula with peacocks flank a framed panel painting of Perseus and Andromeda. Perseus, on the left, is heroically nude and grips the head of Medusa above the couple's heads so it reflects in a pool of water so Andromeda can look upon it safely.[21]

Hellenistic Perseus and Andromeda in Triclinium of Casa del Principe di Napoli Region VI

Hellenistic Perseus and Andromeda in Triclinium of Casa del Principe di Napoli Region VI Roman-style Perseus and Andromeda panel painting from the Casa della Saffo in Pompeii Region VI

Roman-style Perseus and Andromeda panel painting from the Casa della Saffo in Pompeii Region VI Roman-style Perseus and Andromeda panel painting from the Casa dei Capitelli Colorati in Pompeii Region VII

Roman-style Perseus and Andromeda panel painting from the Casa dei Capitelli Colorati in Pompeii Region VII

Friedrich Matz traces this depiction back to a Hellenistic painting from around the middle of the 2nd century BCE although in this painting he points out that Andromeda is turned outwards as an expressionless mantle figure thereby imitating a pyramid group of 4th century BCE Classicism. Paintings of the couple found elsewhere in Pompeii, including in the oecus of Casa dei Capitelli Colorati (VII, 4, 51-31) and the Casa della Saffo, (Pompeii VI) reflect a Roman version wth Perseus looking at Andromeda, not at the mirror image of Medusa.[23]

The south and west walls were originally similarly decorated like the east wall. A third panel painting on the south wall was totally destroyed, probably by earthquake activity as early as 62 CE. Strocka concludes it was probably another heroic pair of lovers representing opposite or complementary aspects of love.

Triclinium Opus Sectile Mosaic

Triclinium Opus Sectile Mosaic Erote Emblem on North Wall of triclinium

Erote Emblem on North Wall of triclinium Adonis and Aphrodite on Triclinium East Wall

Adonis and Aphrodite on Triclinium East Wall Triclinium South Wall detail

Triclinium South Wall detail Triclinium East Wall Main Zone

Triclinium East Wall Main Zone Triclinium South Wall Main Zone

Triclinium South Wall Main Zone Triclinium South Wall Upper Zone

Triclinium South Wall Upper Zone Triclinium North Wall Upper Zone

Triclinium North Wall Upper Zone Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone

Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone

Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone

Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone

Triclinium East Wall Upper Zone

Finds in this largest of the reception rooms included a bronze basin with two handles depicting twisted dolphins with silver ornaments, a bronze basket with two movable handles terminated in swan heads, a bronze vase with a palmette-shaped handle, a large-bellied bronze vase with a swan head and human thumb on the upper handle and vine leaves on the lower end, a bronze vase with two handles of simple work, a bronze lamp with one luminello and double volute handle, four rings containing chains, another ring containing four chains, two bronze studs with rings, four large bronze studs without rings, a long spindle and a circular lead weight with bronze handle.[9]

Apotheca (o)

This corridor-like room, only 34 inches wide by about 6 1/2 feet deep, is thought to have contained a cabinet for herbs or medicinal compounds. It has the same floor pavement as the porticus and appears to have been intentionally created when the exedra (summer triclinium) was constructed within the south side of the porticus. Its walls were painted white with dividing stripes in red and ocher above a black socle. On the east wall is a twisted candelabra overlapped by a red filigree border and fragments of a red ornamental ribbon, green leaf garland with red fruits and a green lion-griffin springing to the left. There is a small window placed in line of sight of the lararium in the garden.[24]

Exedra (summer triclinium) (m)

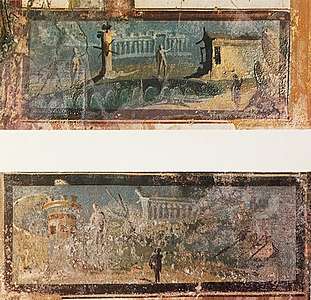

White main and upper zones are painted above a red-violet socle punctuated with floral motifs, dolphins, and, on the south wall a Bucranium, and accented with filigree borders. The south wall main zone features ornate aediculae flanking a framed mural of the god Bacchus clutching his iconic thyrsus staff and pouring wine from a kantharos. His often present panther licks at the wine as it flows down. Bacchus is nude except for a gray cloak draped over his left shoulder. Other scattered animals depicted include swans, goats or antelopes, and griffins with trees and leaf garlands. Three small pinakes are completely faded. A pinax above the framed Bacchus depicts a frontal mask on a green background. Two pinakes to the left and right of Bacchus are citiscapes with human figures and architectural elements.

The west wall has similar depictions of fantastical architecture and animals with a framed mural of the goddess Venus. She is shown wringing the sea water from her hair, a typical pose in Pompeian art. She is completely nude except for gold hoops on her wrists and ankles, two gold necklaces, and two crossed strings held together by a brooch. She also wears a tiara. Above her frame is a pinax but the subject is no longer recognizable.

On the east wall directly across from Venus is a pinax depicting two erotes who have opened a jewelry box. The left erote reaches for a gold hoop in the box while the right erote looks at himself in a hand mirror. A pinax above the central frame is also no longer recognizable.

_House_of_the_Prince_of_Naples_Exedra_erotes_Raddato.jpg) Exedra erotes exploring Venus' jewelry box

Exedra erotes exploring Venus' jewelry box Bacchus closeup

Bacchus closeup Exedra South Wall with Pinax Detail

Exedra South Wall with Pinax Detail Exedra South Wall Detail

Exedra South Wall Detail Exedra East Wall Detail

Exedra East Wall Detail Exedra East Wall Detail

Exedra East Wall Detail Exedra South Wall Pinakes

Exedra South Wall Pinakes

Finds in the exedra include a bronze balsamarium with two handles, a pastry-shaped bronze vessel, a glass lagena with two handles, two bone mirror cases, a spindle and spindle rod, a terracotta grooved pignattino with one handle, another simple terracotta vessel, and a jar in the shape of a drinking glass.[24]As there is thought to have been a three-room apartment above this space, some of the finds could have fallen from the upper floor.[25]

Garden (n)

On the west wall of the garden is a temple-shaped lararium with four stuccoed columns. the capitals are embellished with dark red calathos (flared fruit baskets) with blue acanthus leaves. In the northeast corner of the garden there is still the barrel-shaped clay wellhead of the cistern opening.[26]

Strocka observed that the owners of the house appeared to consciously place the lararium so the lares could "see" into each main room of the house as an apotropaic measure.[27]

During this period, Roman philosophers, including Cicero and Pliny the Elder, were promoting the architectural memory system in which the decoration of the home could serve as a mnemonic trigger. So a view of the lararium may have served to remind the occupants of the home of the importance of pietas and visiting guests of the residents' virtue.[28]

Besides the lararium, finds include a fragmented trapezoid marble table formed by a lion's foot that widens toward the top to support a sculpture of Silenus emerging from acanthus leaves and holding baby Bacchus in his left arm. Excavators also recovered a bronze patera with a fine dog's head handle, a vase with three spouts and a handle supporting a rabbit head, a terracotta amphora, and a bronze handle for a mirror.[26]

Upper floor

None of the upper floor remains after site conservators demolished what was left of it in the early 1970s to facilitate the installation of new ceilings in the ground floor structure to protect visitors. But there were at least two rooms above rooms (a) – (c) which were accessed by a wooden staircase in the northeast corner of the atrium. While the original archaeologist Mau assumed there was a single room above (a) and (b) with a second room above (c), German archaeologists proposed a large room above (b) and (c) with an anteroom above (a). In 1896, before demolition, Mau had observed parts of a south wall and partition wall with connecting door for two further rooms over (e) and (f) accessed via a staircase in the kitchen (g). The staircase in (i) led to a separate private apartment above (i), (k) and (l) and not a terrace. Mau reached this conclusion based on remains of eave gutters. Finds made north of House VI 15, 6 were assumed to be from the upper rooms of the House of the Prince of Naples, most likely from this private apartment.

Finds included two glass jugs, two unguentaria, a bronze hinge, a very small bronze figure of Fortuna with a ring in the back to hang as an amulet, a small bronze surgical instrument with an eye in one end and a ball on the other, two paterae with fine ram's head handles, a horse blinker, a bronze circular mirror, the bottom of a terracotta Arezzo cup with trademark foot, a black varnished luminello with ring handle with depictions of three divinities seated at a table, and a bronze cylindrical inkwell.[25]

Decoration chronology

Although no graffito survives to aid in the dating of the last decoration of the House of the Prince of Naples, German archaeologists point to significant similarities in recurring motifs and compositional elements to the House of the Silver Wedding where graffito in the northern peristyle is dated 6 February 60 CE. This would indicate that structure and probably the House of the Prince of Naples were last redecorated in the second half of the 50s CE. German archaeologists deemed the decoration modest by the standards of the time and suggest it was owned by representatives of the lower middle class. Strocka points out that the marble tables in the atrium and garden provided a little added prestige as needed for guests or family gatherings. He also observed that the sparse repertoire of emblems and simplest form of motifs as well as the conventional, not very refined nature of the paintings in the triclinium and exedra reflect only a simple theme of lovers of life and the epitome of happiness without any intellectual or even philosophical exaggeration.[29]

The inhabitants

With a total floor area of only 260 m2, Strocka estimated the number of the inhabitants at six to ten family members, two to five slaves and journeymen, and an additional family of at least four individuals in the upstairs apartment, for a minimum of 12 to a maximum of about 20 inhabitants. This was based on number of bed niches and their capacity and an estimate based on the size of the upstairs apartment, allotting 14 m2 of living space per head.

Based on its modest size, at less than 1/10 of the size of the sprawling House of the Faun, Pompeii's largest at 2940 m2, Strocka theorized these people must belong to the lower middle class. He also points to the fact that when the house was extended (or rebuilt) during the Augustan-Tiberian period, the goal was not so much to gain more living space but to add a garden, portico and decorative triclinium to provide more air and light in a lower class imitation of the elite's suburban villas. Since the number of bedrooms did not change, he inferred the family had not increased in size. Strocka concludes the probable presence of a workshop or merchant shop in (i) points to the homeowner being a craftsman or small merchant. He observes that a uniquely apotropaic arrangement of window openings to facilitate lines of sight from the garden lararium to each major room, supplemented with a secondary lararium niche in the kitchen to extend supervision of the household gods to cubiciulum (c), the kitchen (g) and the pantry (h), point to a simple-minded, superstitious people. He also concluded their diminished financial status was indicated by roughly repaired earthquake damage, even after 17 years since the major quake of 62 CE.[27]

Other archaeologists' viewpoints

Other archaeologists disagree. Penelope M. Allison, academic archaeologist specializing in the Roman Empire and professor of archaeology at the University of Leicester observes commonly accepted ideas of spatial organization and function in the houses of Pompeii are fraught with unsubstantiated analogical inference as well as cultural and social prejudices derived from nineteen- and early twentieth-century scholarship She emphasizes that particularly the period between 62 and 79 CE cannot be viewed as a static interim phase between two major seismic events with all pre-eruption damage ascribed to the 62 CE earthquake and subsequent repairs made as a result of it.[30]

Her study of 30 atrium-style Pompeian houses, including the House of the Prince of Naples, revealed widespread variations in both structural states of repair and distribution of find assemblages across room types. She observed that ordinary domestic change and ongoing disturbance of some kind (possibly low-level seismic activity) leading up to the final eruption have produced varying patterns of damage, repair, changing room use, and deterioration in Pompeian houses. She said there was a high likelihood the processes of disruption, repair, and abandonment were much less uniform and spread over the final decades in a complex mosaic of disturbance, alteration, and deterioration. Furthermore, processes of post-abandonment intrusion extended for centuries. She observes not only was an earthquake felt in Naples during Nero's reign, in the consulate of Gaius Laecanius and Marcus Licinus (Tacitus Ann. 15, 34) and dated to CE 64,5 but textual evidence also indicates that seismic activity was not unusual in the Campanian region (Seneca Natur. Quaest. 6, 1, 2; Pliny Ep. 6, 20, 3). Pliny the Younger, in his detailed description of the CE 79 eruption, indicated that there had been earthquakes for several days prior to this eruption but that people were not particularly alarmed because such tremors were frequent in the area. Pliny the Elder's belief (Nat. Hist. 2, 198) that earthquakes could continue for up to two years may well have been founded on phenomena observed from his base at Misenum near Naples. Thus, assumptions that a final phase of Pompeii can be identified through damage and repair to its buildings and can be dated from CE 62 represent a misreading of the written documentation.[31]

In her analysis of amphorae finds, she comments on amphorae containing building repair material discovered in the Casa del Menandro, the Casa di Julius Polybius, the Casa dei Quadretti Teatrali and the Casa dell'Efebo. This indicates repairs were in progress in houses much larger and probably wealthier than the Casa del Principe di Napoli at the time of eruption.[32]

Strocka points to the arrangement of the lararium in the garden and its line of sight through various strategically placed apertures as an indication the inhabitants were more religiously observant than average households or those of the educated elite. But Allison's study found fixtures associated with religious activities like aediculae in 17 of the 30 houses, including the far larger Casa del Menandro and such fixtures were found in five rooms there. Strocka's discussion of religious indications also include the niche found in the kitchen. But Allison points out that, although niches decorated with Lares-related scenes or containing small ritual sculptures have been found in a number of kitchens elsewhere in Pompeii, usually in structures without aediculae, the undecorated niches in the Casa del Principe di Napoli, as well as in other structures around Pompeii, could have served some other purpose.[33]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Casa del Principe di Napoli. |

Notes

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (1994). Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02909-2.

- Strocka 1984, p. 17.

- Dobbins, John J.; Foss, Pedar W. (2007). The World of Pompeii. New York NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47577-8.

- Strocka 1984, p.18

- Strocka 1984, p.19.

- Strocka 1984, p. 19.

- Strocka 1984, pp. 19-24.

- Clarke, John R. (1991). The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. London, England: University of California Press Ltd. ISBN 0-520-08429-2.

- Strocka 1984, p.26.

- Strocka 1984, pp. 24 – 29.

- Strocka 1984, p. 50.

- Strocka 1984, p.29.

- Strocka 1984, p. 18.

- Strocka 1984, p. 20.

- Strocka 1984, p. 21.

- Strocka 1984, page 22.

- Strocka 1984, p. 22.

- Strocka 1984, p. 23.

- Strocka 1984, p. 24.

- Strocka 1984, p. 25.

- Strocka 1984, p. 26.

- Strocka 1984, p.43

- Strocka 1984, p. 44.

- Strocka 1984, p. 29.

- Strocka 1984, p. 33.

- Strocka 1984, p. 32.

- Strocka 1984, p. 49.

- Bergmann, B. (1994). The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii. The Art Bulletin, 76(2), 225-256. doi:10.2307/3046021

- Strocka 1984, p. 35.

- Allison 2004, p. 8.

- Allison 2004 pp. 15-18.

- Allison 2004, pp. 150-152.

- Allison 2004, pp. 50-51.

References

- Strocka, Volker Michael (1984). Hauser in Pompeji (Volume 1): Casa del Principe di Napoli. Berlin, Germany: German Archaeological Institute. ISBN 978-3803010322.

- Allison, Penelope M. (2004). Pompeian Households: An Analysis of Material Culture (Monograph Book 42). Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. ISBN 9781938770944.