History of Oradea

The history of Oradea covers the time from Neolithic, through the Middle Ages and its flourishing as an important center in Crișana region, until its modern existence as a city, the seat of Bihor County in north-western Romania.

Prehistory and ancient times

While modern Oradea is first mentioned later, recent archaeological findings, in and around the city, provide evidence of a more or less continuous habitation since the Neolithic.[1] The Dacians and Celts also inhabited the region. After the conquest of Dacia, the Romans established a presence in the area, most notably in the Salca district of the city and modern day Băile Felix.[2][3]

Middle Ages

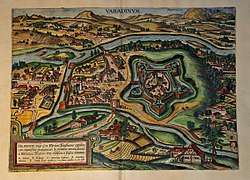

According to the Gesta Hungarorum the territory was ruled by a legendary ruler Menumorut – having its citadel centered at Bihar – at the end of the 9th and beginning of the 10th centuries, until the Hungarian land-taking.[4] The first documented mention of Oradea's name was in 1113 under the Latin name, Varadinum ("vár" means fortress in Hungarian). In the 11th century when St. King Ladislaus I of Hungary founded a bishopric settlement near the city of Oradea, the present Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea. The city flourished during the 13th century in particular. The Citadel of Oradea, the ruins of which remain today, was first mentioned in 1241 during the Mongol invasion of Europe. The 14th century was one of the most prosperous periods in the city's life. Statues of St. Stephen, Emeric and Ladislaus (before 1372) and the equestrian sculpture of St. Ladislaus (1390) were erected in Oradea. St. Ladislaus' statue was the first proto-renaissance public square equestrian in Europe. Bishop Andreas Báthori (1329–1345) rebuilt the cathedral in Gothic style. From that epoch dates also the Hermes, now preserved at Györ, which contains the skull of King Ladislaus, and which is a masterpiece of the Hungarian goldsmith's art.[5]

Early modern

Georg von Peuerbach worked at the Observatory of Varadinum, using it as the reference of prime meridian of the Earth in his Tabula Varadiensis, published posthumously in 1464. Oradea was used for maps and navigation as the prime meridian between 1464 and 1667.[6] In 1474, the city was attacked by the Turks. It was not until the 16th century that Oradea began growing as an urban area. The Peace of Várad was concluded between Ferdinand I and John Zápolya on February 4, 1538, in which they mutually recognized each other to be king. In the 18th century, the Viennese engineer Franz Anton Hillebrandt planned the city in the Baroque style. Beginning in 1752, many landmarks were constructed such as the Roman Catholic Cathedral and the Bishop's Palace, presently the Muzeul Țării Crișurilor ("The Museum of the Criș-es land").

After the Ottoman invasion of Hungary in the 16th century, the city was administered at various times by the Principality of Transylvania, the Ottoman Empire, and the Habsburg Monarchy. In 1598, the fortress was besieged and, on August 27, 1660, Oradea fell to the Turks and became the capital of the Varat Province. This eyalet included Varat (Oradea), Salanta, Debreçin (formerly part of Budin and Eğri Eyalets), Halmaș, Sengevi and Yapıșmaz sanjaks. The siege is described in detail by Szalárdy János in his contemporary chronicle. The city was seized by the Habsburg-led German-Hungarian-Croatian forces in September 1692.

Late modern

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 played an important role in the city's history. It was the home of the largest Hungarian arms factory while Debrecen was the temporary seat of the Hungarian government.[7] In the second half of the 19th century, literary nicknames for the town included "Hungarian Compostela", "Felix civitas", "Paris on the River Pece", "the City of Tomorrow", "Athens on the Körös", and "the City of Yesterday". These nicknames are not widely used today, although "Paris on the River Pece" is still utilized sometimes.

Twentieth century

As a consequence of Hungary's role in World War I, the Treaty of Trianon awarded Oradea to the Kingdom of Romania. Over 90% of the city's population was Hungarian then. Under the Second Vienna Award brokered by Germany and Italy in 1940, North Transylvania was returned to Hungary, including Oradea, but, being on the losing side again, had to relinquish claims to it under the Treaty of Paris which concluded on February 10, 1947.

In 1925, the status of municipality was given to Oradea, dissolving its former civic autonomy. Under the same ordinance, its name was changed from Oradea Mare ("Great" Oradea) to simply Oradea.

In the past, ethnic tensions sometimes ran high in the area, but the different ethnic groups now live together in harmony in general, thriving on each other's contributions to modern culture. There are many mixed Romanian-Hungarian families in Oradea, with children assimilating into both of their parents' cultures and learning to speak both languages.

After the Romanian revolution

After December 1989, Oradea aimed to achieve greater prosperity along with other towns in Central Europe. Both culturally and economically, Oradea's prospects are inevitably tied to the general aspiration of the Romanian society to freedom, democracy and a free market economy, with varied initiatives in all fields of endeavor. Due to its specific character, Oradea is one of the most important economic and cultural centers of Western Romania and of the country in general, and one of the great academic centers, with a unique bilingual dynamic.[8]

Jewish community

The chevra kadisha was founded in 1735, the first synagogue in 1803, and the first communal school in 1839. Until the beginning of the 19th century, Jews were not permitted to do business in any other part of the city. Even then they were required to withdraw at nightfall to their own quarter. In 1835, permission to live at will in any part of the city was granted to them.

The Jewish community of Oradea was divided into an Orthodox and Neolog congregations. While the members of the Neolog community still retained their membership in the chevra kadisha, they began to use a cemetery of their own in 1899. By the early 20th century, the Jews of Oradea had won prominence in the public life of the city; there were Jewish manufacturers, merchants, lawyers, physicians, and farmers. The chief of police (1902) was a Jew and in the municipal council, and the Jewish element was proportionately represented. The community possessed, in addition to the hospital and chevra kadisha, a Jewish women's association, a grammar school, an industrial school for boys and girls, a yeshiva, and a soup kitchen to name a few.

The following are among those who have held the rabbinate of Oradea:

- Naftali Hirtz Lifchovitz (Orthodox);

- Joseph Rosenfeld (Orthodox);

- David Joseph Wahrmann (Orthodox);

- Aaron Landesberg (Orthodox);

- Moricz Fuchs (Orthodox);

- Alexander Rosenberg (Neolog: removed to Arad);

- Alexander Kohut (Neolog: removed to New York, 1885; died, 1894);

- Leopold Kecskeméty (Neolog).

According to the Center for Jewish Art:

The Oradea Jewish community was once the most active communities, both commercially and culturally, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1944, 25,000 Oradean Jews were deported to concentration camps, thus decimating this vital community. Three hundred Jews reside in Oradea today. In the center of the city, towering over other buildings in the area, is the large Neolog Temple Synagogue built in 1878. The unusual cube-shaped synagogue with its large cupola is one of the largest in Romania. The inside has a large organ and stucco decorations. In 1891, the Orthodox community also built a complex of buildings, including two synagogues and a community center.[9]

See also

Notes

- "Descoperire importantă la Oradea" (in Romanian). Pro TV. October 11, 2017.

- Cataldi Raffaele; Hodgson Susan; Lund John (1999). Stories from a Heated Earth, Our Geothermal Heritage. Geothermal Resources Council. p. 245. ISBN 0934412197.

- E. J. Brill. Rumanian Studies, Vol. 3. Brill Publishers, Leiden, 1976.

- Oradea on Britannica

- "Roman Catholic Basilica in Oradea, | Expedia". www.expedia.com. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- "Romanian astronaut marks 10th anniversary of Prime Meridian Astronomy Club | Nine O`Clock". www.nineoclock.ro. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- "Ethnic features of symbolic appropriation of public space in changing geopolitical frames – the case of Oradea/Nagyvárad". www.academia.edu. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- www.danmilas.eu, Dan Milas -. "Oradea, Bihor - AGORA - Youth Project". www.agoratineret.ro. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- "Uncovering and Documenting Jewish Art and Architecture in Western Romania". Center for Jewish Art. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Summer 1998. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

References

- By : Gotthard Deutsch & G. Kecskeméti (JewishEncyclopedia.com – GROSSWARDEIN (NAGY-VARAD))

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Oradea. |