Georg von Peuerbach

Georg von Peuerbach (also Purbach, Peurbach, Purbachius; born May 30, 1423 – April 8, 1461[2]) was an Austrian astronomer, mathematician and instrument maker, best known for his streamlined presentation of Ptolemaic astronomy in the Theoricae Novae Planetarum.

Georg von Peuerbach | |

|---|---|

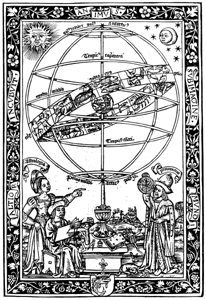

Georg von Peuerbach: Theoricarum novarum planetarum testus, Paris 1515 | |

| Born | May 30, 1423 |

| Died | April 8, 1461 (aged 37) |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | University of Vienna |

| Academic advisors | Johannes von Gmunden[1] |

| Notable students | Regiomontanus[1] |

Biography

Little is known of Peuerbach's life before he enrolled at the University of Vienna in 1446.[3] He received his Bachelor of Arts in 1448. His curriculum was most likely composed primarily of humanities courses, as was usual at the time.[4] His knowledge of astronomy probably derived from independent study, as there were no professors of astronomy at the University of Vienna during Peuerbach's enrollment.[4]

From 1448 to 1451 Peuerbach traveled through central and southern Europe, most notably in Italy, giving lectures on astronomy. His lectures led to offers of professorships at several universities, including those at Bologna and Padua. During this time he also met Italian astronomer Giovanni Bianchini of Ferrara.[4] He returned to the University of Vienna in 1453, earned his Masters of Arts, and began lecturing on Latin poetry.[3]

In 1454 Peuerbach was appointed court astrologer to King Ladislas V of Bohemia and Hungary. It was in this capacity that Peuerbach first met Ladislas' cousin Frederick who was then serving as guardian to the 14-year-old king and who would later become Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. Ladislas resided primarily in Prague and Vienna, allowing Peuerbach to maintain his position at the University of Vienna. During this time Peuerbach met Johannes Müller von Königsberg, better known as Regiomontanus. Müller was currently a student at the university and, after he graduated in 1452 at the age of 15, began collaborating extensively with Peuerbach in his astronomical work.[4]

In 1457, following the assassination of two notable political figures, Ladislas fled Vienna and died later that year. Rather than taking of service with either of Ladislas' successors, Peuerbach accepted an appointment as court astrologer to Frederick III.[4]

Works

One of Peuerbach's best known works is his Theoricae Novae Planetarum. It began as a series of lectures transcribed by Regiomontanus. The Theoricae Novae was an attempt to present Ptolemaic astronomy in a more elementary and comprehensible way. The book was very successful, replacing the older Theorica Planetarum Communis, sometimes attributed to a certain Gerardus Cremonensis, as the standard university text on astronomy and was studied by many later-influential astronomers including Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler.[3]

In 1457 Peuerbach observed an eclipse and noted that it had occurred 8 minutes earlier than had been predicted by the Alphonsine Tables, the best available eclipse tables at the time. He then computed his own set of eclipse tables, the Tabulae Eclipsium. Widely read in manuscript form beginning around 1459 and formally published in 1514, these tables remained highly influential for many years.[3][4]

Peuerbach wrote various papers on practical mathematics, and constructed various astronomical instruments. Most notably, he computed sine tables based on techniques developed by Arabian mathematicians.[3]

In 1460, Cardinal Johannes Bessarion, while visiting Frederick's court seeking assistance in a crusade to reclaim Constantinople from the Turks, proposed that Peuerbach and Regiomontanus create a new translation of Ptolemy's Almagest from the original Greek. Bessarion thought that a shorter and more clearly written version of the work would make a suitable teaching text. Peuerbach accepted the task and worked on it with Regiomontanus until his death in 1461, at which time 6 volumes had been completed. Regiomontanus completed the project, the final version containing 13 volumes.[4]

Notes

- The Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Hermann Haupt (2001), "Peu(e)rbach (auch Purbach), Georg von (eigentlich Georg Aunpekh)", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 20, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 281–282; (full text online)

- Shank, Michael. "Georg von Peuerbach". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- J. J. O'Connor; E. F. Robertson. "Georg Peuerbach". Retrieved 2014-03-09.

References

- Attribution

Further reading

- Ralf Kern: Wissenschaftliche Instrumente in ihrer Zeit. Band 1: Vom Astrolab zum mathematischen Besteck. Köln, 2010.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Georg von Peuerbach", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Electronic facsimile-editions of the rare book collection at the Vienna Institute of Astronomy

External links

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Georg von Peuerbach at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Thony C (May 30, 2011). "The astronomical revolution didn't start here!". The Renaissance Mathematicus. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Georg von Peurbach in .jpg and .tiff format.