History of Cape Town

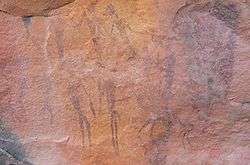

The area known today as Cape Town has no written history before it was first mentioned by Portuguese explorer Bartholomeu Dias in 1488. The German anthropologist Theophilus Hahn recorded that the original name of the area was '||Hui !Gais' – a toponym in the indigenous Khoe language meaning "where clouds gather."[7]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of South Africa |

Arms of South Africa |

|

|

Topic

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1658 | 360 | — |

| 1731 | 3,157 | +3.02% |

| 1836 | 20,000 | +1.77% |

| 1875 | 45,000 | +2.10% |

| 1891 | 67,000 | +2.52% |

| 1901 | 171,000 | +9.82% |

| 1950 | 618,000 | +2.66% |

| 1955 | 705,000 | +2.67% |

| 1960 | 803,000 | +2.64% |

| 1965 | 945,000 | +3.31% |

| 1970 | 1,114,000 | +3.35% |

| 1975 | 1,339,000 | +3.75% |

| 1980 | 1,609,000 | +3.74% |

| 1985 | 1,933,000 | +3.74% |

| 1990 | 2,296,000 | +3.50% |

| 1996 | 2,565,018 | +1.86% |

| 2001 | 2,892,243 | +2.43% |

| 2007 | 3,497,097 | +3.22% |

| 2011 | 3,740,025 | +1.69% |

| 2016 | 4,005,016 | +1.38% |

| Note: Census figures (1996–2011) cover figures after 1994 reflect the greater Cape Town metropolitan municipality reflecting post-1994 reforms. Sources: 1658-1904,[1] 1950-1990,[2]

1996,[3] 2001, and 2011 Census;[4] 2007,[5] 2016 Census estimates.[6] | ||

The arrival of Europeans

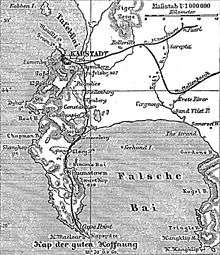

The first Europeans to discover the Cape were the Portuguese. Bartholomeu Dias arrived in 1488 after journeying south along the west coast of Africa. The next recorded European sighting of the Cape was by Vasco da Gama in 1497 while he was searching for a route that would lead directly from Europe to Asia.

Table Mountain was given its name in 1503 by António de Saldanha, a Portuguese admiral and explorer.[8] He called it Taboa da caba ("table of the cape"). The name given to the mountain by the Khoi inhabitants was Hoeri 'kwaggo ("sea mountain").[9].

1652: Arrival of the Dutch

The area fell out of regular contact with Europeans until 1652, when Jan van Riebeeck and other employees of the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or simply VOC) were sent to the Cape to establish a halfway station to provide fresh water, vegetables, and meat for passing ships travelling to and from Asia. Van Riebeeck's party of three vessels landed at the cape on 6 April 1652. The Cape was under Dutch rule from 1652 to 1795 and again from 1803 to 1806.[10] The group quickly erected shelters and laid out vegetable gardens and orchards, and are preserved in the Company’s Garden. Water from the Fresh River, which descended from Table Mountain, was channelled into canals to provide irrigation. The settlers bartered with the native Khoisan for their sheep and cattle. Forests in Hout Bay and the southern and eastern flanks of Table Mountain provided timber for ships and houses. At this point, the VOC had a monopoly on trade and prohibited any private trade. The Dutch gave their own names to the native inhabitants that they encountered, calling the pastoralists "Hottentots", those that lived on the coast and subsisted on shellfishing "Strandlopers", and those who were hunter-gatherers were named "Bushmen".

The first wave of Asian immigration to South Africa started in 1654. These first immigrants were banished to the Cape by the Dutch Batavian High Court. These Asians helped to form the foundation of the Cape Coloured and Cape Malay populations, as well as bringing Islam to the Cape. The first large territorial expansion occurred in 1657, when farms were granted by the VOC to a few servants in an attempt to increase food production. These farms were situated along the Liesbeeck River and the VOC still retained financial control of them. The first slaves were brought to the Cape from Java and Madagascar in the following year to work on the farms.[11] The first of a long series of border conflicts between the inhabitants in the European-controlled area and native inhabitants began in 1658 when settlers clashed with the Khoi, who realised that they were losing territory.

Work on the Castle of Good Hope, the first permanent European fortification in the area, began in 1666. The new castle replaced the previous wooden fort that Van Riebeeck and his men built. Finally completed in 1679, the castle is the oldest building in South Africa.

Simon van der Stel, after whom the town of Stellenbosch is named, arrived in 1679 to replace Van Riebeeck as governor. Van der Stel founded the Cape wine industry by bringing grape vines with him on his ship, an industry which would quickly grow to be important for the region. He also promoted territorial expansion in the Colony.

The first non-Dutch immigrants to the Cape, the Huguenots, arrived in 1688. The Huguenots had fled from anti-Protestant persecution in Catholic France to the Netherlands, where the VOC offered them free passage to the Cape as well as farmland. The Huguenots brought important experience in wine production to the Cape, greatly bolstering the industry, as well as providing strong cultural roots.

The 1700s

By 1754, the population of the settlement on the Cape had reached 5,510 Europeans and 6,729 slaves. But by 1780, France and Great Britain went to war against each other. The Netherlands entered the war on the French side, and thus a small garrison of French troops were sent to the Cape to protect it against the British. These troops, however, left by 1784. By 1795, however, the Netherlands was invaded by France and the VOC was in complete financial ruin. The Prince of Orange fled to England for protection, which allowed for the establishment of the Dutch Batavian Republic. Due to the long time it took to send and receive news from Europe, the Cape Commissioner of the time knew only that the French had been taking territory in the Netherlands and that the Dutch could change sides in the war at any moment. British forces arrived at the Cape bearing a letter from the Prince of Orange asking the Commissioner to allow the British troops to protect the Cape from France until the war. The British informed the Commissioner that the Prince had fled to England. The reaction in the Cape Council was mixed, and eventually the British successfully invaded the Cape in the Battle of Muizenberg. The British immediately announced the beginning of free trade.

As elsewhere in Africa and other parts of the world, trading in slaves was a significant activity. A notable event was the mutiny, in 1766, of the slaves on the slaver ship Meermin.[12][13]

The 1800 and 1900s

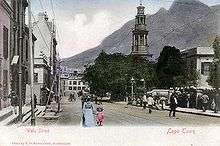

Under the terms of a peace agreement between Britain and France, the Cape was returned to the Dutch in 1802. Three years later, however, the war resumed and the British returned their garrison to the Cape after defeating Dutch forces at the Battle of Blaauwberg (1806).[14] This period saw major developments for the city, and can be said to be the start of Cape Town as a city in its own right. Taps and iron pipes were installed along major streets in the city. The native inhabitants were forced to declare a fixed residence and were not permitted to move between regions without written permission. The war between France and England ended in 1814 with a British victory. The British drew up a complex treaty whereby pieces of real estate were exchanged for money by various countries. The Cape was permanently taken from the Dutch by the British in return for a large sum of money. In this period, the British saw the control of the Cape as key to their ability to maintain their command in India. The Dutch government was too impoverished and depleted to argue, and agreed with the condition that they be allowed to continue to use the Cape for repairs and refreshment.

The vagrancy and pass laws of 1809 were repealed in 1829. Thus, the Khoikhoi, in theory, were equal with the Europeans. As in the rest of the British Empire, slaves – estimated to be around 39,000 in number – were emancipated in 1834. This led to the establishment of the Bo-Kaap by a Muslim community after being freed. The Cape Town Legislative Council was also established in the same year. One of the most momentous events in South African history, the Great Trek (Afrikaans: die Groot Trek), began in 1836. About 10,000 Dutch families, for various reasons, left for the north in search of new land, thereby opening up the interior of the country. Further political development occurred in 1840 when the Cape Town Municipality was formed. At its inception, the population stood at 20,016, of which 10,560 were white.

Ensuing political developments now saw gradual moves towards greater independence from Britain and towards a degree of political inclusiveness. In 1854, the Cape Colony elected its first parliament, on the basis of the multiracial Cape Qualified Franchise, whereby suffrage qualifications applied universally, regardless of race. After a long political struggle, this was followed by responsible government in 1872, when the Cape won the right to elect its own locally-accountable executive and Prime Minister. A period of strong economic growth and social development ensued, with a rapid expansion of the Cape Government Railways and other infrastructure, connecting Cape Town to the Cape's vast interior.[15]

The discovery and subsequent exploitation of diamonds and gold in the former Transvaal region in the central highveld in the 1870s and 1880s led to rapid change in Cape Town, as well as in Cape Colony as a whole. In particular, the rise to power of the ambitious colonialist Cecil Rhodes, fueled by the new diamond industry, led to great instability. On becoming the Cape's new Prime Minister, he restricted the multiracial Cape franchise, and instigated a rapid expansion of British influence into the hinterland. A rise in inter-ethnic tensions ensued, followed by the Anglo-Boer War.[16]

As the city of Johannesburg grew from the gold fields, Cape Town lost its position as the single dominant city in the region, but, as the primary port, it nonetheless benefitted from the increased trade to the region. The mineral wealth generated in this period laid the foundation for an industrialised society. This period marked the first incident of segregation in the city. Following an outbreak of bubonic plague which was blamed on the native Africans, the natives were moved to two locations outside of the city, one of which was near the docks and the other at Ndabeni, about six km east of the city.

The apartheid years

The latter settlement was the start of what would later develop into the townships of the Cape Flats. In 1948, the National Party stood for election on its policy of racial segregation, later known as apartheid. After a series of bitter court and constitutional battles, the already limited voting rights of the Coloured community in Cape Province were revoked. In 1966, the once-vibrant District Six area was bulldozed and declared a white-only area.[17] This and many similar declarations under the Group Areas Act resulted in whole communities being uprooted and relocated to the Cape Flats.

Under apartheid, the Cape was considered a "Coloured labour preference area", to the exclusion of Black Africans. The government tried for decades to remove largely Xhosa squatter camps, such as Crossroads, which were the focal point for black resistance in the Cape area to the policies of apartheid. In the last forced removal, between May and June 1986, an estimated 70,000 people were expelled from their homes.

Recent times

Hours after being released from prison on 11 February 1990, Nelson Mandela made his first public speech in decades from the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall, heralding the beginning of a new era for South Africa.

In late August 1998, a terrorist explosion rocked the city's packed Planet Hollywood restaurant, killing one and injuring dozens.[18]

Water Crisis

Beginning in 2015, Cape Town entered a drought that lasted into 2018. The city was projected to run out of water, but a combination of rainfall and savings by residents averted this scenario.[19]

See also

- Timeline of Cape Town history

- Greenmarket Square

- Autshumato

- Krotoa

- Trams in Cape Town

- Trolleybuses in Cape Town

References

- Worden, Nigel; van Hyningen, Elizabeth; Bickford-Smith, Vivian (1998). Cape Town: The Making of a City. Claremont, Cape Town, South Africa: David Philip Publishers. p. 212. ISBN 0-86486-435-3.

- "Population estimates for Cape Town, South Africa, 1950-2015". Mongabay.com. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Census 96 : Community Profile". City of Cape Town. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "City of Cape Town – 2011 Census – Cape Town" (PDF). City of Cape Town. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Small, Karen (December 2008). "Demographic and Socio-economic Trends for Cape Town: 1996 to 2007" (PDF). City of Cape Town. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Provincial profile: Western Cape Community Survey 2016" (PDF).

- Hahn, T. Tsuni-IIGoam: The Supreme Being of the Khoi-Khoi, Trübner's Oriental Series, 1881

- http://www.cape-town.info/cape-town-information/history-of-cape-town/

- "South African National Parks - SANParks - Official Website - Accommodation, Activities, Prices, Reservations". www.sanparks.org. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- J. A. Heese, Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner 1657 - 1867. A. A. Balkema, Kaapstad, 1971. CD Colin Pretorius 2013. ISBN 978-1-920429-13-3. Bladsy 15.

- "Slavery and early colonisation in South Africa". South African History Online. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- "Slave Ship Mutiny". PBS. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "The Slave Mutiny on the slaver ship Meermin". Cape Slavery Heritage. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Morris, Michael; John Linnegar (2004). Every Step of the Way: The Journey to Freedom in South Africa. Ministry of Education. pp. 58–95. ISBN 0-7969-2061-3.

- McCracken, J.L. "The Cape Parliament, 1854-1910". Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1967. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Mbenga, Bernard. "New History of South Africa". Tafelberg, South Africa, 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- "Recalling District Six". SouthAfrica.info. 19 August 2003.

- "FBI joins Planet Hollywood inquiry". BBC News. 26 August 1998. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-06-28-day-zero-is-called-off-for-now-but-restrictions-retained/

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Cape Town. |