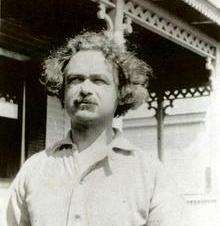

Hippolyte Havel

Hippolyte Havel (1871–1950) was a Czech-American anarchist who was known as an activist in the United States and part of the radical circle around Emma Goldman in the early 20th century. He had been imprisoned as a young man in Austria-Hungary because of his political activities, but made his way to London. There he met anarchist Emma Goldman on a lecture tour from the United States. She befriended him and he immigrated to the US.

He settled in Greenwich Village, New York, a center of radicals, artists and writers. He declared the neighborhood to be "a spiritual zone of mind".[1][2] For a time he and his wife ran a restaurant in the village. He also edited radical journals. He was close friends with Emma Goldman, and also became friends with playwright Eugene O'Neill, and various others in the artistic circles.

History

Born and raised in what is now the Czech Republic and was then part of Austria-Hungary, Havel became involved in the anarchist movement as a young man. In his youth, he was imprisoned by empire authorities in Austria-Hungary for anarchist activities. At the time, he was declared as "criminally insane", but he was declared sane by the intervention of Richard von Krafft-Ebing, a noted Austro-German psychiatrist. As a result, Havel was transferred from the prison madhouse to an ordinary prison and the general population.[3]

He managed to flee to London. There in November 1899, he met the American anarchist and activist Emma Goldman, who was on a lecture tour. They traveled together to Paris, France, where he helped her with preparations for the September 1900 International Anti-Parliamentary Congress.

Havel traveled with Goldman from Europe to the United States, entering as an immigrant, and settled in Chicago. For a time he shared a residence with her, and Mary and Abe Isaak, an anarchist couple, and their family.[4][5] In September 1901 Goldman, Havel, Isaak, and ten other anarchists were arrested as suspects in connection with Leon Czolgosz's assassination of President William McKinley.[6] Czolgosz had said he was inspired by a speech of Goldman's. Although he insisted she had no direct involvement in his action, Goldman was held by police for two weeks. Havel and the other anarchists were released earlier. The assassination generated considerable anti-anarchist reaction politically, and most anarchists disavowed Czolgosz's actions.

Havel worked for a time in Chicago as the editor of several anarchist publications, including the Chicago Arbeiter Zeitung, published in German.[3] He later worked as editor on The Revolutionary Almanac (1914), and Revolt (1916). Sometime in the early 1900s, both he and Goldman moved to New York, where they lived in Greenwich Village, a center of radical politics, and artists and writers.

There Havel married Polly Holliday, an anarchist who with him ran a restaurant on Washington Square in Greenwich Village. It was frequented by radicals, artists and writers.[3] Havel may also have been Goldman's lover even after his marriage to Polly.[7] In the late 1910s, Havel took in Berenice Abbott as his adopted daughter. She became a noted photographer.

Havel wrote a biography of Emma Goldman and an introductory essay to her collected Anarchism and Other Essays (1910). He also contributed dozens of articles and essays to anarchist journals, including Goldman's Mother Earth. His essay, "What Is Anarchism?" was published also in 1932. A collection of his writings was published for the first time in 2018.

Havel became friends in this period with playwright Eugene O'Neill. The writer based the character Hugo Kalmar in The Iceman Cometh on Havel.[8]

The Yale Hippolytic (or The Hippolytic), a left-wing student publication at Yale University, is named after Havel, to honor his life of cosmopolitan dissent.

Works

- "Harry Kelly: An Appreciation" (1921)

- "What is Anarchism?" (1932)

- Proletarian Days: A Hippolyte Havel Reader, edited by Nathan Jun; Barry Pateman (Introduction); AK Press (2018, paperback) ISBN 978-1849353281

See also

- Anarchism in the United States

- Czech American

References

- Havel, Hippolyte (14 Aug 1915), "The Spirit of the Village", Bruno's Weekly: 34–35

- McFarland, Gerald W. (2005), Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918, Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press, p. 207, ISBN 978-1-55849-502-9

- Alexander, Doris (1962). The Tempering of Eugene O'Neill. Harcourt Brace & World.

- Drinnon, Richard and Anna Maria, eds. Nowhere At Home: Letters from Exile of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. New York: Schocken Books, 1975, p. 68. OCLC 1055309

- Chalberg, John. Emma Goldman: American Individualist. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 1991, p. 73. ISBN 0-673-52102-8

- Wexler, Alice. Emma Goldman: An Intimate Life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984. ISBN 0-394-52975-8. Republished as Emma Goldman in America. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984, p. 104. ISBN 0-8070-7003-3

- Chalberg (1991) Goldman: Individualist, p. 67.

- Alexander, Doris (2005). Eugene O'Neill's Last Plays: Separating Art from Autobiography. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2709-3.

External links

- Works by Hippolyte Havel at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hippolyte Havel at Internet Archive

- Proletarian Days: A Hippolyte Havel Reader, ed. Nathan Jun, AK Press, Kindle Edition (2018)

- Photo of Hippolyte Havel, from Eugene O'Neill website