Hill climbing

In numerical analysis, hill climbing is a mathematical optimization technique which belongs to the family of local search. It is an iterative algorithm that starts with an arbitrary solution to a problem, then attempts to find a better solution by making an incremental change to the solution. If the change produces a better solution, another incremental change is made to the new solution, and so on until no further improvements can be found.

| Graph and tree search algorithms |

|---|

| Listings |

|

| Related topics |

For example, hill climbing can be applied to the travelling salesman problem. It is easy to find an initial solution that visits all the cities but will likely be very poor compared to the optimal solution. The algorithm starts with such a solution and makes small improvements to it, such as switching the order in which two cities are visited. Eventually, a much shorter route is likely to be obtained.

Hill climbing finds optimal solutions for convex problems – for other problems it will find only local optima (solutions that cannot be improved upon by any neighboring configurations), which are not necessarily the best possible solution (the global optimum) out of all possible solutions (the search space). Examples of algorithms that solve convex problems by hill-climbing include the simplex algorithm for linear programming and binary search.[1]:253 To attempt to avoid getting stuck in local optima, one could use restarts (i.e. repeated local search), or more complex schemes based on iterations (like iterated local search), or on memory (like reactive search optimization and tabu search), or on memory-less stochastic modifications (like simulated annealing).

The relative simplicity of the algorithm makes it a popular first choice amongst optimizing algorithms. It is used widely in artificial intelligence, for reaching a goal state from a starting node. Different choices for next nodes and starting nodes are used in related algorithms. Although more advanced algorithms such as simulated annealing or tabu search may give better results, in some situations hill climbing works just as well. Hill climbing can often produce a better result than other algorithms when the amount of time available to perform a search is limited, such as with real-time systems, so long as a small number of increments typically converges on a good solution (the optimal solution or a close approximation). At the other extreme, bubble sort can be viewed as a hill climbing algorithm (every adjacent element exchange decreases the number of disordered element pairs), yet this approach is far from efficient for even modest N, as the number of exchanges required grows quadratically.

Hill climbing is an anytime algorithm: it can return a valid solution even if it's interrupted at any time before it ends.

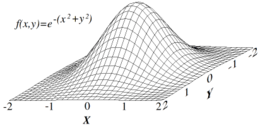

Mathematical description

Hill climbing attempts to maximize (or minimize) a target function , where is a vector of continuous and/or discrete values. At each iteration, hill climbing will adjust a single element in and determine whether the change improves the value of . (Note that this differs from gradient descent methods, which adjust all of the values in at each iteration according to the gradient of the hill.) With hill climbing, any change that improves is accepted, and the process continues until no change can be found to improve the value of . Then is said to be "locally optimal".

In discrete vector spaces, each possible value for may be visualized as a vertex in a graph. Hill climbing will follow the graph from vertex to vertex, always locally increasing (or decreasing) the value of , until a local maximum (or local minimum) is reached.

Variants

In simple hill climbing, the first closer node is chosen, whereas in steepest ascent hill climbing all successors are compared and the closest to the solution is chosen. Both forms fail if there is no closer node, which may happen if there are local maxima in the search space which are not solutions. Steepest ascent hill climbing is similar to best-first search, which tries all possible extensions of the current path instead of only one.

Stochastic hill climbing does not examine all neighbors before deciding how to move. Rather, it selects a neighbor at random, and decides (based on the amount of improvement in that neighbor) whether to move to that neighbor or to examine another.

Coordinate descent does a line search along one coordinate direction at the current point in each iteration. Some versions of coordinate descent randomly pick a different coordinate direction each iteration.

Random-restart hill climbing is a meta-algorithm built on top of the hill climbing algorithm. It is also known as Shotgun hill climbing. It iteratively does hill-climbing, each time with a random initial condition . The best is kept: if a new run of hill climbing produces a better than the stored state, it replaces the stored state.

Random-restart hill climbing is a surprisingly effective algorithm in many cases. It turns out that it is often better to spend CPU time exploring the space, than carefully optimizing from an initial condition.

Problems

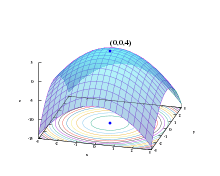

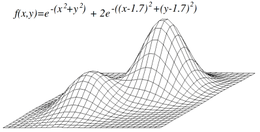

Local maxima

Hill climbing will not necessarily find the global maximum, but may instead converge on a local maximum. This problem does not occur if the heuristic is convex. However, as many functions are not convex hill climbing may often fail to reach a global maximum. Other local search algorithms try to overcome this problem such as stochastic hill climbing, random walks and simulated annealing.

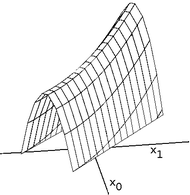

Ridges and alleys

Ridges are a challenging problem for hill climbers that optimize in continuous spaces. Because hill climbers only adjust one element in the vector at a time, each step will move in an axis-aligned direction. If the target function creates a narrow ridge that ascends in a non-axis-aligned direction (or if the goal is to minimize, a narrow alley that descends in a non-axis-aligned direction), then the hill climber can only ascend the ridge (or descend the alley) by zig-zagging. If the sides of the ridge (or alley) are very steep, then the hill climber may be forced to take very tiny steps as it zig-zags toward a better position. Thus, it may take an unreasonable length of time for it to ascend the ridge (or descend the alley).

By contrast, gradient descent methods can move in any direction that the ridge or alley may ascend or descend. Hence, gradient descent or the conjugate gradient method is generally preferred over hill climbing when the target function is differentiable. Hill climbers, however, have the advantage of not requiring the target function to be differentiable, so hill climbers may be preferred when the target function is complex.

Plateau

Another problem that sometimes occurs with hill climbing is that of a plateau. A plateau is encountered when the search space is flat, or sufficiently flat that the value returned by the target function is indistinguishable from the value returned for nearby regions due to the precision used by the machine to represent its value. In such cases, the hill climber may not be able to determine in which direction it should step, and may wander in a direction that never leads to improvement.

Pseudocode

algorithm Discrete Space Hill Climbing is

currentNode := startNode

loop do

L := NEIGHBORS(currentNode)

nextEval := −INF

nextNode := NULL

for all x in L do

if EVAL(x) > nextEval then

nextNode := x

nextEval := EVAL(x)

if nextEval ≤ EVAL(currentNode) then

// Return current node since no better neighbors exist

return currentNode

currentNode := nextNode

algorithm Continuous Space Hill Climbing is

currentPoint := initialPoint // the zero-magnitude vector is common

stepSize := initialStepSizes // a vector of all 1's is common

acceleration := someAcceleration // a value such as 1.2 is common

candidate[0] := −acceleration

candidate[1] := −1 / acceleration

candidate[2] := 0

candidate[3] .= 1 / acceleration

candidate[4] := acceleration

loop do

before := EVAL(currentPoint)

for each element i in currentPoint do

best := −1

bestScore := −INF

for j from 0 to 4 do // try each of 5 candidate locations

currentPoint[i] := currentPoint[i] + stepSize[i] × candidate[j]

temp := EVAL(currentPoint)

currentPoint[i] := currentPoint[i] − stepSize[i] × candidate[j]

if temp > bestScore then

bestScore := temp

best := j

if candidate[best] is 0 then

stepSize[i] := stepSize[i] / acceleration

else

currentPoint[i] := currentPoint[i] + stepSize[i] × candidate[best]

stepSize[i] := stepSize[i] × candidate[best] // accelerate

if (EVAL(currentPoint) − before) < epsilon then

return currentPoint

Contrast genetic algorithm; random optimization.

References

- Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003), Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.), Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, pp. 111–114, ISBN 0-13-790395-2

- Skiena, Steven (2010). The Algorithm Design Manual (2nd ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 1-849-96720-2.

This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Hill climbing |