Affine scaling

In mathematical optimization, affine scaling is an algorithm for solving linear programming problems. Specifically, it is an interior point method, discovered by Soviet mathematician I. I. Dikin in 1967 and reinvented in the U.S. in the mid-1980s.

History

Affine scaling has a history of multiple discovery. It was first published by I. I. Dikin at Energy Systems Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences (Siberian Energy Institute, USSR Academy of Sc. at that time) in the 1967 Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR, followed by a proof of its convergence in 1974.[1] Dikin's work went largely unnoticed until the 1984 discovery of Karmarkar's algorithm, the first practical polynomial time algorithm for linear programming. The importance and complexity of Karmarkar's method prompted mathematicians to search for a simpler version.

Several groups then independently came up with a variant of Karmarkar's algorithm. E. R. Barnes at IBM,[2] a team led by R. J. Vanderbei at AT&T,[3] and several others replaced the projective transformations that Karmarkar used by affine ones. After a few years, it was realized that the "new" affine scaling algorithms were in fact reinventions of the decades-old results of Dikin.[1][4] Of the re-discoverers, only Barnes and Vanderbei et al. managed to produce an analysis of affine scaling's convergence properties. Karmarkar, who had also came with affine scaling in this timeframe, mistakenly believed that it converged as quickly as his own algorithm.[5]:346

Algorithm

Affine scaling works in two phases, the first of which finds a feasible point from which to start optimizing, while the second does the actual optimization while staying strictly inside the feasible region.

Both phases solve linear programs in equality form, viz.

- minimize c ⋅ x

- subject to Ax = b, x ≥ 0.

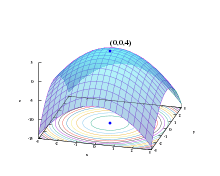

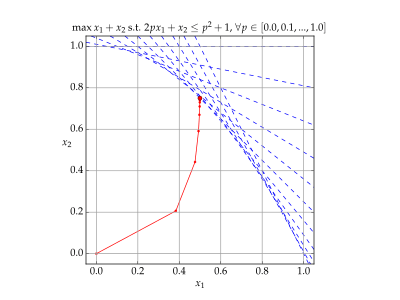

These problems are solved using an iterative method, which conceptually proceeds by plotting a trajectory of points strictly inside the feasible region of a problem, computing projected gradient descent steps in a re-scaled version of the problem, then scaling the step back to the original problem. The scaling ensures that the algorithm can continue to do large steps even when the point under consideration is close to the feasible region's boundary.[5]:337

Formally, the iterative method at the heart of affine scaling takes as inputs A, b, c, an initial guess x0 > 0 that is strictly feasible (i.e., Ax0 = b), a tolerance ε and a stepsize β. It then proceeds by iterating[1]:111

- Let Dk be the diagonal matrix with xk on its diagonal.

- Compute a vector of dual variables:

- Compute a vector of reduced costs, which measure the slackness of inequality constraints in the dual:

- If and , the current solution xk is ε-optimal.

- If , the problem is unbounded.

- Update

Initialization

Phase I, the initialization, solves an auxiliary problem with an additional variable u and uses the result to derive an initial point for the original problem. Let x0 be an arbitrary, strictly positive point; it need not be feasible for the original problem. The infeasibility of x0 is measured by the vector

- .

If v = 0, x0 is feasible. If it is not, phase I solves the auxiliary problem

- minimize u

- subject to Ax + uv = b, x ≥ 0, u ≥ 0.

This problem has the right form for solution by the above iterative algorithm,[lower-alpha 1] and

is a feasible initial point for it. Solving the auxiliary problem gives

- .

If u* = 0, then x* = 0 is feasible in the original problem (though not necessarily strictly interior), while if u* > 0, the original problem is infeasible.[5]:343

Analysis

While easy to state, affine scaling was found hard to analyze. Its convergence depends on the step size, β. For step sizes β ≤ 2/3, Vanderbei's variant of affine scaling has been proven to converge, while for β > 0.995, an example problem is known that converges to a suboptimal value.[5]:342 Other variants of the algorithm have been shown to exhibit chaotic behavior even on small problems when β > 2/3.[6][7]

Notes

- The structure in the auxiliary problem permits some simplification of the formulas.[5]:344

References

- Vanderbei, R. J.; Lagarias, J. C. (1990). "I. I. Dikin's convergence result for the affine-scaling algorithm". Mathematical developments arising from linear programming (Brunswick, ME, 1988). Contemporary Mathematics. 114. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. pp. 109–119. doi:10.1090/conm/114/1097868. MR 1097868.

- Barnes, Earl R. (1986). "A variation on Karmarkar's algorithm for solving linear programming problems". Mathematical Programming. 36 (2): 174–182. doi:10.1007/BF02592024.

- Vanderbei, Robert J.; Meketon, Marc S.; Freedman, Barry A. (1986). "A Modification of Karmarkar's Linear Programming Algorithm" (PDF). Algorithmica. 1 (1–4): 395–407. doi:10.1007/BF01840454.

- Bayer, D. A.; Lagarias, J. C. (1989). "The nonlinear geometry of linear programming I: Affine and projective scaling trajectories" (PDF). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 314 (2): 499. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1989-1005525-6.

- Vanderbei, Robert J. (2001). Linear Programming: Foundations and Extensions. Springer Verlag. pp. 333–347.

- Bruin, H.; Fokkink, R.J.; Gu, G.; Roos, C. (2014). "On the chaotic behavior of the primal–dual affine–scaling algorithm for linear optimization" (PDF). Chaos. 24 (4): 043132. arXiv:1409.6108. Bibcode:2014Chaos..24d3132B. doi:10.1063/1.4902900. PMID 25554052.

- Castillo, Ileana; Barnes, Earl R. (2006). "Chaotic Behavior of the Affine Scaling Algorithm for Linear Programming". SIAM J. Optim. 11 (3): 781–795. doi:10.1137/S1052623496314070.

Further reading

- Adler, Ilan; Monteiro, Renato D. C. (1991). "Limiting behavior of the affine scaling continuous trajectories for linear programming problems" (PDF). Mathematical Programming. 50 (1–3): 29–51. doi:10.1007/bf01594923.

- Saigal, Romesh (1996). "A simple proof of a primal affine scaling method" (PDF). Annals of Operations Research. 62: 303–324. doi:10.1007/bf02206821.

- Tseng, Paul; Luo, Zhi-Quan (1992). "On the convergence of the affine-scaling algorithm" (PDF). Mathematical Programming. 56 (1–3): 301–319. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.94.7852. doi:10.1007/bf01580904. hdl:1721.1/3161.

External links

- "15.093 Optimization Methods, Lecture 21: The Affine Scaling Algorithm" (PDF). MIT OpenCourseWare. 2009.

- Mitchell, John (November 2010). "Interior Point Methods". Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

- "Lecture 6: Interior point method" (PDF). NCTU OpenCourseWare. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-02-06.