Hilarcotherium

Hilarcotherium is an extinct genus of astrapotheriid mammals that lived in South America during the Middle Miocene (Laventan). The type species is H. castanedaii, found in sediments of the La Victoria Formation, part of the Honda Group in the department of Tolima in Colombia.[1] In 2018, Carrillo et al. described a partial skull and mandible of a second species H. miyou from the Castilletes Formation in the Cocinetas Basin of northern Colombia,[2] and estimated the body weight of the animal at 6,465 kilograms (14,253 lb).[3]

| Hilarcotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| The holotype skull of H. castanedaii, in ventral view. Geological Museum José Royo y Gómez, Bogotá | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | †Uruguaytheriinae |

| Genus: | †Hilarcotherium |

| Type species | |

| †Hilarcotherium castanedaii | |

| Species | |

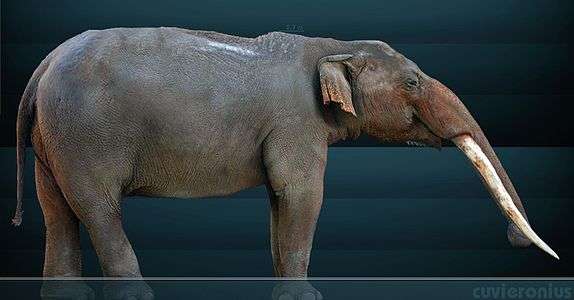

Discovery

The remains of Hilarcotherium castanedaii were discovered by José Alfredo Castañeda, who found them in the Malnombre Creek in the Hilarco village located near the town of Purificación, in Tolima. This area, in the valley of the Upper Magdalena River, correspond to the La Victoria Formation, that along with the Villavieja Formation makes the Honda Group, dating from the Middle Miocene, made between 13-11.8 million years ago and it has provided a remarkable fossil site known as La Venta, although the lack of key fossils does not allow accurate establishment of the membership of the Hilarco site to the formation.[1] The remains of Hilarcotherium were collected by dr. María Páramo and Gerardo Vargas, who took them to the Geological Museum José Royo y Gómez of Ingeominas (former name of Colombian Geological Service) in Bogotá for study and preservation. In February 2015 these remains were officially named, although the name Hilarcotherium castanedaii was released earlier and informally in conference abstracts.[4] The genus name is derived from the Hilarco site and the term in Latinized Greek therium, meaning "beast", while the species name castanedaii is in recognition to Castañeda, by finding and reporting the find.[1]

A second species, H. miyou was described by Carrillo et al. in 2018. The remains of H. miyou were discovered in Patajau, in the Castilletes Formation of La Guajira department, on northern Colombia. The deposits of Castilletes corresponds to the older SALMAs Santacrucian-Colloncuran, 16.7–14.2 million years ago during the early Middle Miocene. The remains the holotype, IGMp 881327, consists on a partial mandible with the left ramus, some of the molars and the canines, the left condylar process, a second upper molar (M2) and the distal portion of the femur. Also were referred to H. miyou the specimens MUN-STRI 34216, a fragmentary skull with portion of the occipitals, palatines, and left upper canine, an upper fourth premolar P4 and the second upper M2, and a fragmentary mandibular symphysis with the base of the lower canines and alveoli for left three incisives (i3, i2, and i1) and the right first incisives (i1 and i2); and MUN-STRI 38073, which consists in a left P4 and upper molar fragments. Also were discovered a series of postcranial remains, including humerus, radii, vertebrae, patella, sacrum, scapulae, femora and rib fragments. Since that these fossils were not associated with dental remains is not possible refer them to H. miyou, but their large size and the fact that Hilarcotherium is the only astrapotherid taxon recognized in Castilletes allow classify them tentatively as Hilarcotherium cf. miyou. The name of this species derived from the word miyo’u that means "large" in the Wayuunaiki language of the Wayuu people of La Guajira.[2]

An additional discovery was made near to the wetlands of Zapatosa, in the municipality of Chimichagua in the Cesar department in northern Colombia. This specimen, a fragment of maxilar with a premolar (P4) and the first upper molar (M1) is catalogued as SGCMGJRG2018.V.7 and is housed in the Geological Museum Jose Royo y Gómez, which were donated by the discoverers of the specimen, Hasmet Florián and José Martínez. The site belongs to the Miocene but without a precise datation; the characteristics of the teeth support the assignation to Hilarcotherium, but since that it shows some differences with the recognised species of the genus, is only classified as Hilarcotherium sp.[5]

Description

The holotype specimen of Hilarcotherium castanedaii is named IGM p881231. This consists of fragments of skull, a partial jaw, the vertebral ramus of a dorsal rib, a complete left humerus and an incisor tooth associated. The skull includes the rostrum area, the palate with the fourth premolar (P4) and the three upper molars (M1-M2-M3) plus part of the zygomatic arch and the braincase, but lacks the upper canines and the top portion of the skull. The premaxilla shows no sign of having teeth, as in other astrapotheres. The jaw missing the incisors, the crown of the fourth premolar and the left mandibular ramus, but has the roots of the teeth of the right side and a broken canine with an oval cross section. It has however the sockets for three incisors on each side of the jaw, which is a plesiomorphic feature, as his other relatives as Xenastrapotherium had two.[1] In 2018, Carillo et al. described a partial skull and mandibule of a second species H. miyou from the Castilletes Formation in the Cocinetas Basin of northern Colombia.[2]

The humerus measures 45 centimetres (1.48 ft), with a head of 84 millimetres (3.3 in) at its widest and oriented backwards with a convex form. Moreover, as in Astrapotherium, the bone thickness decreases as it approaches its lower (distal) end.[1]

Analyses performed with his molars and humerus indicate that weight range of H. castanedaii would be between 1,187 and 1,369 kilograms (2,617 and 3,018 lb), which would be comparable to the modern black rhinoceros. Between astrapotheres, this size is equivalent to an "intermediate" range, since it is greater than that of genus as Comahuetherium (324–504 kilograms (714–1,111 lb)) and Astrapothericulus (956 kilograms (2,108 lb)), and similar to Xenastrapotherium and Astrapotherium? ruderarium, but lower than in the larger genera as Astrapotherium (1,600–3,500 kilograms (3,500–7,700 lb)), Granastrapotherium (3,100 kilograms (6,800 lb)) and Parastrapotherium (3,484–4,117 kilograms (7,681–9,076 lb)) [6] This indicates that the large body size is a trait that developed early in the group, but the gigantic size, of more than 3 tonnes (3.0 long tons; 3.3 short tons), evolved only on three separate occasions.[1] H. miyou had an estimated body weight of 6,465 kilograms (14,253 lb).[3]

Phylogeny

Hilarcotherium belongs to the family Astrapotheriidae, the family of advanced astrapotheres characterized by its developed tusks, separated by a diastema of the other teeth, the retracted nasal bones that indicate the presence of a trunk in his snout and the flattened astragalus. Within this group, Hilarcotherium shares with Xenastrapotherium, Uruguaytherium and Granastrapotherium the lower canines that are horizontally inserted into the jaw, in addition to the characteristics of the molars (without labial cingulum, an inner protuberance of the molars), indicating that Hilarcotherium and the others genera already mentioned belongs to the subfamily Uruguaytheriinae, a group that colonized the equatorial region of South America during the Miocene until their extinction in the middle of such period, in contrast with other astrapotheres only known in the south of the continent.[1]

Cladogram based in the phylogenetic analysis published in the original description article by Vallejo-Pareja et al., 2015, showing the position of Hilarcotherium:[1]

|

Eoastrapostylops | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Vallejo Pareja, M. C.; Carrillo, J. D.; Moreno Bernal, J. W.; Pardo Jaramillo, M.; Rodriguez González, D. F.; Muñoz Duran, J. (2015). "Hilarcotherium castanedaii, gen. et sp. nov., a new Miocene astrapothere (Mammalia, Astrapotheriidae) from the Upper Magdalena Valley, Colombia" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (2): e903960. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.903960.

- Juan D. Carrillo; Eli Amson; Carlos Jaramillo; Rodolfo Sánchez; Luis Quiroz; Carlos Cuartas; Aldo F. Rincón; Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra (2018). "The Neogene record of northern South American native ungulates". Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. 101 (101): iv-67. doi:10.5479/si.1943-6688.101.

- Carillo, 2018, p.142

- Pardo Jaramillo, M.; Rodríguez González, D. F.; Vallejo Pareja, María Camila; Carrillo Sánchez, J. D.; Muñoz Durán, J.; Moreno Bernal, J. W. (2010). Un nuevo género y especie de Astrapotheriidae del Mioceno del Valle Superior del río Magdalena, Colombia [A new genus and species of Miocene astrapotheriidae (from) the upper Magdalena River, Colombia]. X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía-VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de La Plata - Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo.

- Jaramillo, M. P. (2018). Reporte del hallazgo de restos de Hilarcotherium sp.(Mammalia, Astrapotheria) y de material asociado en una nueva localidad fosilífera del valle inferior del Magdalena, ciénaga de Zapatosa, Cesar, Colombi a. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 42(164), 280-286.

- Kramarz, Alejandro G.; Bond, Mariano (2008). "Revision of Parastrapotherium (Mammalia, Astrapotheria) and other Deseadan astrapotheres of Patagonia". Ameghiniana. 45 (3). Retrieved 24 February 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hilarcotherium. |

- Carrillo Sánchez, Juan David. 2018. Systematics of the South American Native Ungulates and the Neogene Evolution of Mammals from Northern South America (PhD thesis), 1–285. University of Zurich. Accessed 2018-05-15.

.jpg)