Le Mans Cathedral

Le Mans Cathedral (French: Cathédrale St-Julien du Mans) is a Catholic church situated in Le Mans, France. The cathedral is dedicated to Saint Julian of Le Mans, the city's first bishop, who established Christianity in the area around the beginning of the 4th century. Its construction dated from the 6th through the 14th century, and it features many French Gothic elements.

| Cathedral of Saint Julian of Le Mans Cathédrale Saint-Julien du Mans | |

|---|---|

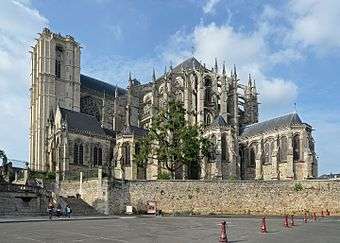

Le Mans Cathedral seen from the southeast (Place des Huguenots) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic Church |

| Province | Diocese of Le Mans |

| Region | Pays de la Loire |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Cathedral |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Le Mans,

France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°0′33″N 0°11′56″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church |

| Style | Roman, French Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 6th century |

| Completed | 14th century |

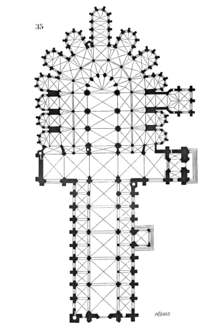

The cathedral, which combines a Romanesque nave and a High Gothic choir, is notable for its rich collection of stained glass and the spectacular bifurcating flying buttresses at its eastern end.

Previous buildings

Nothing is known about the form of the original church founded here by St Julian, which was co-dedicated (as with many early cathedrals) to The Virgin and to St Peter. Although there is no archaeological evidence for the building phases prior to 1080, the history of the bishopric and its cathedral is extensively detailed in the 9th century Actus pontificum Cenomannis in urbe degentium[1] According to this chronicle, in the first half of the 9th century, a major rebuilding of Julian's original cathedral took place under Bishop Aldric.

This new building, designed to house the relics of St Julian, incorporated a large choir (consecrated 834) with an apse and an ambulatory housing five altars – possibly one of the very earliest examples of the chevet-type design that later became a standard for major churches throughout northern Europe. Another remodelling was undertaken throughout the second half of the 11th century (begun under Bishop Vulgrin c.1060, completed under Bishop Hildevert and consecrated 1120).

Current building

The 134 meters long cathedral occupies the northeastern corner of the old town (known as Vieux Mans or the Cité Plantagenêt), an area on top of a slight ridge dominated by cobbled streets and half-timbered houses.

Nave

The current nave is of a typical Romanesque basilica form, with round-arched arcades and single aisles either side of a larger central vessel lit by clerestory windows. Following a fire in 1134, a major rebuilding programme was begun by Bishop Guillaume de Passavant (reg.1142–1186). The new works were partly funded by King Henry II of England, whose father, Geoffroy of Anjou, was buried here in 1151. Whereas the previous buildings had all featured a wooden roof, Bishop Guillaume's new nave, which today survives largely intact, incorporated stone vaults. This feature required considerable thickening of the old walls and the addition of flying buttresses along the flanks of the nave.

The capitals of the nave piers are richly carved, some with classical acanthus leaves, others with more naturalistic vegetation, and incorporating a range of animals and human figures. Around the walls, the springers and corbels are similarly decorated with a rich variety of naturalistic or grotesque (and sometimes humorous) figures.

Choir

In 1217, the cathedral chapter obtained authorisation to demolish part of the 4th-century Gallo-Roman city walls, which had blocked expansion to the east (any modifications to city walls in medieval France required the permission of the king). Work on a greatly enlarged eastern end began immediately, and the new choir was consecrated by Bishop Geoffroy de Loudon on April 24, 1254. In cross-section the new choir closely follows the earlier examples at Bourges Cathedral and Coutances Cathedral, having two aisles (a double ambulatory), with stepped elevations, either side of the central vessel.[2][3] The Le Mans architect combined this Bourges-style design with a number of details borrowed from Chartres cathedral, most notably the elongated chapels radiating from the apse and the treatment of the external flying-buttresses as decorative elements as well as structural supports.[4] The stone carving is generally of a high quality and is highly decorative, particularly in the naturalistic foliage filling the spandrels of the inner arcades.

Seen from the east, the flying buttresses on the outside of the choir present an unusually dense forest of masonry, owing to their unique bifurcating design. Each of the sloping flyers splits in two, presenting a 'Y'-shape in a bird's-eye view, with each arm engaging on a separate upright buttress. Although this design was not taken up elsewhere, it lends an uncharacteristically graceful and delicate feel to the eastern end of the building, especially when seen from the bottom of the hill (at the Place des Huguenots).

Transepts

After the completion of the choir, the next priority was to rebuild the transepts in order to link the new Gothic elements to the Romanesque nave; however, this work was delayed by lack of funds. The south transept, designed by Jean le Maczon, was begun in the 1380s and completed in 1392 with the aid of funds donated by King Charles VI (who had been cared for by the canons of Le Mans Cathedral during one of his bouts of insanity). Work on its northern counterpart began in 1403 but was delayed by a resumption of the Hundred Years War; it was not completed until the 1430s. In 1500, plans to heighten the transepts were abandoned for reasons of cost.[5]

Stained glass

The nave at Le Mans retains around 20 stained glass windows from Bishop Guillaume's mid-12th century rebuilding, though all but one have been moved from their original locations. All very extensively restored in the 19th century.[6] The great western window, depicting scenes from the Life of St Julian of Le Mans, dates from around 1155. The Ascension window, towards the western end of the south aisle of the nave, has been dated to 1120, making it one of the oldest extant stained glass windows in France.[7]

The renowned depiction of Jesus with female characteristics is to be found among the stained glass mosaics in the cathedral.

Unlike the earlier Romanesque windows, the 13th-century glazing programme in the upper parts of the choir is largely intact. It presents a diverse range of scenes from the Old and New Testaments, the Lives of Saints, and various miracles of the Virgin. These windows are notable for their lack of coherent programme (there is no obvious pattern in the distribution of subjects and some episodes, such as the story of Theophilus or the 'miracle of the Jewish boy of Bourges', are repeated in different windows) and for the variety of artistic styles.[8] The windows in the radiating chapels fared less well, and most of the surviving panels have been reassembled out of context in the axial chapel.[9]

Portals

Opening into the south aisle of the nave is an early gothic portal (c.1150), sheltered by a substantial porch that would have provided shelter for ceremonies and processions entering or leaving the cathedral. Stylistically and in its overall design, this portal is closely related to the Portail Royale at Chartres Cathedral and the west facade at the Abbey Church of St Denis, with which it is roughly contemporary. The tympanum features the Majestas Domini (Christ in a mandorla surrounded by the four Evangelist symbols), over the twelve evangelists on the lintel. The doorposts feature St Peter and St Paul (as at Moissac), flanked by eight Old Testament figures on the jamb columns, carved in the hieratic Early Gothic style found at Laon, Chartres (west facade) and in the south portal at Bourges. The archivolts are carved with scenes from the Life of Christ, some of which are squeezed rather awkwardly into the cut-down voussoirs, suggesting they may have originally been intended for a different doorway, or else that the design was changed during construction.[10]

On the right hand corner of the west facade is a 4.5m high prehistoric menhir, locally known as the Pierre St Julien (St Julian's Stone). Natural weathering of the sandstone has given the menhir's surface an unusual appearance, superficially similar to carved drapery. The stone was moved here in 1778, after the dolmen of which it had been part which was demolished.

Burials

References

- Andre Ledru (ed.), Actus pontificum Cenomannis in urbe degentium (Acts of the bishops of Le Mans), Archives Historiques du Maine, Le Mans, 1901

- Joel Herschman, "The Norman Ambulatory of Le Mans Cathedral and the Chevet of the Cathedral of Coutances", in Gesta, Vol. 20, No. 2, 1981, pp.323-32.

- For the specific influences of Bourges, see Robert Branner, The Cathedral of Bourges and Its Place in Gothic Architecture, 1963, p.184ff

- Jean Bony, French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, 19xx, p.256ff

- A. Mussat, La Cathedrale du Mans, Paris, 1981

- Louis Grodecki, Les Vitraux de la cathédrale du Mans, Congress Archéologique de France, Vol.119, 1961, pp.59–99

- See Caroline Brissac's article in A. Mussat (ed.), La Cathédrale du Mans, Paris, 1981

- For images of all the triforium/clerestory windows see; http://www.medievalart.org.uk/LeMans/LeMans_default.htm

- The only monograph on the windows is Emile Hucher's physically unwieldy and difficult to find Calques des vitraux de la cathédrale du Mans, Le Mans, 1855–62

- Thomas Polk, The South Portal of the Cathedral at Le Mans: Its Place in the Development of Early Gothic Portal Composition, Gesta, 24:1 (1985), pp.47–60

See also

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Le Mans Cathedral. |