Hasselt dialect

Hasselt dialect or Hasselt Limburgish (natively Essels or Hessels,[3] Standard Dutch: Hasselts [ˈɦɑsəlts]) is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Belgian city of Hasselt alongside the Dutch language. All of its speakers are bilingual with standard Dutch.[2]

| Hasselt dialect | |

|---|---|

| Essels, Hessels | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈʔæsəls], [ˈhæsəls][1] |

| Native to | Belgium |

| Region | Hasselt |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Dorsal | Postalveolar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive / Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | x | ʃ | h |

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | |||

| Rhotic | r | |||||

| Approximant | β | l | j | |||

- Obstruents are devoiced word-finally. However, when the next word starts with a vowel and is pronounced without a pause, both voiced and voiceless word-final obstruents are realized as voiced.[1]

- /m, p, b, β/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.[2]

- The sequences /nt, nd/ are realized as more or less palatalized:

- /p, b, t, d, k/ are plosives, whereas /dʒ/ is an affricate.[2]

- /ŋ, k, x, ɣ/ are velar, whereas /j/ is palatal.[2]

- /r/ is either alveolar or, more commonly, uvular - see below.

- Word-initial /h/ is often realized as a plosive [ʔ].[1]

Realization of /r/

According to Peters (2006), /r/ is realized as a voiced trill, either alveolar [r] or uvular [ʀ]. Between vowels, it is sometimes realized with one contact (i.e. as a tap) [ɾ ~ ʀ̆],[1] whereas word-finally, it can be devoiced to [r̥ ~ ʀ̥].[4]

According to Sebregts (2014), about two thirds of speakers have a uvular /r/, whereas about one third has a categorical alveolar /r/. There are also a few speakers who mix uvular and alveolar articulations.[5]

Among uvular articulations, he lists uvular trill [ʀ], uvular fricative trill [ʀ̝], uvular fricative [ʁ] and uvular approximant [ʁ̞], which are used more or less equally often in all contexts. Almost all speakers with a uvular /r/ use all four of these realizations.[6]

Among alveolar articulations, he lists alveolar tap [ɾ], voiced alveolar fricative [ɹ̝], alveolar approximant [ɹ], partially devoiced alveolar trill [r̥], voiceless alveolar trill [r̥], alveolar tapped or trilled fricative [ɾ̞ ~ r̝], voiceless alveolar tap [ɾ̥] and voiceless alveolar fricative [ɹ̝̊]. Among these, the tap is most common, whereas the taped/trilled fricative is the second most common realization. The partially devoiced alveolar trill occurred only once.[6]

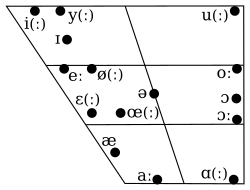

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | u | uː |

| Close-mid | ɪ | eː | ø | øː | (oː) | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | œ | œː | ɔ | ɔː |

| Open | æ | aː | ɑ | ɑː | ||

| Unstressable | ə | |||||

- There are also the nasal vowels /œ̃ː, ɔ̃ː, æ̃ː, ɑ̃ː/, which occur only in French loanwords.[8]

- /aː/ is near-front [a̠ː].[8]

- All of the back vowels are almost fully back.[7] Among these, /u, uː, oː, ɔ, ɔː/ are rounded, whereas /ɑ, ɑː/ are unrounded.

- /oː/ is a marginal vowel. Its occurrence is restricted to loanwords from standard Dutch and English.[8]

- Before alveolar consonants, the long rounded vowels /uː, øː, œː/ are realized as centering diphthongs [uə, øə, œə].[8]

- /ə, ɔ/ are mid [ə, ɔ̝].[8]

- /ə/ occurs only in unstressed syllables.[1]

- /æ/ is near-open, whereas /aː, ɑ, ɑː/ are open.[8]

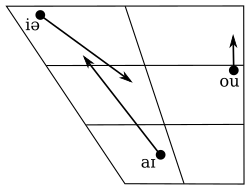

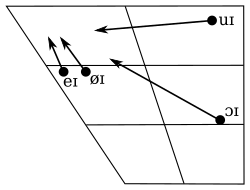

| Starting point | Ending point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | ||

| Close | uɪ | iə | ||

| Close-mid | unrounded | eɪ | ||

| rounded | øɪ | ou | ||

| Open-mid | ɔɪ | |||

| Open | aɪ | |||

- /iə, øɪ, aɪ/ have somewhat retracted first elements [i̠, ø̠, a̠]. In the case of /aɪ/, its first element is also somewhat raised. Because of that, it is best described as near-open advanced central [ɐ̟].[8]

- /aɪ/ and occurs only in loanwords from French and interjections.[8]

- /uɪ/ and /ɔɪ/ have somewhat advanced first elements ([u̟] and [ɔ̟], respectively).[8]

- Before alveolar consonants, /eɪ, ou/ are realized as centering diphthongs [eə, oə]. In the case of /eɪ/, this happens only before the sonorants, i.e. /n, l/ and the alveolar allophones of /r/, with the triphthong [ejə] being an alternative pronunciation. In the case of /ou/, the centering diphthong is used before all alveolar consonants, not just the sonorants. No triphthongal variants of /ou/ have been reported.[8]

- /øɪ, ɔɪ, aɪ/ occur only word-finally.[8]

- /ou, ɔɪ, aɪ/ have somewhat lowered second elements [u̞, ɪ̞, ɪ̞].[8]

There are also the sequences /uːj, ɔːj, ɑːj/, which are better analyzed as sequences of /uː, ɔː, ɑː/ and the approximant /j/, rather than diphthongs /uːi, ɔːi, ɑːi/. The sequences /ɔːj, ɑːj/ occur only word-finally.[8]

References

- Peters (2006), p. 118.

- Peters (2006), p. 117.

- Staelens (1989).

- Peters (2006). While the author does not state that explicitly, he uses the symbol ⟨r̥⟩ for many instances of the word-final /r/.

- Sebregts (2014), p. 96.

- Sebregts (2014), p. 97.

- Peters (2006), pp. 118–119.

- Peters (2006), p. 119.

Bibliography

- Peters, Jörg (2006), "The dialect of Hasselt", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (1): 117–124, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002428

- Sebregts, Koen (2014), "3.4.4 Hasselt", The Sociophonetics and Phonology of Dutch r (PDF), Utrecht: LOT, pp. 96–99, ISBN 978-94-6093-161-1

- Staelens, Xavier (1989), Dieksjenèèr van 't (H)essels (3rd ed.), Hasselt: de Langeman

Further reading

- Grootaers, Ludovic; Grauls, Jan (1930), Klankleer van het Hasseltsch dialect, Leuven: de Vlaamsche Drukkerij

- Peters, Jörg (2008), "Tone and intonation in the dialect of Hasselt", Linguistics, 46 (5): 983–1018, doi:10.1515/LING.2008.032, hdl:2066/68267