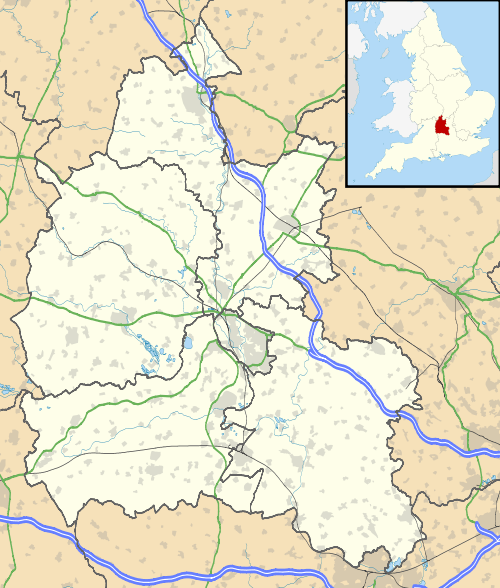

Hanwell, Oxfordshire

Hanwell is a village and civil parish in Oxfordshire, about 2 miles (3 km) northwest of Banbury. Its area is 1,240 acres (500 ha) and its highest point is about 500 feet (150 m) above sea level.[1] The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 236.[2]

| Hanwell | |

|---|---|

St Peter's parish church | |

Hanwell Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Area | 4.30 km2 (1.66 sq mi) |

| Population | 263 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 61/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SP4343 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Banbury |

| Postcode district | OX17 |

| Dialling code | 01295 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Hanwell Village Oxfordshire |

Early history

Remains of a substantial Roman villa have been found just west of the B4100 main road.[1][3]

Hanwell village is Saxon in origin, on an ancient minor road linking the villages of Wroxton and Great Bourton. The road's Old English name of Hana's weg gave rise to the village's toponym. Hanwell has a reliable spring, so its toponym later changed from -weg to -welle.[1]

Manor

Before the Norman conquest of England an Anglo-Saxon called Lewin or Leofwine held the manor of Hanwell, along with those of Chinnor and Cowley. Whereas the conquering Normans dispossessed many Saxon landowners after 1066, Leofwine still held Hanwell manor by the time the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086. The de Vernon family held the manors of Hanwell and Chinnor, and retained Hanwell until 1415 when Sir Richard de Vernon transferred the manor to Thomas Chaucer, Speaker of the House of Commons of England. After Chaucer's death in 1434 Hanwell passed to his widow Maud and then their daughter Alice de la Pole. Alice's second husband was William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, and Hanwell remained with the Duchy of Suffolk until almost the end of the 15th century.[1]

In 1498 Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk conveyed the manor to William Cope, who was Cofferer to Henry VII. In 1611 James I made William's great-grandson Anthony Cope a baronet. Hanwell remained with the Cope baronets of Hanwell until the death of Sir John Cope, 5th Baronet in 1721. It then passed to another branch of the Cope family, Sir Jonathan Cope, 1st Baronet of Bruern. When Sir Charles Cope, 3rd Baronet died in 1781, Hanwell passed to one of his sisters, Catherine.[1]

In 1790 Catherine's daughter Arabella was married to John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset and received Hanwell from her mother. In 1825 Hanwell was inherited by the Duke and Duchess's younger daughter, Elizabeth Sackville-West, Countess De La Warr, wife of George Sackville-West, 5th Earl De La Warr. Hanwell manor has remained with the Earls De La Warr: in 1946 Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr passed the manor to his son Lord Buckhurst, the future William Sackville, 10th Earl De La Warr.[1]

Church and chapel

Church of England

The earliest record of the Church of England parish church of Saint Peter is from 1154, but only the Norman font survives from this time. The north and south doorways are 13th century, the east window of the south aisle are late 13th century, and all are Early English Gothic. In the first half of the 14th century St. Peter's was almost entirely rebuilt in a Transitional style between Early English and Decorated Gothic, and north and south aisles and the Decorated Gothic bell tower were added. The arcades linking the aisles with the nave have capitals decorated with carved figures[4] and the chancel has a frieze of carved people and monsters. Both sets of carvings were made in about 1340 and are the work of a school of masons whose work can be seen also in the parish churches of Adderbury, Bloxham and Drayton. Around 1400 a Perpendicular Gothic clerestory was added to the nave. In the Tudor era new side windows were inserted in the north aisle.[3][1]

Monuments in St. Peter's include a 14th-century effigy of a woman in the south aisle and effigies of Sir Anthony Cope, 1st Baronet (died 1614) and his wife in the chancel. In 1776 the floor of the chancel was raised to accommodate a burial vault for the Cope family, but in the 19th century the floor was restored to its former level[1]

In 1671 Sir Anthony Cope, 4th Baronet had a turret clock made for St. Peter's by the noted clockmaker George Harris of Fritwell.[5] It is at the west end of the nave below the bell tower. The bell tower has a ring of six bells. John Briant of Hertford[6] cast the second, third, fourth and fifth bells in 1789 and the tenor bell in 1791.[7] In 2008 White's of Appleton re-hung the bells and added a sixth bell, the Beecroft Bell which Whitechapel Bell Foundry had cast that year.[7]

Sir Anthony Cope, 1st Baronet (1550–1615) was a puritan, and in 1584 the Church of England excommunicated his choice of curate at Hanwell, Jonas Wheler for refusing to hold church services on Fridays and Saturdays. Instead therefore Sir Anthony presented John Dod, another puritan, who was accepted. Dod was a friend of the puritan divine Thomas Cartwight, who at Dod's invitation preached at Hanwell. Sir Anthony was MP for the Banbury constituency for most of the period 1571–1601. In 1587 he was jailed for introducing to the House of Commons a puritan prayer book and a bill for abrogating ecclesiastical law. John Dod was a hardworking and popular preacher who served as Hanwell for 20 years, but by 1607 the Church of England had deprived Dod of his living and Sir Anthony appointed Robert Harris to take over the curacy. During the English Civil War Royalist troops had expelled Harris from Hanwell by the end of 1642. In 1648 he was made a Doctor of Divinity and President of Trinity College, Oxford. Puritan influence at Hanwell was ended in 1658 with the appointment of a Royalist curate, George Ashwell, who was as pious, hardworking and scholarly as his predecessors.[1]

St Peter's is now a Grade I listed building.[8] Its parish is now one of eight in the Ironstone Benefice.[9]

Hanwell Castle

Hanwell Castle was not a castle but a house with ornamental battlements, originally called Hanwell House or Hall. William Cope began building it in 1498, the year he had received the manor of Hanwell from the Duke of Suffolk. It is the earliest example of a brick building in north Oxfordshire. It was a large house with west, north and south ranges around a central quadrangle. Jennifer Sherwood and Nikolaus Pevsner contend that there was an east range[3] but Mary Lobel et al.[1] maintain that there was none. The house has fishponds fed by the village spring.

The Cope family had links with Catherine Parr (1512–48), the sixth and last wife of Henry VIII.[10] Sir Anthony Cope, 1st Baronet entertained James I at Hanwell House in 1605 and 1612, and at the castle Sir William Cope, 2nd Baronet entertained James I in 1616 and Charles I in 1637.[1]

Late in the 18th century most of Hanwell Castle was demolished. The western part of the south range was retained as a farmhouse, and in 1902 some restoration and extensions were made to the surviving building.[3] It is now a Grade II* listed building.[11]

In 2015 renovation work at Tudor Cottage in the village revealed the broken remains of a stone relief of a Tudor coat of arms believed to have come from the castle. The relief is finely carved from clunch and is described as being of "national importance", but has not been dated with certainty as parts are missing.[10]

The cricket player George Berkeley lived at the castle until his death in 1955.[12]

Astronomical observatory

Hanwell Community Observatory is in the castle grounds, which are a dark site for astronomy. The observatory was founded in 1992 and the grounds are open to the public at the observatory's annual open weekend every February.[13] Note added 22.2.16 by Christopher Taylor, Director (and founder) of Hanwell Community Observatory: 1992 was the year that my own 12.5-inch reflector, the McIver Paton Telescope, was re-erected in the grounds at Hanwell, and serious astronomy began here. The Hanwell Community Observatory was begun on the same site in 1999, following a successful bid for a Royal Society Millennium Award for public outreach in astronomy the previous autumn.

Social and economic history

By the 13th century Hanwell had a watermill on the western edge of the parish, presumably on Sor Brook that forms the boundary with the adjoining parish of Horley. Before 1249 Sir Warin de Vernon granted the mill to the Augustinian canons of Canons Ashby Priory in Northamptonshire, who then rented or leased it out until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536. The mill then became Crown property until it was sold in 1545.[1]

Hanwell rectory dates from at least the 16th century. There is a record of it being leased in 1549, at which time it had one or more dovecotes. When it was assessed for hearth tax it was a large house, second in Hanwell only to the manor house. It was reduced in size and the remainder rebuilt in 1843, but parts of the original house survive in the Victorian building.[1]

At the end of the 16th century Hanwell's crops included not only wheat, pease, oats and barley but also at least 100 acres (40 ha) of woad. In 1645 during the English Civil War, Parliamentary troops were billeted in Hanwell for nine weeks and villagers petitioned the Warwickshire Committee of Accounts to pay for feeding them. Villagers farmed the parish on a two-field open field system until 1768, when Sir Charles Cope, 2nd Baronet bought out the rights of copyholders, life- and leaseholders and enclosed the common lands.[1]

The main road between Banbury and Warwick runs north – south along a ridge in the western part of the parish. It was made into a turnpike in 1744 and ceased to be one in 1871.[1] In the 1920s it was classified as part of the A41 road. After the completion of the M40 motorway in 1990 this part of the A41 was "detrunked" and reclassified as the B4100.

Hanwell had a public house, the Red Lion, by 1792.[1] It is now a gastropub, the Moon and Sixpence,[14] controlled by Wells & Young's Brewery.

In 1848 George Sackville-West, 5th Earl De La Warr gave a cottage to be used as both the schoolroom and schoolmaster's house. In 1868 a National School was built and the cottage became exclusively the schoolmaster's home. The school must have proved unsatisfactory, for in 1872 it was forced to become a board school. By 1952 the school had only 17 children and in 1961 it was closed.[1]

References

- Lobel & Crossley 1969, pp. 112–123.

- "Area: Hanwell (Parish): Parish Headcounts: Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 631–632.

- Oxfordshire Churches website: Hanwell St Peter Archived 4 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine: photographs of carved capitals

- Beeson & Simcock 1989, p. 39.

- Dovemaster (25 June 2010). "Dove Founders". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- Davies, Peter (20 June 2010). "Hanwell S Peter". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Historic England. "Church of St Peter (Grade I) (1216364)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "St Peter's Church Hanwell". The Ironstone Benefice Churches. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- "'Wolf Hall' coat of arms found in Hanwell Tudor cottage". Banbury Guardian. Johnston Press. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Historic England. "Hanwell Castle (Grade II*) (1287674)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "Obituaries: Mr G. Fitz-H. Berkeley". The Times (53383). London. 21 November 1955. p. 12.

- "About Us". Hanwell Community Observatory. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Hylton's at the Moon and Sixpence". Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

Sources

- Beeson, C.F.C. (1989) [1962]. Simcock, A.V (ed.). Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400–1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. p. 39. ISBN 0-903364-06-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lobel, Mary D; Crossley, Alan, eds. (1969). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. 9: Bloxham Hundred. London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 112–123. ISBN 978-0-19722-726-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 631–632. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()