Yumi

Yumi (弓) is the Japanese term for a bow. As used in English, yumi refers more specifically to traditional Japanese asymmetrical bows, and includes the longer daikyū (大弓) and the shorter hankyū (半弓) used in the practice of kyūdō and kyūjutsu, or Japanese archery. The yumi was an important weapon of the samurai warrior during the feudal period of Japan. It shoots Japanese arrows called ya.

History

Early Japanese used bows of various sizes but the majority were short with a center grip. This bow was called the maruki yumi and was constructed from a small sapling or tree limb. It is unknown when the asymmetrical yumi came into use, but the first written record is in the Book of Wei, a Chinese historical manuscript from the 3rd century AD, which describes the people of the Japanese islands using "spears, shields, and wooden bows for arms; the wooden bows are made with the lower limbs short and the upper limbs long; and bamboo arrows with points of either iron or bone."[1] The oldest asymmetrical yumi found to date was discovered in Nara and is estimated to be from the 5th century.[2]

During the Heian period (794-1185) the length of the yumi was fixed at a little over two meters and the use of laminated construction was adopted from the Chinese. By the end of the 10th century the Japanese developed a two piece bamboo and wood laminated yumi. Over the next several hundred years the bow's construction evolved and by the 16th century the design was considered to be nearly perfect. The modern bamboo yumi is practically identical to the yumi of the 16th and 17th centuries.[3]

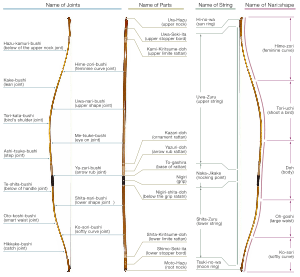

Shape

The yumi is exceptionally tall, standing over two meters, and typically surpasses the height of the archer (ite, 射手).[4] They are traditionally made by laminating bamboo, wood and leather, using techniques which have not changed for centuries, although some archers (particularly beginners) may use a synthetic yumi.

The yumi is asymmetric; According to the All Nippon Kyudo Federation, the grip (nigiri) has to be positioned at about two thirds of the distance from the upper tip.

The upper and lower curves also differ. Several hypotheses have been offered for this asymmetric shape. Some believe it was designed for use on a horse, where the yumi could be moved from one side of the horse to the other with ease, however there is evidence that the asymmetrical shape predates its use on horseback.[5]

Others claim that asymmetry was needed to enable shooting from a kneeling position. Yet another explanation is the characteristics of the wood from a time before laminating techniques. In case the bow is made from a single piece of wood, its modulus of elasticity is different between the part taken from the treetop side and the other side. A lower grip balances it.

The hand holding the yumi may also experience less vibration due to the grip being on a vibration node of the bow. A perfectly uniform pole has nodes at 1/4 and 3/4 of the way from the ends, or 1/2 if held taut at the ends – these positions will change significantly with shape and consistency of the bow material.

String

The string of a yumi is traditionally made of hemp, although most modern archers will use strings made of synthetic materials such as Kevlar, which will last longer. Strings are usually not replaced until they break; this results in the yumi flexing in the direction opposite to the way it is drawn, and is considered beneficial to the health of the yumi. The nocking point on the string is built up through the application of hemp and glue to protect the string and to provide a thickness which helps hold the nock (hazu) of the arrow (ya) in place while drawing the yumi. But can also be made of strands of waxed bamboo.

Care and maintenance

A bamboo yumi requires careful attention. Left unattended, the yumi can become out-of-shape and may eventually become unusable. The shape of a yumi will change through normal use and can be re-formed when needed through manual application of pressure, through shaping blocks, or by leaving it strung or unstrung when not in use.

The shape of the curves of a yumi is greatly affected by whether it is left strung or unstrung when not in use. The decision to leave a yumi strung or unstrung depends upon the current shape of the yumi. A yumi that is relatively flat when unstrung will usually be left unstrung when not in use (a yumi in this state is sometimes referred to as being 'tired'). A yumi that has excessive curvature when unstrung is typically left strung for a period of time to 'tame' the yumi.

A well cared-for yumi can last many generations, while the usable life of a mistreated yumi can be very short.

Bow lengths

| Height of archer | Arrow length | Suggested bow length |

|---|---|---|

| < 150 cm | < 85 cm | Sansun-zume (212 cm) |

| 150–165 cm | 85–90 cm | Namisun (221 cm) |

| 165–180 cm | 90–100 cm | Nisun-nobi (227 cm) |

| 180–195 cm | 100–105 cm | Yonsun-nobi (233 cm) |

| 195–205 cm | 105–110 cm | Rokusun-nobi (239 cm) |

| > 205 cm | > 110 cm | Hassun-nobi (245 cm) |

Yumi history

| Time Period | Type of Bow | Bow Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Prehistoric | Maruki | Single piece of wood |

| c.800-900 | Fusetake | Wood with bamboo front |

| c.1100 | Sanmaiuchi | Wood with bamboo front and back |

| c.1300–1400 | Shihochiku | Wood surrounded with bamboo |

| c.1550 | Sanbonhigo (Higoyumi) | Three-piece bamboo laminate core, wooden sides, bamboo front and back |

| c.1600 | Yohonhigo (Higoyumi) | Four-piece bamboo laminate core, wooden sides, bamboo front and back |

| c.1650 | Gohonhigo (Higoyumi) | Five-piece bamboo (or bamboo and wood) laminate core, wooden sides, bamboo front and back |

| c.1971-Modern times | Glass fiber | Wooden laminate core, FRP front and back |

The Korekawa bow, from the late Jōmon period which ended about 400 BCE, is laminated.[6]

Gallery

.jpg) Moto hazu (bottom nock)

Moto hazu (bottom nock).jpg) Nigiri (grip)

Nigiri (grip).jpg) :Ura hazu (top nock)

:Ura hazu (top nock)- Tsurumaki (string holder) and tsuru (string)

_hanky%C5%AB(small_yumi).jpg) Antique hankyū (shortbow)

Antique hankyū (shortbow)_daiky%C5%AB_and_hanky%C5%AB_yumi_3.jpg) Antique daikyū (longbow) and hankyū (shortbow)

Antique daikyū (longbow) and hankyū (shortbow)_yumi_bukuro.jpg) Yumi bukuro (cloth cover)

Yumi bukuro (cloth cover) Ukiyo-e by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi depicting Minamoto no Tsunemoto hunting a sika deer with a yumi.

Ukiyo-e by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi depicting Minamoto no Tsunemoto hunting a sika deer with a yumi.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yumi. |

- Kyūdō (弓道) -- "Way [of the] Bow".

- Kyūjutsu (弓術) -- "Bow Technique".

- Daikyū (大弓) -- a "Great Bow", a long bow.

- Hankyū (半弓) -- a "Half Bow", a short bow.

- Azusa Yumi (梓弓) -- a "Catalpawood Bow".

- Hama Yumi (破魔弓) -- an "Evil-Destroying Bow".

- Saigū Yumi (祭宮弓) -- a "Ceremonial Bow".

- Ya (arrow) (矢) -- an Arrow.

References

- Records of the Three Kingdoms, Book of Wei: 兵用矛楯木弓木弓短下長上竹箭或鐵鏃或骨鏃

- Kyudo: the essence and practice of Japanese archery, Hideharu Onuma, Dan DeProspero, Jackie DeProspero, Kodansha International, 1993 P.37

- Kyudo: the essence and practice of Japanese archery, Hideharu Onuma, Dan DeProspero, Jackie DeProspero, Kodansha International, 1993 P.40

- Onuma, Hideharu (1993). Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery (1 ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd. p. 43. ISBN 978-4-7700-1734-5.

- Friday, Karl (2004). Samurai, Warfare and the State in Early Medieval Japan. New York NY: Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-415-32962-0.

- The Korekawa bow at Nara National Museum Accessed 2007-06-15 Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Herrigel, Eugen (1999). Zen in the Art of Archery. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-70509-0.

- Michael, Henry N. (1958). "The Neolithic Age in Eastern Siberia". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society (published April 1958). 49 (2): 1–108. doi:10.2307/1005699. hdl:2027/mdp.39015018658560. JSTOR 1005699.