HMS Emerald (1795)

HMS Emerald was a 36-gun Amazon-class frigate that Sir William Rule designed in 1794 for the Royal Navy. The Admiralty ordered her construction towards the end of May 1794 and work began the following month at Northfleet dockyard. She was completed on 12 October 1795 and joined Admiral John Jervis's fleet in the Mediterranean.

Emerald | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Emerald |

| Ordered: | 24 May 1794 |

| Builder: | Thomas Pitcher |

| Cost: | £14,419 |

| Laid down: | June 1794 |

| Launched: | 31 July 1795 |

| Commissioned: | August 1795 |

| Fate: | Broken up, January 1836 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type: | Amazon-class fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen: | 933 67⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 38 ft 4 in (11.7 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 13 ft 6 in (4.1 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Complement: | 264 |

| Armament: |

|

In 1797, Emerald was one of several vessels sent to hunt down and capture the crippled Santisima Trinidad, which had escaped from the British at the Battle of Cape St Vincent. Emerald was supposed to have been present at the Battle of the Nile but in May 1798 a storm separated her from Horatio Nelson's squadron and she arrived in Aboukir Bay nine days too late. She was part of Rear-Admiral John Thomas Duckworth's squadron during the action of 7 April 1800 off Cádiz.

Emerald served in the Caribbean throughout 1803 in Samuel Hood's fleet, then took part in the invasion of St Lucia in July, and of Surinam the following spring. Returning to home waters for repairs in 1806, she served in the Western Approaches before joining a fleet under Admiral James Gambier in 1809, and taking part in the Battle of the Basque Roads. In November 1811 she sailed to Portsmouth where she was laid up in ordinary. Fitted out as a receiving ship in 1822, she was eventually broken up in January 1836.

Construction

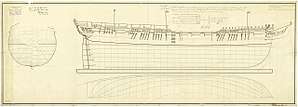

Emerald was a 36-gun, 18-pound, Amazon-class frigate built to William Rule's design.[Note 1][1] She and her sister ship, Amazon, were ordered on 24 May 1794 and were built to the same dimensions: 143 feet 2 1⁄2 inches (43.6 m) along the gun deck, 119 feet 5 1⁄2 inches (36.4 m) at the keel, with a beam of 38 feet 4 inches (11.7 m) and a depth in the hold of 13 feet 6 inches (4.1 m). They measured 933 67⁄94 tons burthen.[1]

Emerald was completed at Thomas Pitcher's dockyard in Northfleet at a cost of £14,419 and launched on 31 July 1795, twenty-seven days after Amazon. Her coppering at Woolwich was finished on 12 October 1795, and she was fitted-out at a further cost of £9,390.[1] The Admiralty ordered a second pair of Amazon-class ships on 24 January 1795. They were marginally smaller at 92587⁄94 tons (bm) and were built from pitch pine.[1][Note 2]

Service

Mediterranean

Emerald was first commissioned in August 1795, under Captain Velters Cornewall Berkeley and in January 1797, she sailed for the Mediterranean.[1] Spain had become allied to France and declared war on Britain in October 1796. Early in 1797, a Spanish fleet of 27 ships of the line was at Cartagena with orders to join the French fleet at Brest. A storm blew the Spanish fleet off course, enabling Admiral John Jervis's fleet of 15 ships of the line to intercept it off Cape St Vincent on 14 February.[4] Although attached to Jervis' fleet at the time, as a frigate Emerald was too lightly built to take part in the Battle of Cape St Vincent; instead she anchored in nearby Lagos Bay with other vessels.[1][5]

On 16 February, the victorious British fleet and its prizes entered the bay. Jervis ordered the three frigates—Emerald, Minerve and Niger, of 40 and 32 guns, respectively—to search for the disabled flagship, Santisima Trinidad, which had been towed from the battle. Two smaller craft—Bonne-Citoyenne, a corvette of 20 guns, and the 14-gun sloop Raven—joined the frigates.[1][5] The British squadron on 20 February sighted Santisima Trinidad under tow by a large frigate and in the company of a brig. Berkeley, considering the small squadron under his command insufficient, declined to engage and eventually the Spanish ships sailed from sight.[Note 3] The 32-gun HMS Terpsichore, while cruising alone, later located Santisima Trinidad and engaged her but the out-gunned British frigate was forced to abandon her attack.[5]

Action of 26 April 1797

Following the Battle of Cape St Vincent, the British pursued the remainder of the Spanish fleet to Cádiz, where Jervis began a long-running blockade of the port.[7] On 26 April, while cruising in the company of the 74-gun Irresistible, Emerald helped to capture a 34-gun Spanish ship and to destroy another.[8] The Spanish vessels were close to the coast when Jervis's fleet sighted them. Sent to investigate, Emerald and Irresistible, under Captain George Martin, discovered the ships were the frigates Santa Elena and Ninfa[9]—the Spanish ships had been carrying silver from Havana to Cádiz, but had transferred their cargo the previous night to a fishing boat that had warned them of the proximity of the British fleet.[8]

The Spanish ships sought shelter from the British north of Trafalgar in Conil Bay, the entrance to which was protected by a large rocky ledge. Irresistible and Emerald negotiated this obstacle at around 14:30 and engaged the Spanish ships, which were anchored in the Bay.[10][11] The Spanish ships surrendered at approximately 16:00. Eighteen Spaniards were killed and 30 wounded during the fighting; one Briton was killed and one wounded.[11] The remaining crew of Santa Elena avoided capture by cutting her cables and drifting her on shore so they could flee on foot. The British managed to drag Santa Elena off the beach but, badly damaged, she sank at sea.[10][11]

The British took Ninfa into service as HMS Hamadryad, a 36-gun frigate with a main battery of 12-pounders,[9][12] but were unable to retrieve the cargo of silver, which later arrived safely in Cádiz.[8]

Second bombardment of Cádiz

Captain Thomas Waller took command of Emerald in mid-1797, and was stationed with Admiral Jervis's fleet off Cádiz.[1][13] On 3 July, Jervis attempted to end the protracted blockade by ordering a bombardment of the town. A first attempt resulted in the capture of two Spanish mortar boats but achieved little else.[14] During a second bombardment on the night of 5 July, Emerald, in the company of Terpsichore and the 74-gun Theseus, provided a protective escort for three bomb vessels, Thunder, Terror and Strombolo. This attack caused considerable damage; the next morning, the Spanish hurriedly moved ten of their line-of-battle ships out of range.[15] The British cancelled a third bombardment, planned for 8 July, when the weather became unfavourable.[13][15]

Attack on Santa Cruz

Later in July 1797, Emerald took part in an unsuccessful attack on Santa Cruz.[1] A planned attack in April, proposed by Admiral Nelson, had been aborted as the troops required to execute it were unavailable. When Jervis was subsequently advised that the Spanish treasure fleet was anchored there, he revived Nelson's idea.[16]

For the new attack, Nelson was to take three ships of the line, three frigates, including Emerald, and 200 marines, for an amphibious landing outside the Spanish stronghold.[1][16] The frigates would then engage the batteries to the north-east of Santa Cruz while the marines stormed the town. However, a combination of strong currents and heavy Spanish fire forced the British to abandon the attack. Several further attempts were made between 22 and 25 July; although the British were able to land troops, Spanish resistance was too strong and the British had to ask for an honourable withdrawal.[17] Here one of the flags of the HMS Emerald was captured and it is now in display at the Museo Histórico Militar de Canarias.

After the attack, Nelson sent Emerald with his report to Jervis, who in turn sent her on to England with dispatches. Waller arrived at the Admiralty on 1 September, with the news of the failed attacks.[18]

Alexandria

While serving with Jervis on the Lisbon station in December 1797, Emerald, under the temporary command of Lord William Proby, captured the 8-gun privateer, Chasseur Basque. Waller returned as captain in April 1798.[1] In May, Jervis dispatched a squadron of five ships, including Emerald and commanded by Nelson in the 74-gun Vanguard, to locate a large invasion fleet that had left Toulon.[19][Note 4] After receiving intelligence on 22 May, Nelson correctly predicted the French fleet's destination and set course for Alexandria[20] where the British captured or destroyed all but two of the French ships at the Battle of the Nile, which occurred between 1–3 August 1798.[21] Emerald missed the battle; having previously become separated from the rest of the squadron in a storm on 21 May,[19] she arrived at Aboukir Bay on 12 August.[22]

When Nelson left for Naples on 19 August 1798, he left behind a squadron—comprising three 74s Zealous, Goliath, Swiftsure, three frigates Emerald, Seahorse and Alcmene, and the corvette Bonne Citoyenne—under Samuel Hood to patrol the waters around the port and along the coast.[23] On 2 September, it encountered and destroyed the French aviso Anémone.[Note 5][25]

Emerald and Seahorse chased Anemone inshore, where she anchored in shallow water out of their reach. When they launched their boats to cut-out Anėmone, her crew cut the anchor cable and their ship drifted on to the shore; as the Frenchmen were attempting to escape along the coast, hostile Arabs captured them and stripped them of their clothes, shooting those who resisted. A heavy surf prevented the British boats from landing, so a midshipman from Emerald, the young Francis Fane, swam ashore with a line and empty cask to rescue the commander and seven others who had escaped naked to the beach.[25][26][Note 6] Anėmone had a crew of 60 men under the command of Enseigne de Vaisseau (Ensign) Garibou,[28] and was also carrying General Camin and Citoyen Valette, aide-de-camp to General Napoleon Bonaparte, with dispatches from Toulon. Camin and Valette were among those the Arabs killed.[25][Note 7] Emerald remained stationed off Alexandria for the rest of the year.[1]

Action on 18 June 1799

Emerald and Minerve, while cruising together on 2 June, took Caroline, a 16-gun French privateer, off the south-east coast of Sardinia.[30][31] Later, Emerald assisted in the capture of Junon, Alceste, Courageuse, Salamine and Alerte in the action of 18 June 1799.[1][31] The British fleet under George Elphinstone was some 69 miles off Cape Sicié when three French frigates and two brigs were spotted. Elphinstone engaged them with three seventy-fours, Centaur, Bellona and Captain, and two frigates, Emerald and Santa Teresa.[32] The next evening, after a 28-hour chase, the French ships were forced into an action. The French squadron had scattered, enabling the British to attack it piecemeal. Bellona fired the first shots at 19:00 as she, Captain, and the two frigates closed with Junon and Alceste, both of which struck their colours immediately. Bellona then joined Centaur in chasing Courageuse. Faced with overwhelming odds, Courageuse also surrendered. Emerald then overhauled Salamine, and Captain took Alerte at around 23:30.[31][33]

Action on 7 April 1800

.jpg)

Emerald returned to blockade duty at Cádiz in April 1800, joining a squadron under Rear-Admiral John Thomas Duckworth that included the 74-gun ships Leviathan and Swiftsure, and the fire ship Incendiary. The squadron sighted a Spanish convoy on 5 April, which comprised 13 merchant vessels and three accompanying frigates, and at once gave chase.[34] At 03:00 the following day, Emerald managed to overhaul and cross the bow of a 10-gun merchantman, which, having nowhere to go, immediately surrendered.[35] By daybreak, the remainder of the Spanish convoy had scattered and the only ship visible was a 14-gun brig, Los Anglese. The absence of wind prevented the becalmed British vessels approaching her. Instead, Leviathan and Emerald lowered boats that rowed towards the brig, which they captured after a short exchange of fire.[34][35]

Other sails were now spotted in the east, west and south, forcing the British to divide their force: Swiftsure went south, Emerald east, and Leviathan west.[34] At midday, Emerald signalled that there were six vessels to the north-east, and Leviathan wore round to pursue. By dusk, the two British ships had nine Spanish craft in sight. Three ships were seen at midnight to the north-north-west, and by 02:00 the following morning, two had been identified as the enemy frigates Carmen and Florentina.[36] Duckworth ordered Emerald to take a parallel course to the enemy frigates in anticipation of a dawn attack, and at first light, the British closed with their opponents.[37]

The Spaniards had assumed the approaching vessels were part of their convoy, but by daybreak they had realised their error and vainly set more sail to escape. Being close enough to hail the Spanish crews, Duckworth ordered them to surrender. When the Spaniards ignored the demand, he ordered Leviathan and Emerald to open fire on the rigging of the Spanish vessels in order to disable them. Both Spanish frigates quickly surrendered.[37] Carmen had had 11 men killed and 16 wounded; Florentina 12 killed and 10 wounded, including her first and second captains. The two Spanish frigates were each carrying 1,500 quintals of mercury.[38]

A third frigate was visible on the horizon. Emerald immediately set off in pursuit but Duckworth recalled her and instead ordered her to locate the merchant ships; she secured four of the largest vessels by nightfall. The need to make the two captured frigates ready to sail delayed Leviathan, and by the time this was completed the third frigate had made her escape.[37] Leviathan then returned to rendezvous with Emerald, managing to take a further enemy brig before night fell. The following day, both British vessels sailed for Gibraltar with their prizes. On arrival, they encountered Incendiary, which had made port the previous day with two captured vessels of its own.[39] The small British squadron managed to secure nine merchant vessels and two frigates in total.[38][39]

Caribbean

Britain declared war on France in May 1803 following the short-lived Peace of Amiens and by June, Emerald, under the command of Captain James O'Bryen, had joined Samuel Hood's squadron in the Leeward Islands. Prior to the British invasion of St Lucia on 21 June, she harassed enemy shipping, disrupting the island's resupply.[40]

The invasion force left Barbados on 20 June. It comprised Hood's 74-gun flagship Centaur, the 74-gun Courageux, the frigates Argo and Chichester, and the sloops Hornet and Cyane. The following morning, Emerald and the 18-gun sloop Osprey had joined them. By 11:00, the squadron was anchored in Choc Bay.[40][41] The troops were landed by 17:00 and half an hour later the town of Castries was in British hands.[42] In the island's main fortress, Morne-Fortunée, the French troops refused to surrender; the British stormed it at 04:00 on 22 June, and by 04:30 St Lucia was in British hands. Following this easy victory, the British sent a force to Tobago, which capitulated on 1 July.[42]

Emerald was between St Lucia and Martinique on 24 June, when she captured the 16-gun French privateer Enfant Prodigue after a 72-hour chase. The French vessel was under the command of lieutenant de vaisseau Victor Lefbru and was carrying dispatches for Martinique.[40] The Royal Navy took Enfant Prodigue into service as HMS St Lucia.[43]

While in the company of the 22-gun brig HMS Heureux, Emerald intercepted and captured a Dutch merchant vessel travelling between Surinam and Amsterdam on 10 August.[44] On 5 September, she captured two French schooners,[45] and later that month took part in attacks on Berbice, Essequibo and Demarara.[46]

Fort Diamond

Emerald's first lieutenant, Thomas Forest, commanded the 6-gun cutter Fort Diamond on 13 March 1804 when, with 30 of Emerald's crew aboard, she captured a French privateer off Saint-Pierre, Martinique.[47] Contrary winds prevented the privateer, Mosambique, from entering St Pierre and she had sought shelter beneath the batteries at Seron.[48] Because Emerald was too far downwind, Captain O'Bryen used boats and crew from Emerald to create a diversion and draw fire from the battery while Fort Diamond approached from the opposite direction, rounded Pearl Rock (some two miles off the coast), and bore down on Mosambique.[47][48] Forest put the cutter alongside with such force that a chain securing the privateer to the shore snapped. The 60-man French crew abandoned their vessel and swam ashore.[48] The Royal Navy took Mosambique into service.[49]

Capture of Surinam

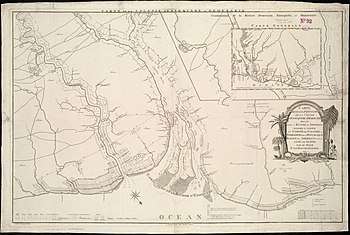

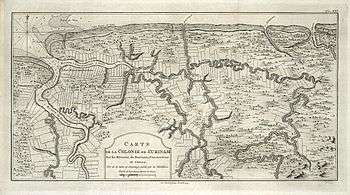

In the spring of 1804, Emerald and her crew took part in an invasion of Surinam. The invasion force consisted of Hood's flagship Centaur, Emerald, the 44-gun heavy frigates Pandour and Serapis, the 28-gun sixth-rate Alligator, the 12-gun schooner Unique, the 12-gun corvette Hippomenes, and the 8-gun Drake, together with 2,000 troops under Brigadier-General Sir Charles Green. The force arrived from Barbados on 25 April after a twenty-two-day journey.[50][51] The sloop Hippomenes, a transport and a further three armed vessels, landed Brigadier-General Frederick Maitland and 700 troops at Warapee Creek on the night of 30 April. The following night, O'Bryen was ordered to assist Brigadier-General Hughes in the taking of Braam's Point. A sandbar initially prevented Emerald from entering the Surinam River but O'Bryen forced her across on the rising tide, with Pandour and Drake following. Anchoring close by, the three British ships quickly put the Dutch battery of 18-pounders out of action and captured the fort without loss of life.[50][52]

Emerald, Pandour, and Drake then pushed up the river, sometimes in less water than the frigates required to float properly, until on 5 May they arrived close to the forts Leyden and Frederici. The British landed a detachment of troops under Hughes some distance away, which marching under the cover of the forests and swamps, launched an attack that resulted in the swift capture of the two forts.[53] By this time, most of the squadron had managed to work its way up the river as far as Frederici, Maitland was advancing along the Commewine River, and with troops poised to attack the fort of New Amsterdam, the Batavian commandant, Lieutenant-Colonel Batenburg, duly surrendered.[54]

Emerald captured the vessel Augusta, which was under American colours, on 22 August and sent her into Antigua with the cargo of wine that she had been carrying from Leghorn to Guadeloupe.[55] Emerald left Tortola on 26 October as escort to a convoy of 50 vessels for England but having parted from them in a storm, she put into Madeira in distress on 11 December.[56][57]

Service on the Home Station

Between February and June 1806, Emerald underwent repairs at Deptford dockyard and was recommissioned under Captain John Armour; Frederick Lewis Maitland assumed command in the first quarter of 1807.[1] While in the Basque Roads in April, Emerald captured the 14-gun privateer Austerlitz, a brig from Nantes under the command of Captain Gatien Lafont.[58] Emerald, while escorting a Spanish polacca that she had taken, spotted and captured the privateer on 14 April after a ten-hour chase.[1][59] Austerlitz had been out of port two days but had made no captures; the polacca was the Spanish ship Prince of Asturias, which had sailed from La Guayra with a cargo of cocoa, bark and indigo. Emerald sent both prizes into Plymouth, where they arrived on 22 April. Emerald herself set off in pursuit of another vessel from La Guayra.[60][Note 8]

Emerald recaptured Zulema which had been plundered and taken by a French privateer as she sailed from Philadelphia to Liverpool. She arrived in Plymouth under her master, Mr Howard, on 4 May.[62] During December, Plymouth received more of Emerald's captures. At the beginning of the month, Young Elias was detained. Her master Monsieur Delance, had been sailing from Philadelphia to Bordeaux.[63] On 26 December, Mr Seaton's vessel, Friendship was caught returning from France.[64]

Apropos

Emerald's boats participated in a cutting-out expedition in Viveiro harbour on 13 March 1808. While cruising inshore at around 17:00, Emerald spotted a large French schooner, Apropos,[Note 9] of 250 tons (bm), anchored in the bay. Apropos was armed with twelve 8-pounder guns, though pierced for 16, and had a crew of more than 70 men under the command of lieutenant de vaisseau Lagary.[65]

The crews of the schooner and of the two batteries guarding the harbour had seen Emerald but Maitland still made plans to attack Apropos.[1][66] He soon discovered it was not possible to place Emerald so as to engage both enemy batteries simultaneously, and instead sent landing parties to silence the guns, which had been firing on his ship since 17:30.[66] The first landing party, led by Lieutenant Bertram and accompanied by two marine lieutenants and two master mates, stormed the outer fort. Maitland then positioned Emerald close to the second battery while a boat under the command of his third lieutenant, Smith, landed about a mile along the shore. This second landing party encountered Spanish soldiers, but drove them off and pursued them inland. By the time Smith's party returned to the beach, Emerald had already silenced the battery. In the darkness, Smith subsequently failed to locate the fort.[66]

The crew of Apropos had run her ashore soon after Emerald had entered the harbour. The harbour batteries having been destroyed, Captain Maitland sent a further force under Midshipman Baird to secure and refloat the French ship. The original landing party under Lieutenant Bertram, which had already encountered and dispersed 60 members of the schooner's crew, met Baird's party on the beach. The British made several unsuccessful attempts to re-float the schooner before being forced to set her afire and depart.[66] British casualties were heavy. Emerald had nine men killed, and 16 wounded, including Lieutenant Bertram. Maitland estimated that French casualties too had been heavy.[65]

In 1847 the Admiralty issued the clasp "Emerald 13 March 1808" to the Naval General Service Medal to the ten surviving claimants from the action.[67]

Back in the Basque Roads

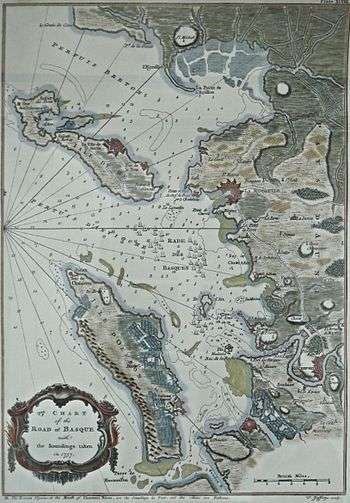

A French schooner Amadea arrived in Plymouth on 15 December 1808 having previously been captured and sent in by Emerald.[68] Back in the Basque Roads on 23 February 1809, Emerald was this time part of a squadron under Robert Stopford. Stopford's flagship, the 80-gun Caesar, was also accompanied by the seventy-fours Defiance and Donegal, and the 36-gun frigates Amethyst and Naiad.[69] At 20:00, Stopford's squadron was anchored off the Chassiron Lighthouse, to the north-west of Ile d'Oléron, when the sighting of several rockets prompted him to investigate. About an hour later, sails were seen to the east which the British followed until daylight the following morning. The sails belonged to a French squadron that Stopford deduced to be out of Brest and which heaved to in the Pertuis d'Antioche.[69]

The French force comprised eight ships of the line and two frigates, and Stopford immediately sent Naiad to apprise Admiral James Gambier of the situation. Naiad had not gone too far however when she signalled that there were three other vessels to the north-west. Stopford ordered Amethyst and Emerald to remain while he and the rest of the squadron set off in pursuit. The British frigate Amelia and the sloop Doterel also joined the chase.[69] Caesar, Donegal, Defiance, and Amelia eventually drove the three French frigates ashore and destroyed them.[69][70]

Emerald and Amethyst had more success in the spring of 1809 when on 23 March they captured the brigs Caroline and Serpent. In April, Emerald assisted Amethyst in the chase of a large 44-gun frigate off Ushant.[71][72] Emerald sighted Niemen, with a main battery of 18-pounders and under the command of Captain Dupoter, at 11:00 on 5 April and immediately signalled Amethyst for assistance. Amethyst caught a glimpse of the French forty-four just as she turned away to the south-east and gave chase but by 19:20 had lost sight of both Niemen and Emerald. Amethyst fell in with Niemen again at around 21:30 and engaged her. Niemen was forced to strike when a second British frigate, Arethusa came into view and fired a broadside.[72] The Royal Navy took Niemen into service under her existing name.[73]

On 26 March, Enfant de Patria arrived at Plymouth. Patria, of 500 tons (bm), 10 guns, and 60 men, had sailed from France for Île de France when Emerald and Amethyst captured her.[74][Note 10] Two days later Emerald captured a second letter of marque, the 4-gun Aventurier, bound for the relief of Guadeloupe. She had a crew of 30 men.[65]

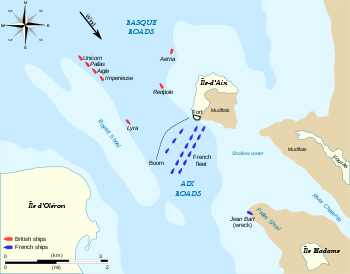

Battle of the Basque Roads

Emerald was part of the fleet under Admiral Lord Gambier that fought the Battle of the Basque Roads in April 1809.[75] The French ships were anchored under the protection of the powerful batteries on the Isle d'Aix[76] when on 11 April Lord Cochrane attacked them with fireships and explosive vessels.[77] Emerald provided a diversion to the east of the island with the brigs Beagle, Doterel, Conflict, and Growler.[77] The fireships met with only partial success; the French, having anticipated such an attack, had rigged a boom across the channel.[78] One of the explosive vessels breached the boom, leading the French to cut their cables and drift on to the shoals.[79]

The following day, after much delay, Gambier ordered a battle squadron to reinforce Cochrane in the Basque Roads. The British ships anchored, with springs, in a crescent around some of the stranded French ships, and exchanged fire.[Note 11] Emerald took up position ahead of Indefatigable and behind Aigle and Unicorn, and directed her fire mainly towards the French ships of the line, Varsovie and Aquilon, both of which struck at around 17:30.[81]

At 20:00, Emerald, along with the other British frigates and brigs, weighed and anchored with the 74-gun HMS Revenge in the Maumusson passage to the south of Oléron while a second fireship attack was under preparation.[82] Although the fireships were ready in the early hours on the 13th, contrary winds prevented their deployment. The British instead set Varsovie and Aquilon alight just after 03:00, on the orders of Captain John Bligh, after removing their crews.[83] Emerald, and the other vessels moored with her, were recalled at 05:00 but owing to the lack of water, only the brigs were able to pass further up the river.[84] Emerald therefore took no further part in the attack, which continued until 29 April when the last French ship was able to free herself from the mud and escape up the river to Rochefort.[85]

Later service

Emerald took two French sloops in July 1809.[86] Deux Freres, en route for Guadeloupe from Rochelle when captured, arrived in Plymouth on 26 July.[87] A week later, Emerald captured the French schooner Balance, which had been sailing to France from Guadeloupe.[88] Both captures carried letters of marque, a government licence authorising the attack and capture of enemy vessels. The first, of four guns, was carrying a small reinforcement for Guadeloupe's garrison. The second, also of four guns, was carrying a cargo of coffee and other colonial produce.[65]

While off the coast of Ireland on 8 October, Emerald rescued a British brig by capturing Incomparable, an 8-gun French privateer. The Frenchman was about to take the British vessel when Emerald intervened.[89] Incomparable had a crew of 63 men and was four days out of Saint-Malo, but had not yet captured any other vessel.[65][Note 12] Still in Irish waters on 6 November, Emerald took the 16-gun French brig Fanfaron, two days out of Brest and bound for Guadeloupe.[92] After an all-night chase, Emerald caught up. Capitaine de fregate Croquet Deschateurs of Fanfaron resisted, firing several broadsides and a final double-shotted broadside. Unable to escape, Deschateurs prepared to board but Emerald evaded the manoeuvre and fired a broadside that dismasted Fanfaron, leaving Deschateurs no option but to surrender his vessel. The subsequent French court-martial not only absolved Deschateurs of any liability for the loss but also commended him for his conduct.[93] Four days later Emerald arrived at Cork with Fanfaron and Luna. Fanfaron, with a crew of 113, had been carrying a cargo of flour, salt and other provisions, as well as iron, lead and nails, all for Guadeloupe.[94][Note 13]

At the beginning of February 1810, Emerald captured and sent into Plymouth, Commerce, Hanson, master, which had been sailing from Drontheim to Bordeaux.[96] Then on 22 March, Emerald captured the 350-ton (bm) Belle Etoile in the Bay of Biscay. Caught after a twelve-hour chase during which she jettisoned much of her cargo; Belle Etoile, out of Bayonne, was pierced for 20 guns but only carried eight.[97] Carrying a cargo of wine, flour, oil, and other merchandise to Île de France,[65] she was sent into Cork with her 56-man crew.[98] Emerald captured an American ship, Wasp, in July 1810.[99] Wasp was carrying 91 passengers from New York to Bordeaux; they arrived at Plymouth on 30 July.[100]

Emerald was still serving on the Home Station on 11 April 1811 when she sent into Cork a French privateer.[101] This was the 18-gun Auguste (or Augusta), which had been taken on 6 April.[99] Nearly a month later, on 5 July, Emerald left Madeira in the company of five East Indiamen[Note 14] and was still on convoy duties later that month when a transport ship spotted her escorting thirteen vessels off the coast of West Africa on 18 July.[Note 15][102][103]

Fate

In November 1811, Emerald sailed to Portsmouth and was laid up in ordinary. Fitted out as a receiving ship in 1822, she was eventually broken up in January 1836.[1]

See also

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

- The original Amazon-class frigates were 32-gun, 12-pounder, frigates of 677 tons (bm), designed by Sir John Williams and built between 1771 and 1782.[2] In need of a larger frigate, in 1794, the Admiralty asked Sir William Rule to design a 36-gun, 18-pounder, Amazon-class frigate. Originally a series of four, by the time the first one had been launched in 1795, Rule had already drawn up plans for Naiad; an expanded version which was larger at 1,013 tons (bm), had a complement of 284 men and carried 38 guns.[1] A third design was unveiled in 1796, also with 38 guns but larger still at 1,038 tons (bm) and with a crew of 300 men. Two were ordered, one in April 1796 and a second in February 1797.[3]

- The second pair of Amazons were named Trent and Glenmore and were launched in 1796 on 24 February and 24 March, respectively.[1]

- Berkeley's reluctance to attack infuriated some of his fellow officers who asked for a court-martial. Minerve's captain, George Cockburn, however came down on Berkeley's side, opining to Jervis that, under a jury rig, Santisima Trinidad was still capable of making a defence.[6]

- In addition to Emerald and Vanguard, the squadron comprised Terpsichore, Bonne-Citoyenne and the 74-gun Orion. It left Gibraltar on 9 May 1798.[19]

- Anemone was the tartane Cincinnatus, which the French Navy had commissioned in June 1794 as an aviso, and renamed in May 1795. Her armament consisted of two 6-pounder and two 4-pounder guns, and four swivel guns.[24] which had left Toulon on 27 July and Malta on 26 August.[25]

- The Arabs captured some 17 to 20 survivors (accounts differ), and offered them to General Kleber, who ransomed them.[27]

- Adjutant General Jean-Baptiste Camin (1760–1798), came from Calais. After his death, the French erected a small fort on the outskirts of Cairo and named it in his honour.[29]

- Prince of Asturias was sold as a prize with the buyer being "McCarthy". Subsequently, Lloyd's Register for 1806 gives her burthen as 239 tons, her master's name as R. Harvey, and her home port as London.[61]

- Sometimes referred to as Apropus.

- Marshall describes Enfant de Patria as a letter of marque of 640 tons (bm), armed with eight guns, and carrying a crew of 60 men.[65]

- A spring was a second rope attached to the anchor cable so that by pulling on it, the ship could be slewed round contrary to wind and tide, which would otherwise determine the angle of the vessel.[80]

- The report in Lloyd's List describes Incomparable as being armed with 14 guns.[90] French records show that she was commissioned in November 1807. She served under René Rosse until March 1808, Jean-Baptiste Dupuis from December, and from May 1809 made two cruises under Charles Tribalau.[91] A third account gives her armament as eight 6-pounder guns and her crew as numbering 60 men.[65]

- The report in Lloyd's List describes Fanfaron as being armed with 18 guns and having a crew of 135 men. Luna, of and from New York, Southwark, master, had been carrying cotton and rice for San Sebastián when Emerald detained her.[95]

- The Indiamen were Minerva, Harleston, William Pitt, Lord Forbes, and Lady Lushington, all of which had arrived in Madeira three days earlier.[102]

- The transport ship, Fanny was travelling from Rio de Janeiro to Portsmouth, and on her arrival reported Emerald and her convoy, "all well" at 13°2′N 24°0′W.[103]

Citations

- Winfield p. 148

- Winfield pp. 193–196

- Winfield pp. 150–151

- Willis pp. 89–90

- James (Vol. II) p. 49

- Ralfe, James (1828). Volume 3 of The Naval Biography of Great Britain: Consisting of Historical Memoirs of Those Officers of the British Navy who Distinguished Themselves During the Reign of His Majesty George III. London: Whitmore & Fenn. p. 266. OCLC 561188819.

- Dull pp. 147–148

- Woodman p. 99

- Clowes (Vol. IV) p. 507

- James (Vol. II) p. 82

- "No. 14010". The London Gazette. 16 May 1797. p. 446.

- James (Vol. II) p. 83

- "No. 14032". The London Gazette. 29 July 1797. p. 717.

- James (Vol. II) pp. 53–54

- James (Vol. II) p. 54

- Heathcote p. 181

- Heathcote p. 182

- "No. 14041". The London Gazette. 2 September 1797. p. 835.

- James (Vol. II) p. 148

- James (Vol. II) p. 154

- Willis p. 168

- James (Vol. II) p. 183

- Clowes (Vol. IV) p. 373

- Winfield and Roberts (2015), p. 296.

- "No. 15082". The London Gazette. 20 November 1798. p. 1110.

- James (Vol. II) pp. 192–193

- Strathern (2009), pp. 223–225.

- Fonds Marine, p. 210.

- Le Fort Camin du Caire et l'Adjudant Général Camin (1760–1798), de Calais (1993).

- "No. 15162". The London Gazette. 23 July 1799. p. 740.

- "No. 15162". The London Gazette. 23 July 1799. p. 741.

- James (Vol. II) p. 262

- Troude (1867), Vol. III, p. 164.

- James (Vol. III) p. 37

- "No. 15253". The London Gazette. 29 April 1800. p. 421.

- James (Vol. III) pp. 37–38

- James (Vol. III) p. 38

- "No. 15253". The London Gazette. 29 April 1800. p. 423.

- "No. 15253". The London Gazette. 29 April 1800. p. 422.

- "No. 15605". The London Gazette. 26 July 1803. pp. 918–919.

- Clowes (Vol. V) p. 56

- James (Vol. III) p. 207

- Winfield p. 348

- "No. 15669". The London Gazette. 24 January 1804. p. 109.

- "No. 15669". The London Gazette. 24 January 1804. p. 110.

- "No. 16505". The London Gazette. 16 July 1811. p. 1329.

- "No. 15697". The London Gazette. 28 April 1804. p. 539.

- James (Vol. III) p. 253

- Winfield p. 364

- "No. 15712". The London Gazette. 19 June 1804. pp. 761–762.

- James (Vol III) pp. 288–289

- James (Vol. III) p. 289

- James (Vol. III) pp. 289–290

- James (Vol. III) p. 290

- Lloyd's List n° 4506. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List n° 4513. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List n° 4185. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Demerliac (2004), n° 2190, p. 278.

- "No. 16023". The London Gazette. 25 April 1807. p. 533.

- Lloyd's List, n°4146 – accessed 11 November 2015.

- "Lloyd's register of shipping. 1806. – Full View – HathiTrust Digital Library – HathiTrust Digital Library". HathiTrust. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4150. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4210. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List n°4215, – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Marshall (1824), Vol. II, Part 1, pp. 395–396.

- "No. 16130". The London Gazette. 22 March 1808. p. 416.

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. pp. 236–247.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4302. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- "No. 16234". The London Gazette. 4 March 1809. p. 289.

- "No. 16337". The London Gazette. 27 January 1810. p. 139.

- "No. 16303". The London Gazette. 3 October 1809. p. 1593.

- "No. 16246". The London Gazette. 11 April 1809. p. 499.

- Winfield p. 178

- Lloyd's List, n° 4340. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- "No. 17458". The London Gazette. 9 March 1819. p. 450.

- James (Vol. V) pp. 103–104

- James (Vol. V) p. 105

- James (Vol. V) p. 104

- James (Vol. V) pp. 108–109

- Davies p. 188

- James (Vol. V) p. 114.

- James (Vol. V) pp. 116–117

- James (Vol. V) p. 117.

- James (Vol. V) pp. 118–119.

- James (Vol. V) p. 122.

- "No. 16352". The London Gazette. 17 March 1810. p. 411.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4375. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4376. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- "No. 16310". The London Gazette. 28 October 1809. p. 1708.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4400. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Demerliac (2004), n° 2057, p. 267.

- "No. 16315". The London Gazette. 14 November 1809. p. 1826.

- Troude (1867), Vol. IV, pp. 74–77.

- European Magazine and London Review, Vol. 56, p. 469.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4408. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4432. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- "No. 16357". The London Gazette. 31 March 1810. p. 489.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4446. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- "No. 16548". The London Gazette. 3 December 1811. p. 2341.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4481. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List, n° 4554. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List, №4593. – accessed 12 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List, №4594. – accessed 12 July 2016.

References

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Davies, David (1996). Fighting Ships. Fulham Palace Road, London.: Constable and Robinson Limited. ISBN 1-84119-469-7.

- Demerliac, Alain (2004). La Marine du Consulat et du Premier Empire: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1800 A 1815 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-903179-30-1.

- Dull, Jonathan R. (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-549-4.

- Fonds Marine. Campagnes (opérations; divisions et stations navales; missions diverses). Inventaire de la sous-série Marine BB4. Tome premier : BB4 1 à 209 (1790–1804)

- Heathcote, Tony (2005). Nelson's Trafalgar Captains and Their Battles. Leo Cooper Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84415-182-0.

- Henderson, James (2011). Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84884-526-8.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume II, 1797–1799. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume III, 1800–1805. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume V, 1808–1811. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Strathern, Paul (2009) Napoleon in Egypt. (Bantam Books Trade Paperbacks). ISBN 978-0-553-38524-3

- Marshall, John (1823–1835) Royal naval biography, or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired-captains, post-captains, and commanders, whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of sea officers at the commencement of the present year 1823, or who have since been promoted ... (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown).

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France, Volume III (in French). Challamel ainé.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France, Volume IV (in French). Challamel ainé.

- Willis, Sam (2013). In the Hour of Victory – The Royal Navy at War in the Age of Nelson. London: Atlantic Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85789-570-7.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

- Winfield, Rif & Stephen S Roberts (2015) French Warships in the Age of Sail 1786–1861: Design Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-204-2

- Woodman, Richard (2014) [2001]. The Sea Warriors – Fighting Captains and Frigate Warfare in the Age of Nelson. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-202-8.

External links