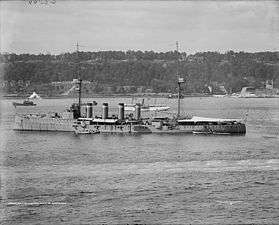

HMS Duke of Edinburgh

HMS Duke of Edinburgh was the lead ship of the Duke of Edinburgh-class armoured cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the early 1900s. She was stationed in the Mediterranean when the First World War began and participated in the pursuit of the German battlecruiser SMS Goeben and light cruiser SMS Breslau. After the German ships reached Ottoman waters, the ship was sent to the Red Sea in mid-August to protect troop convoys arriving from India. Duke of Edinburgh was transferred to the Grand Fleet in December 1914 and participated in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. She was not damaged during the battle and was the only ship of her squadron to survive. She was eventually transferred to the Atlantic Ocean in August 1917 for convoy escort duties.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Duke of Edinburgh |

| Namesake: | Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Edinburgh |

| Ordered: | 1902/1903 Naval programme |

| Builder: | Pembroke dockyard |

| Laid down: | 11 February 1903 |

| Launched: | 14 June 1904 |

| Completed: | 20 January 1906 |

| Stricken: | 1919 |

| Fate: | sold 12 April 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Duke of Edinburgh-class armoured cruiser |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 505 ft 6 in (154.1 m) |

| Beam: | 73 ft 6 in (22.4 m) |

| Draught: | 27 ft (8.2 m) (maximum) |

| Installed power: | 23,000 ihp (17,000 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Range: | 8,130 nmi (15,060 km; 9,360 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 789 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

The ship was sold for scrap in 1920.

Description

Duke of Edinburgh displaced 12,590 long tons (12,790 t) as built and 13,965 long tons (14,189 t) fully loaded. The ship had an overall length of 505 feet 6 inches (154.1 m), a beam of 73 feet 6 inches (22.4 m) and a draught of 27 feet (8.2 m). She was powered by four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, driving two shafts, which produced a total of 23,000 indicated horsepower (17,150 kW) and gave a maximum speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph). The engines were powered by 20 Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers and six cylindrical boilers. The ship carried a maximum of 2,150 long tons (2,180 t) of coal and an additional 600 long tons (610 t) of fuel oil that was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. At full capacity, she could steam for 8,130 nautical miles (15,060 km; 9,360 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). The ship's complement was 789 officers and enlisted men.[1]

Armament

Her main armament consisted of six BL 9.2-inch (234 mm) Mark X guns in single turrets. The guns were distributed in two centerline turrets (one each fore and one aft) and four turrets disposed in the corners about the funnels. Her secondary armament of ten BL 6-inch Mk XI guns was arranged in single casemates. They were mounted amidships on the main deck and were only usable in calm weather. Twenty Vickers quick-firing (QF) three-pounders were fitted, six on turret roofs and fourteen in the superstructure. The ship also mounted three submerged 17.72-inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes.[2]

History

Duke of Edinburgh was ordered under the 1902/1903 naval construction programme as the lead ship of her class. She was laid down on 11 February 1903 at Pembroke Royal Dockyard in Wales. She was launched on 14 June 1904 and completed on 20 January 1906[3] at a cost of £1,193,414.[1] Duke of Edinburgh was named after Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, one of Queen Victoria's sons.[4]

The ship was assigned to the 5th Cruiser Squadron from 1906 to 1908 and was then transferred to the 1st Cruiser Squadron of the Channel Fleet. When the Royal Navy's cruiser squadrons were reorganized in 1909, Duke of Edinburgh rejoined the 5th Cruiser Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet.[5] On 13 August 1910 Duke of Edinburgh ran aground on Atherfield Ledge, Isle of Wight. She was successfully refloated, but in the resulting Court-martial to investigate the incident, the ship's Captain and Navigating Officer were severely reprimanded and the latter dismissed from the ship.[6] She helped to rescue the survivors of the SS Delhi which ran aground off the coast of Morocco in December 1911.[7] From 1913 to 1914 she served with the 1st Cruiser Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet.[5]

When the British began to prepare for war in July 1914, the ship was refitting at Malta. Her refit was cut short and she joined the rest of her squadron in the southern approaches to the Adriatic.[8] She was involved in the pursuit of the German battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau at the outbreak of World War I, but was ordered not to engage them.[9] On 10 August Duke of Edinburgh and her sister ship HMS Black Prince were ordered to the Red Sea to protect troop convoys arriving from India. While on that duty the ship captured the German merchantman Altair of 3,200 tons GRT on 15 August.[10] While escorting a troop convoy from India to France in November 1914, Duke of Edinburgh provided cover to three battalions of infantry that seized the Turkish fort at Cheikh Saïd at the entrance to the Red Sea. The ship then landed a demolition party, which blew the fort up on 10 November; she then rejoined the convoy.[11]

Duke of Edinburgh rejoined the 1st Cruiser Squadron, which had been transferred to the Grand Fleet in the meantime, in December 1914. In March 1916 the ship had her main deck 6-inch guns removed and the openings plated over. Six of the guns were remounted on the upper deck, three on each side, between the wing turrets, protected by gun shields.[9] At the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916, the 1st Cruiser Squadron was in front of the Grand Fleet, on the right side. At 5:47 p.m.[Note 1] The two leading ships of the squadron, the flagship, HMS Defence, and HMS Warrior, spotted the German II Scouting Group and opened fire. Their shells felt short and the two ships turned to port in pursuit, cutting in front of the battlecruiser HMS Lion, which was forced to turn away to avoid a collision. Duke of Edinburgh could not follow the first two ships and turned to port (northeast).[12] The ship spotted the disabled German light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden at 6:08 and fired twenty rounds at her. By about 6:30 she had steamed to a position off the starboard bow of HMS King George V, the leading ship of the 2nd Battle Squadron, where her funnel smoke obscured the German ships from the foremost dreadnoughts of the 2nd Battle Squadron.[13] A torpedo attack by German destroyers on Admiral Beatty's battlecruisers, failed, but forced Duke of Edinburgh to evade one torpedo at 6:47. The ship reported a submarine sighting at 7:01, although no German submarines were operating in the area. She fired at another false submarine contact between 7:45 and 8:15.[14]

After the battle, Duke of Edinburgh was attached to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron and remained at sea until 2 June, searching for disabled ships. She arrived in Scapa Flow on the afternoon of 3 June.[15] On the evening of 18 August 1916, the Grand Fleet, including Duke of Edinburgh, put to sea in response to a deciphered message that the High Seas Fleet, minus the II Battle Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The Germans planned to bombard the port of Sunderland on 19 August, with extensive reconnaissance provided by airships and submarines. The Germans broke off their planned attack to pursue a lone British battle squadron reported by an airship, which was in fact the Harwich Force under Commodore Tyrwhitt. Realising their mistake, the Germans then set course for home. After Jutland the 2nd Cruiser Squadron, now including Duke of Edinburgh, was ordered to reinforce the patrols north of the Shetland Islands against German blockade runners and commerce raiders.[16] The ship's foremast was converted to a tripod to support the weight of a fire-control director in May 1917, but when the director was actually fitted is not known. Two more 6-inch guns were added in embrasures on the forecastle deck during that same refit.[9] She was transferred to the North America and West Indies Station in August 1917 for convoy escort duties,[17] where she remained for the duration of the war. Upon her return, Duke of Edinburgh was stationed in the Humber,[9] before she was sold for scrap on 12 April 1920 and broken up at Blyth in Northumberland.[4]

Notes

Footnotes

- Parkes, p. 442

- Parkes, pp. 442–43

- Chesneau and Kolesnik, p. 72

- Silverstone, p. 228

- Parkes, p. 444

- "Naval Matters—Past and Prospective: Portsmouth Dockyard". The Marine Engineer and Naval Architect. Vol. 33. October 1910. p. 98.

- "Three Princesses Nearly Drowned" (PDF). New York Times. 14 December 1911. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- Corbett, I, pp. 33, 35

- Gardiner and Gray, p. 13

- Corbett, I, pp. 83, 87–88

- Corbett, I, pp. 377–79

- Marder, pp. 97–98

- Campbell, pp. 122, 150, 152

- Campbell, pp. 161, 164, 250

- Newbolt, IV, p. 1

- Newbolt, IV, pp. 36, 192

- Newbolt, V, p. 135

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55821-759-2.

- Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Corbett, Julian. Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. I (2nd, reprint of the 1938 ed.). London and Nashville, TN: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-256-X.

- Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. II (reprint of the 1929 second ed.). London and Nashville, TN: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-74-7.

- Eger, Christopher L. (2012). "Hudson-Fulton Naval Celebration, Part I". Warship International. XLIX (2): 123–151. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1978). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919. III: Jutland and After, May 1916 – December 1916 (Second ed.). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215841-4.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. IV (reprint of the 1928 ed.). Nashville, TN: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-253-5.

- Newbolt, Henry. Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. V (reprint of the 1931 ed.). London and Nashville, TN: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-72-0.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Duke of Edinburgh (ship, 1904). |