Gwanggaeto the Great

Gwanggaeto the Great (374–413, r. 391–413)[1] was the nineteenth monarch of Goguryeo. His full posthumous name means "Entombed in Gukgangsang, Broad Expander of Domain,[1] Peacemaker,[2] Supreme King", sometimes abbreviated to Hotaewang.[2] His era name is Yeongnak and he is occasionally recorded as Yeongnak Taewang ("Supreme King" or "Emperor" Yeongnak). Gwanggaeto's imperial reign title meant that Goguryeo was on equal standing as an empire with the imperial dynasties in China.[1][3][4]

| Emperor Gwanggaeto the Great | |

| Hangul | 광개토태왕 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 廣開土太王 |

| Revised Romanization | Gwanggaeto-taewang |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kwanggaet'o-taewang |

| IPA | [kwaŋ.ɡɛ.tʰo.dɛ.waŋ] |

| Birth name | |

| Hangul | 고담덕 |

| Hanja | 高談德 |

| Revised Romanization | Go Damdeok |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ko Tamdǒk |

| IPA | [ko.dam.dʌk̚] |

| Posthumous name | |

| Hangul | 국강상광개토경평안호태왕 |

| Hanja | 國岡上廣開土境平安好太王 |

| Revised Romanization | Gukgangsang-gwanggaetogyeong-pyeongan-hotaewang |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kukkangsang-kwanggaet'ogyŏng-p'yŏngan-hot'aewang |

| IPA | [kuk̚.k͈aŋ.saŋ.ɡwaŋ.ɡɛ.tʰo.ɡjʌŋ.pʰjʌŋ.an.ɦo.tʰɛ.waŋ] |

| Monarchs of Korea |

| Goguryeo |

|---|

|

Under Gwanggaeto, Goguryeo began a golden age,[5][6][7] becoming a powerful empire and one of the great powers in East Asia.[8][9][10][11] Gwanggaeto made enormous advances and conquests into: Western Manchuria against Khitan tribes; Inner Mongolia and the Maritime Province of Russia against numerous nations and tribes;[12][13] and the Han River valley in central Korea to control over two-thirds of the Korean peninsula.[3][4]

In regard to the Korean peninsula, Gwanggaeto defeated Baekje, the then most powerful of the Three Kingdoms of Korea,[3] in 396, capturing the capital city of Wiryeseong in present-day Seoul.[14] In 399, Silla, the southeastern kingdom of Korea, sought aid from Goguryeo due to incursions by Baekje troops and their Wa allies from the Japanese archipelago.[4] Gwanggaeto dispatched 50,000 expeditionary troops,[15] crushing his enemies and securing Silla as a de facto protectorate;[4][16] he thus subdued the other Korean kingdoms and achieved a loose unification of the Korean peninsula under Goguryeo.[4][17][18] In his western campaigns, he defeated the Xianbei of the Later Yan empire and conquered the Liaodong peninsula,[3] regaining the ancient domain of Gojoseon.[4][19]

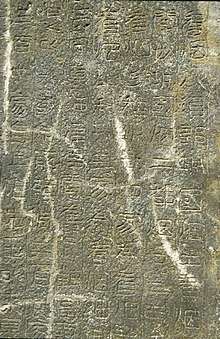

Gwanggaeto's accomplishments are recorded on the Gwanggaeto Stele, erected in 414 at the supposed site of his tomb in Ji'an along the present-day China–North Korea border.[20] Constructed by his son and successor Jangsu, the monument to Gwanggaeto the Great is the largest engraved stele in the world.[21][22]

Birth and background

At the time of Gwanggaeto's birth, Goguryeo was not as powerful as it once had been. In 371, three years prior to Gwanggaeto's birth, the rival Korean kingdom of Baekje, under the great leadership of Geunchogo, soundly defeated Goguryeo, slaying the monarch Gogukwon and sacking Pyongyang.[23][24] Baekje became one of the dominant powers in East Asia. Baekje's influence was not limited to the Korean peninsula, but extended across the sea to Liaoxi and Shandong in China, taking advantage of the weakened state of Former Qin, and Kyushu in the Japanese archipelago.[25] Goguryeo was inclined to avoid conflicts with its ominous neighbor,[26] while cultivating constructive relations with the Former Qin,[27] the Xianbei, and the Rouran, in order to defend itself from future invasions and to bide time to reshape its legal structure and to initiate military reforms.[28]

Gogukwon's successor, Sosurim, adopted a foreign policy of appeasement and reconciliation with Baekje,[26] and concentrated on domestic policies to spread Buddhism throughout Goguryeo's social and political systems.[29] Furthermore, due to the defeats that Goguryeo had suffered at the hands of the proto-Mongol Xianbei and Baekje, Sosurim instituted military reforms aimed at preventing such defeats in the future.[28] Sosurim's internal arrangements laid the groundwork for Gwanggaeto's expansion.[1]

Sosurim's successor, Gogukyang, invaded Later Yan, the successor state of Former Yan, in 385 and Baekje in 386.[30][31]

Reign

Rise to power and campaigns against Baekje

Gwanggaeto succeeded his father, Gogukyang, upon Gogukyang's death in 391. Upon Gwanggaeto's coronation, Gwanggaeto adopted the era name Yeongnak (Eternal Rejoicing) and the title Taewang (Supreme King), which was equivalent to "emperor",[32] affirming that he was an equal to the Imperial rulers of China.[1][3][4]

In 392, Gwanggaeto led an attack on Baekje with 40,000 troops, capturing 10 walled cities.[33] In response, Asin, the monarch of Baekje, launched a counterattack on Goguryeo in 393 but was defeated.[33] Despite the ongoing war, during 393, Gwanggaeto established 9 Buddhist temples in Pyongyang.[34][35] Asin invaded Goguryeo once more in 394, but was defeated again.[33] After suffering multiple defeats against Goguryeo, Baekje's political stability began to crumble.[18] In 395, Baekje was defeated once more by Goguryeo and was pushed south to its capital of Wiryeseong on the Han River.[33][36] In the following year, in 396, Gwanggaeto led an assault on Wiryeseong by land and sea, using the Han River, and triumphed over Baekje.[33] Gwanggaeto captured the Baekje capital and the defeated Asin submitted to him,[4][37] surrendering a prince and 10 government ministers.[33][38]

Northern conquests

In 395, while his campaign against Baekje was ongoing to the south, Gwanggaeto made an excursion to invade the Khitan Baili clan to the west on the Liao River,[39] destroying 3 tribes and 600 to 700 camps.[40] In 398, Gwanggaeto conquered the Sushen people to the northeast,[4] who were Tungusic ancestors of the Jurchens and Manchus.[41]

In 400, while Gwanggaeto was occupied with Baekje, Gaya, and Wa troops in Silla, the Xianbei state of Later Yan, founded by the Murong clan in present-day Liaoning, attacked Goguryeo.[42] Gwanggaeto repulsed the Xianbei troops.[19][43] In 402, Gwanggaeto retaliated and conquered the prominent fortress called 宿軍城 near the capital of Later Yan.[42][44] In 405 and again in 406, Later Yan troops attacked Goguryeo fortresses in Liaodong (遼東城 in 405, and 木底城 in 406), but was defeated both times.[42] Gwanggaeto conquered all of Liaodong.[1][4] By conquering Liaodong, Gwanggaeto recovered the ancient domain of Gojoseon;[4][19] Goguryeo controlled Liaodong until the mid-late 7th century.

In 407, Gwanggaeto dispatched 50,000 troops consisting of infantry and cavalry and won a great victory, completely annihilating the enemy troops and pillaging about 10,000 armors and countless war supplies; the opponent can be interpreted as Later Yan, Baekje, or Wa.[42][45]

In 410, Gwanggaeto attacked Eastern Buyeo to the northeast.[42]

Southern campaigns

In 400, Silla, another Korean kingdom in the southeast of the Korean peninsula, requested aid from Goguryeo in repelling an allied invasion by Baekje, Gaya, and Wa. Gwanggaeto dispatched 50,000 troops and annihilated the enemy coalition.[4] Thereupon, Gwanggaeto influenced Silla as a suzerain,[16] and Gaya declined and never recovered. In 402, Gwanggaeto returned Prince Silseong,[46] who had resided in Goguryeo as a political hostage since 392, back home to Silla and appointed him as the king of Silla.

In 404, Gwanggaeto defeated an attack by the Wa from the Japanese archipelago on the southern border of what was once the Daifang commandery, inflicting enormous casualties on the enemy.[42][47][48]

Death and legacy

Gwanggaeto died of an unknown illness in 413 at the age of 39. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Jangsu, who ruled Goguryeo for 79 years until the age of 98,[1] the longest reign in East Asian history.[49]

Gwanggaeto's conquests are said to mark the zenith of Korean history, building and consolidating a great empire in Northeast Asia and uniting the Three Kingdoms of Korea under his influence.[4][18] Gwanggaeto conquered 64 walled cities and 1,400 villages.[1][4] Except for the period of 200 years beginning with Jangsu, who would build upon his father's domain, and the golden age of Balhae, Korea never before or since ruled such a vast territory. There is archaeological evidence that Goguryeo's maximum extent lay even further west in present-day Mongolia, based on discoveries of Goguryeo fortress ruins in Mongolia.[50][51][52] Gwanggaeto established his own era name, Yeongnak Eternal Rejoicing, proclaiming Goguryeo monarchs equal to their counterparts in the Chinese mainland.[1][3][4]

Gwanggaeto the Great is one of two rulers of Korea whose names are appended with the title "the Great", with the other being Sejong the Great of Joseon, who created Hangul the Korean alphabet, to promote literacy among the common people,[53] and made great advances in science.[54][55]

Gwanggaeto is regarded by Koreans as one of the greatest heroes in Korean history, and is often taken as a potent symbol of Korean nationalism.

The Gwanggaeto Stele, a 6.39 meter tall monument erected by Jangsu in 414, was rediscovered in the late 19th century.[20] The stele was inscribed with information about Gwanggaeto's reign and achievements, but not all the characters and passages have been preserved. Korean and Japanese scholars disagree on the interpretation in regard to passages on the Wa.

The Republic of Korea Navy operates Gwanggaeto the Great-class destroyers, built by Daewoo Heavy Industries and named in honor of the monarch.

A prominent statue of Gwanggaeto alongside a replica of the Gwanggaeto Stele were erected in the main street of Guri city in Gyeonggi province.[56][57]

Depiction in arts and media

Film and television

- Portrayed by Yoo Seung-ho and Bae Yong-joon in the 2007 MBC TV series The Legend.

- Portrayed by Lee Tae-gon in the 2011-2012 KBS1 TV series Gwanggaeto, The Great Conqueror.[58]

- Portrayed by Lee Do Yeob in the 2017 KBS TV Chronicles of Korea.

Literature

Many novels, comics, and games about Gwanggaeto the Great have been released in Korea.[59][60][61]

Games

The popular[62] and award-winning[63] Korean mobile game Hero for Kakao features Gwanggaeto as a playable character.[64]

Age of Empires: World Domination, a mobile game produced in collaboration with series owner Microsoft,[65] includes Gwanggaeto as a selectable hero of the Korean civilization.[66]

Others

The International Taekwon-Do Federation created a pattern, or teul, to honor Gwanggaeto the Great. The pattern's diagram represents Gwanggaeto's territorial expansion and recovery of lost territories, and the 39 movements represent the first two numbers of 391 AD, the year when Gwanggaeto came to the throne.[67]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gwanggaeto the Great. |

- List of Korea-related topics

- History of Korea

- Three Kingdoms of Korea

- List of Korean monarchs

References

- Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 9780674615762. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- 한국의 세계문화유산 여행: 세계가 인정한 한국의 아름다움 (in Korean). 상상출판. 2011-10-19. p. 209. ISBN 9791186163146. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Kim, Djun Kil (2014-05-30). The History of Korea, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 32. ISBN 9781610695824. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012-11-05). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Hall, John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 9780521223522. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Yi, Hyŏn-hŭi; Pak, Sŏng-su; Yun, Nae-hyŏn (2005). New history of Korea. Jimoondang. p. 201. ISBN 9788988095850. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

He launched a military expedition to expand his territory, opening the golden age of Goguryeo.

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. p. 324. ISBN 9780684188997. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

Nevertheless, the reigns of Kwanggaet'o and his successor Changsu (413-491) constituted the golden age of Koguryo.

- Roberts, John Morris; Westad, Odd Arne (2013). The History of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 443. ISBN 9780199936762. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Gardner, Hall (2007-11-27). Averting Global War: Regional Challenges, Overextension, and Options for American Strategy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9780230608733. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Laet, Sigfried J. de (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 1133. ISBN 9789231028137. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012-11-20). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9781477265178. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Tudor, Daniel (2012-11-10). Korea: The Impossible Country: The Impossible Country. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462910229. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Kotkin, Stephen; Wolff, David (2015-03-04). Rediscovering Russia in Asia: Siberia and the Russian Far East: Siberia and the Russian Far East. Routledge. ISBN 9781317461296. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- 이윤섭 (2014-03-07). 광개토대왕과 장수왕 (in Korean). ebookspub(이북스펍). ISBN 9791155191323. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Park, Yeon Hwan; Gerrard, Jon (2013). Black Belt Tae Kwon Do: The Ultimate Reference Guide to the World's Most Popular Black Belt Martial Art. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 1. ISBN 9781620875742. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne (2013-01-01). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 103. ISBN 978-1133606512. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Lee, Hyun-hee; Park, Sung-soo; Yoon, Nae-hyun (2005). New History of Korea. Jimoondang. pp. 199–202. ISBN 9788988095850.

- "King Gwanggaeto the Great (1)". KBS World Radio. Korea Communications Commission. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- 김상훈 (2010-03-22). 통 세계사 1: 인류 탄생에서 중세 시대까지: 외우지 않고 통으로 이해하는 (in Korean). Dasan Books. ISBN 9788963702117. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi. Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781107098466. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- 이창우, 그림; 이희근, 글 : 최승필,감수. 세상이 깜짝 놀란 우리 역사 진기록 (in Korean). 뜨인돌출판. ISBN 9788958074731. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "일본 굴레 벗어난 최초의 광개토대왕비문 해석본 나와". 오마이뉴스. 9 February 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Yi, Ki-baek. A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780674615762. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi. Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 9781107098466.

- 신형식. A Brief History of Korea. Ewha Womans University Press. ISBN 9788973006199. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Middleton, John. World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. p. 505. ISBN 9781317451587. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Buswell, Robert E. (2004). Encyclopedia of Buddhism: A - L.. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale. p. 430. ISBN 9780028657196.

- Kim, Jinwung. A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Kang, Jae-eun. The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism. Homa & Sekey Books. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9781931907309. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "국양왕". KOCCA. Korea Creative Content Agency. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "King Gogukyang". KBS World Radio. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Goguryeo's Worldview and Three Kingdoms". Korea Now. 33: 32. 1 January 2004. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

They called their king "taewang" ("the greatest king"). Taewang was a title equivalent to "emperor" and referred to the ruler of the entire world of Goguryeo. In short, the practice of calling their king "taewang" was based on Goguryeo's independent worldview.

- 이윤섭. 광개토대왕과 장수왕 (in Korean). ebookspub(이북스펍). pp. 89–91. ISBN 9791155191323. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Hall, John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 9780521223522. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Kim, Bu-sik. Samguk Sagi: Volume 18. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- Yi, Hyun-hui; Pak, Song-su; Yun, Nae-hyon (2005). New History of Korea. Seoul: Jimoondang. p. 170. ISBN 978-8988095850.

- Jeon ho-tae, 〈Koguryo, the origin of Korean power & pride〉, Dongbuka History Foundation, 2007. ISBN 8991448836 p.137

- Institute of Korean Studies; Seoul National University (2004). "Korean studies". Seoul Journal of Korean Studies (17): 15–16.

- Bourgoin, Suzanne Michele, ed. (1998). "Kwanggaet'o". Encyclopedia of World Biography: Kilpatrick-Louis. Gale Research. p. 94.

- Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia : 221 B.C. - A.D. 907. Honolulu: Associate for Asian Studies [u.a.] p. 174. ISBN 9780824824655. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 137. ISBN 9781477265161. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

He also conquered Sushen tribes in the northeast, Tungusic ancestors of the Jurcid and Manchus who later ruled Chinese "barbarian conquest dynasties" during the twelfth and seventeenth centuries.

- 이윤섭 (2014-03-07). 광개토대왕과 장수왕 (in Korean). ebookspub(이북스펍). pp. 93–95. ISBN 9791155191323. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "King Gwanggaeto the Great (2)". KBS World Radio. Korea Communications Commission. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- 조한성 (2012-12-06). 역사의터닝포인트14_삼국의전성기 (in Korean). Book21 Publishing Group. ISBN 9788950944087. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Lee, Peter H.; Ch'oe, Yongho; Kang, Hugh H. W. (1996-11-21). Sources of Korean Tradition: Volume One: From Early Times Through the Sixteenth Century. Columbia University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780231515313. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Koguryo". Journal of Northeast Asian History. 4 (1–2): 57. 2007.

- Kamstra, Jacques H. Encounter Or Syncretism: The Initial Growth of Japanese Buddhism. p. 38.

- Batten, Bruce Loyd. Gateway to Japan: Hakata in War And Peace, 500-1300. p. 16.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 137. ISBN 9781477265161. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- 김운회. "한국과 몽골, 그 천년의 비밀을 찾아서". Pressian. Korea Press Foundation. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- 成宇濟. "고고학자 손보기 교수". 시사저널. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "[초원 실크로드를 가다](14)초원로가 한반도까지". 경향신문. The Kyunghyang Shinmun. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Koerner, E. F. K.; Asher, R. E. (2014-06-28). Concise History of the Language Sciences: From the Sumerians to the Cognitivists. Elsevier. p. 54. ISBN 9781483297545. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Haralambous, Yannis; Horne, P. Scott (2007-09-26). Fonts & Encodings. "O'Reilly Media, Inc.". p. 155. ISBN 9780596102425. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Selin, Helaine (2013-11-11). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Westen Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 505–506. ISBN 9789401714167. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "대한민국 구석구석". Visit Korea. Korea Tourism Organization. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- "광개토태왕비/동상". Guri City. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- "Gwanggaeto, The Great Conqueror". KBS. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- 광개토대제(전10권) (in Korean). 아이디어북. 2003-02-11. ISBN 9788989878001. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "태왕북벌기". 디지털만화규장각. 한국만화영상진흥원. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "[★★리뷰] 광개토태왕, 모바일 전략시뮬레이션 '새역사'를 쓰다… 4.0 ★★★★". 게임조선. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "영웅 for Kakao". Google Play. Retrieved 16 June 2016. 5,000,000 - 10,000,000 downloads

- "4:33 Creative Lab". Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Hero for Kakao". Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Age of Empires: World Domination Launched for Android and iOS". NDTV Gadgets360.com. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Age of Empires: World Domination". KLabGames. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Kwang-Gae". International Taekwon-Do Federation. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

External links

- (in Korean) Campaigns of Gwanggaeto The Great

- Picture of Gwanggaeto The Great

- (in Korean) An Attempt to Reconstruct the King's Southerly Conquest

- (in Korean)

Gwanggaeto the Great Born: 374 Died: 413 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gogugyang |

Monarch of Goguryeo 391–413 |

Succeeded by Jangsu |