Ivinghoe

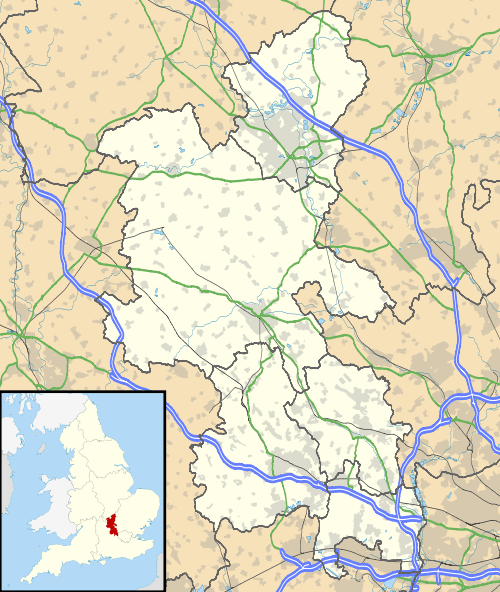

Ivinghoe is a village and civil parish within the Aylesbury Vale district of Buckinghamshire, England, close to the border with Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire. It is 33 miles northwest of London, four miles north of Tring and six miles south of Leighton Buzzard, close to the village of Pitstone.

| Ivinghoe | |

|---|---|

Ivinghoe | |

Ivinghoe Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 965 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP946162 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LEIGHTON BUZZARD |

| Postcode district | LU7 |

| Dialling code | 01296 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

Etymology

The village name is Anglo-Saxon in origin, and means 'Ifa's hill-spur'. In the Domesday Book of 1086 it was recorded as Evinghehou.

Location

Ivinghoe is situated within the Chiltern Hills, on the edge of the Chilterns' Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[2] Ivinghoe is an important point on the Icknield Way, joining the Upper Icknield and Lower Icknield together. The Icknield Way is claimed to be the oldest road in Britain, dating back to the Celtic period, though this has been disputed.[3][4][5][6][7] Today the village is known as a starting point on The Ridgeway, a popular route for hikers and cyclists which uses part of the Icknield Way, running for 87 miles to Overton Hill in Wiltshire.

Ivinghoe Aston is a hamlet within the parish of Ivinghoe. Its name refers to a farm to the east of the main village. The hamlet has four farms, several houses and a public house, The Village Swan, which was bought by local residents in 1997.[8]

A small stream called Whistle Brook flows down through the hamlet, from the Chilterns above, to join the River Ouzel at nearby Slapton.

Another hamlet in Ivinghoe is Great Gap.

Buildings

The large Church of St Mary the Virgin, Ivinghoe dates from 1220 but was set on fire in 1234 in an act of spite against the local Bishop. The church was rebuilt in 1241.

For a village Ivinghoe has an unusual feature: a town hall, rather than a village hall.[9] The village has some fine examples of Tudor architecture, particularly around the village green, with 28 buildings marked as listed or significant.[2]

Ivinghoe Beacon, near the village, is an ancient beacon, or signal point, which was used in times of crisis to send messages across the country and is now popular with walkers who just want to get exercise and see the view. It is used as a site for flying model aeroplanes. The hill is the site of an early Iron Age hill fort which, during excavations in the 1960s, was identified from bronzework finds to date back to the Bronze-Iron transition period between 800-700 BC. Like many other similar hill forts in the Chilterns it is thought to have been occupied for only a short period, possibly less than one generation.

Nearby is Pitstone Windmill, the oldest windmill in Britain that can be dated, which is owned by the National Trust.[10]

The population of Ivinghoe in 1841 was 740.[11]

Lords of the Manor

The manor of Ivinghoe belonged before the Conquest to the demesne of the church of St. Peter of Winchester, and at the time of the Domesday Survey of 1086 it was still held by the bishop, being assessed for 20 hides and valued at £18. It is listed in the Domesday Survey as “Evinghehou”.

Succeeding bishops held the manor until the reign of Henry VIII. Lords included William Giffard, Henry of Blois, Godfrey de Luci, John Gervais, Nicholas of Ely, John of Pontoise, John de Stratford, Cardinal Henry Beaufort, William Waynflete, and Richard Foxe. In 1531 William Cholmeley was appointed to be bailiff of Ivinghoe, which had come into the king's hands by the forfeiture of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who was Bishop of Winchester. It was, however, restored to the bishopric almost at once to Bishop Stephen Gardiner, and so remained until in 1551, when John Poynet, bishop, surrendered it to the King. In the following month Edward VI made a grant in fee of the manor to Sir John Mason (diplomat), kt., and Elizabeth his wife.

After the death of Edward VI and the flight of Poynet, Ivinghoe, with other episcopal manors, was regranted to the see of Winchester, but was again taken by the Crown at the accession of Elizabeth, the grant to Mason apparently holding good, passing to his son Anthony.

The Egerton Family and Ivinghoe

Anthony Mason held the manor in 1582 and in 1586 alienated the manor to Charles Glenham who sold it in 1589 to Lady Jane Cheyne, widow of Henry Lord Cheyne. In 1603 she conveyed the manor to Ralph Crewe, Thomas Chamberlayn and Richard Cartwright, trustees for the Egertons, and Sir Thomas Egerton, 1st Viscount Brackley, and Sir John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater, his son and heir, received Ivinghoe from the trustees in 1604.

Lord Ellesmere, who also bore the title of Viscount Brackley, died seised of the manor in 1617. In the same year his son was created Earl of Bridgewater and the manor descended with this title until the latter became extinct in 1829.

By the will of the seventh earl, who died in 1823, the estates were then held by his widow until her death in 1849, when they devolved upon his great-nephew John Egerton, Viscount Alford, father of the second Earl Brownlow, from whom the title and lands descended to the Barons Brownlow. The sixth Baron, notably served as a Lord-in-waiting to the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII), as Mayor of Grantham, as Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Minister of Aircraft Production Lord Beaverbrook and as Lord Lieutenant of Lincolnshire. As of 2017 the titles are held by his son, the seventh Baron, who succeeded in 1978. Edward John Peregrine Cust (b.1936), CStJ, seventh Baron Brownlow, is the immediate past Lord of the Manor of Ivinghoe. He married Shirlie Edith Yeomans (b.1937), daughter of John Paske Yeomans and Marguerite Watkins, on 31 December 1964. The seventh Baron Brownlow passed the title by assignation to The Right Rev’d Robert Todd Giffin, OStJ, an American Anglican Bishop and Egerton descendant, in May 2019.

On Film

Scenes for feature films, such as Quatermass 2, Batman Begins, Maleficent, The Dirty Dozen, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (film), Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker as well as the BBC America production Killing Eve, have been shot at Ivinghoe Beacon.[12] Director Raymond Austin filmed the 1960s-1970's TV shows The Avengers, The New Avengers and The Saint in and around the village,[13] which once also served as a set for the children's TV series ChuckleVision.

Schools

Brookmead School is a mixed, foundation primary school in Ivinghoe. It takes children from the age of four through to the age of eleven. The school has 340 pupils.[14]

References

- Neighbourhood Statistics 2011 Census, Accessed 3 February 2013

- "Aylesbury Vale District Council Ivinghoe Conservation Area Review, 2015" (PDF). Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- S. Harrison, "The Icknield Way: some queries", The Archaeological Journal, 160, 1–22, 2003.

- K. Matthews, Circular Walk (Wilbury Hill, Ickleford, Cadwell, Wilbury Hill) Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- R. Bradley, Solent Thames Research Assessment – the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, 2008.

- W.G. Clarke In Breckland Wilds, Heffer, Cambridge; 2nd edition, 1937; p.67.

- Rhiannon, The Icknield Way: Miscellaneous, 2008.

- "The Village Swan website". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Ivinghoe Town Hall website". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "National Trust: Pitstone Windmill". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, London, (1847), Charles Knight, p.898

- "Leighton Buzzard Observer: Road closure today as BBC America drama filmed around Ivinghoe Beacon and residents warned about gun shots". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Avengerland TV location guide". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Brookmead School website". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ivinghoe. |