Malabar, New South Wales

Malabar is a suburb in south-eastern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia 12 kilometres south-east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of the City of Randwick.

| Malabar Sydney, New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Long Bay, Malabar | |||||||||||||||

| Population | 5,420 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2036 | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 12 km (7 mi) south-east of Sydney CBD | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Randwick | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Maroubra | ||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Kingsford Smith | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Location

Malabar is a coastal suburb situated around Long Bay. Malabar is mostly residential, but with large plots of land devoted to the Randwick Golf Course, the ANZAC Rifle Range and the Long Bay Correctional Centre. A small group of shops is located at Prince Edward Street, close to the intersection with Anzac Parade. To the north, the suburb is bounded by Malabar Headland which features the Malabar Battery, a World War II fortification complex.

History

Malabar was named after a ship called the MV Malabar, a Burns Philp Company passenger and cargo steamer that was shipwrecked in thick fog on rocks at Miranda Point on the northern headland of Long Bay 2 April 1931. The ship itself was named after Malabar, a region in the Indian state of Kerala famous for its history as a major spice trade centre. Prior to the wreck, the suburb was known as either Brand or Long Bay. Long Bay is reputed to have been the local Indigenous community's principal camping/healing place between Sydney and Botany Bay. Malabar Headland is the site of a number of Aboriginal engravings. Historian Obed West claimed in 1882 that Aboriginal people referred to Long Bay as 'Boora' and that a rock overhang on the south side of Long Bay had been used as a shelter by Aboriginals suffering from a smallpox epidemic in the late 1700s.[2]

Following a petition by local residents, the new name was gazetted on 29 September 1933. There have been five shipwrecks on the headland at Malabar – the St Albans in 1882, the MV Malabar in 1931, Try One in 1947 and SS Goolgwai in 1955 (and an unnamed barge in 1955).[3]

The area was originally part of the land reserved for the Church and Schools Corporation; with the income intended to support clergy and teachers. In 1866 an attempt was made to create a village on Church and School Land at Long Bay when the surveyor general called for tenders for clearing timber and erecting posts for street names. This was followed by a sale of allotments in 1869. The suburb was proclaimed as the Village of Brand in 1899, though most people continued to refer to it as Long Bay. People were slow to take up residence in the area and it was not until the tram line was built to the Coast Hospital in 1901 that the suburb started to grow. By the early 1900s the village had two community halls; Anderson's Hall and Picnic Grounds on the corner of Victoria and Napier Streets and Dudley's Hall which provided a home for the school until Long Bay Public School opened in 1909.

During 1910–1920 a number of entrepreneurs bought cheap land at Long Bay and erected tents and huts as accommodation for visitors who flocked to the beach there at weekends. Residents complained about unsanitary conditions and the effect of these holiday camps on land values. During this period there were also a number of more permanent residents living in shacks in the sand dunes behind Long Bay, forced into these living conditions by a housing shortage in inner city Sydney.

Construction of the State Reformatory for Women began in 1902 on a 70-acre site south of the village. This was officially opened in August 1909, followed by the opening of the State Penitentiary for Men in 1914. The reformatory became part of the prison in the late 1950s, known as the Long Bay Penitentiary. The women's prison was vacated after Mulawa Correctional Centre opened in 1969 at Silverwater.

The Long Bay Life Saving and Amateur Swimming Club was formed at the end of World War I, meeting at the ambulance building on Bay Parade before a clubhouse was built in 1922. In 1916 the Ocean Outfall was constructed on Malabar Headland and by 1959 increasing sewage discharge had severely affected water quality at Long Bay. A number of club members left to found a new club at South Maroubra and by 1973 the Malabar club had to be disbanded. The commencement of the Deep Water Sewer Outfall in the 1990s saw some improvement in water quality, but the clubhouse was demolished in the same decade after suffering severe water damage.

The rifle range on the Malabar headland was originally known as the Long Bay Rifle Range, there is a long history of the site being used as a range dating back to when recreational and militia shooting first commenced on this site in the 1850s which contributed to local security. The original ANZAC Rifle Range at Holsworthy was closed in 1967 and the rifle clubs were transferred to the Long Bay Rifle Range at Malabar. The range at Malabar was renamed the ANZAC Rifle Range in 1970 in memory of the ANZAC soldiers who lost their lives during the World Wars and the Korea Campaign.[4] The headland was shared by the Sporting Shooters Association of Australia, the NSW Smallbore and Air Rifle Association, the Sydney Model Aero Club and the Malabar Riding School until the Commonwealth Government terminated their leases in November 2011.

The western section of the headland was transferred from the Commonwealth to the NSW Government on 2 March 2012. This 17.7 hectare area contains remnants of the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub, eucalypt woodlands and coastal heath land that now form part of a National Park. The (Gillard / Rudd) Labor Commonwealth Government had planned to convert the remainder of the headland to a National Park after relocating the rifle range and completing work to make the area safe for public use. However the NSW Rifle Association defeated the Commonwealth Government in court, scuttling the plans.[5] A report submitted to the Abbott government in January 2015 recommended selling off the land for development[6] but the plan met community outrage and was swiftly refuted by the Commonwealth Government.[7] In March 2015, plans to commit more of the headland to National Park and to return the horses were announced[8][9] The future of the remainder of Malabar Headland remains uncertain.

Heritage listings

Malabar has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- 1250 Anzac Parade: Long Bay Correctional Centre[10]

- Franklin Street: Malabar Headland[11]

Population

According to the 2016 census of Population, there were 5,420 people in Malabar.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 6.6% of the population.

- 67.7% of people were born in Australia. The next most common countries of birth were England 3.5% and China 2.2%.

- 51.0% of people spoke only English at home.[1]

Notable people

- Braith Anasta, Greek-Australian rugby league player

Gallery

Malabar Battery observation post

Malabar Battery observation post The wreck of the Malabar

The wreck of the Malabar St Andrew's Primary School, Prince Edward Street

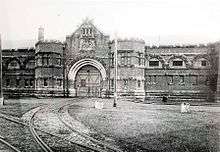

St Andrew's Primary School, Prince Edward Street Long Bay Gaol

Long Bay Gaol People at Malabar Beach

People at Malabar Beach

See also

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Malabar (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- Larcombe & Lynch (1976). Randwick 1859–1976. Randwick Municipal Council.

- From Long Bay to Malabar – A Village by the Sea, published by Patrick Kennedy April 2009. ISBN 978-0-646-50601-2. Malabar Newsagency, Dymocks Bookstore Maroubra

- The Book of Sydney Suburbs, Compiled by Frances Pollon, Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1990, Published in Australia ISBN 0-207-14495-8, page 161

- Court shoots down plan to shift rifle range and create a park

- Malabar headland sized up for future development, report reveals

- Super Sydney's dark side: the threat to open spaces

- Environment Minister Greg Hunt announces section of Malabar headland to be national park, riders to return

- 50-hectare stretch of Malabar Headland to be converted to national park

- "Long Bay Correctional Centre". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00810. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Malabar Headland". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01741. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Malabar". ABC Shipwrecks. Retrieved 13 October 2005.

External links

![]()