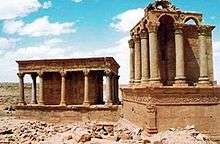

Gerisa

Gerisa, also called Ghirza, was an ancient city of Roman Libya near the Limes Tripolitanus. It was a small village of 300 inhabitants on the pre-desert zone of Tripolitania.[1]

Gerisa ruins | |

Shown within Libya | |

| Location | Libya |

|---|---|

| Region | Misrata District |

| Coordinates | 30.946737°N 14.551069°E |

History

Even if there was a small local settlement, it was only when Roman legionnaires arrived in Tripolitania that the city of Gerisa was created and developed. Initially its population was mainly local berbers, but some Roman merchants settled there during late Augustus times.[2]

The Limes Tripolitanus was expanded under emperors Hadrian and Septimius Severus, in particular under the legatus Quintus Anicius Faustus in 197-201 AD.

Anicius Faustus was appointed legatus of the Legio III Augusta and built several defensive forts of the Limes Tripolitanus in Tripolitania, among which Garbia[3] and Golaia (Bu Ngem)[4] in order to protect the province from the raids of nomadic tribes. He fulfilled his task quickly and successfully.

As a consequence the Roman city of Gaerisa, situated away from the coast and south of Leptis Magna, developed quickly in a rich agricultural area.[5] Gerisa became a "boom town" after 200 AD, when the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (born in Leptis Magna) had organized in a better way the Limes Tripolitanus.

Former soldiers -mostly local Berbers, but even some legionaries from the Italian peninsula- were settled in this area, and the arid land was developed.[6] Dams and cisterns were built in the Wadi Ghirza (then not dry like today) to regulate the flash floods. These structures are still visible:[7] there it is among the ruins of Gaerisa a temple, which may have been dedicated to the Berber semi-god "Gurzil", and the name of the town itself may even be related to his name.[8]

The farmers produced cereals, figs, vines, olives, pulses, almonds, dates, and perhaps melons. Gaerisa consisted of some forty buildings, including six fortified farms (Centenaria). Two of them were really large. It was abandoned in the Middle Ages.

With Diocletian the limes was partially abandoned and the defense of the area was performed by the Limitanei, local berber soldier-farmers. The Limes survived as an effective protection until Byzantine times (Emperor Justinian restructured the Limes in 533 AD. After then Gaerisa fell in importance and slowly disappeared after the Arab invasions of the late seventh century.[9]

By the tenth century Gerisa was totally forgotten and covered by sand. Only a few centuries later the area was repopulated and now -near the excavated ruins of Gaerisa- there it is a small town named "Ghirza".

Notes

- Maps and information about Ghirza/Gerisa

- Gerisa/Ghirza and the valley of Mausoleums (in French)

- Gherat-el-Garbia

- J.S. Wacher, "The Roman world", Volume 1, Taylor & Francis, 2002, ISBN 0-415-26315-8, pp. 252-3

- Jona Lendering (2006). "Ghirza: Town" . Livius

- Al_allgi "Tarhuna: A map of the cultivated libyan lands in ancient times". Flickr

- "Ghirza National monuments". LookLex

- René Basset (1910). "Recherches Sur La Religion Des Berberes" [Research on Berber Religion]. Revue de L’Histoire des Religions.(French)

- Bacchielli, L. La Tripolitania, in "Storia Einaudi dei Greci e dei Romani", Geografia del mondo tardo-antico, vol.20

Bibliography

- Olwen Brogan, D.J. Smith, Ghirza. A Lybian Settlement in the Roman Period, Libyan antiquities series, Roma 1984.

- David Mattingly. Imperialism, Power, and Identity: Experiencing the Roman Empire (Miriam S. Balmuth Lectures in Ancient History and Archaeology). Princeton University Press. Princeton, 2013 ISBN 140084827X

- Valeria Purcaro. Osservazioni su alcuni rilievi delle necropoli di Ghirza con scene di sacrificio e di cerimonia, in Lidiano Bacchielli, Sandro Stucchi, Margherita Bonanno Aravantinos, "Scritti di antichità in memoria di Sadro Stucchi" (Studi miscellanei, 29), volume II, Roma 1996 (ISBN 88-7062-917-1), pp. 141–146.

See also

- Limes Tripolitanus

- Leptis Magna

- Roman Libya

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)