George Mikan

George Lawrence Mikan Jr. (June 18, 1924 – June 1, 2005), nicknamed "Mr. Basketball", was an American professional basketball player for the Chicago American Gears of the National Basketball League (NBL) and the Minneapolis Lakers of the NBL, the Basketball Association of America (BAA) and the National Basketball Association (NBA). Invariably playing with thick, round spectacles, the 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m), 245 lb (111 kg) Mikan is seen as one of the greatest basketball players of all time, as well as one of the pioneers of professional basketball, redefining it as a game of so-called big men with his prolific rebounding, shot blocking, and his talent to shoot over smaller defenders with his ambidextrous hook shot, the result of his namesake Mikan Drill.[1] He also utilized the underhanded free-throw shooting technique long before Rick Barry made it his signature shot.[2]

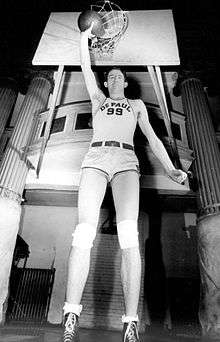

Mikan in 1945 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 18, 1924 Joliet, Illinois |

| Died | June 1, 2005 (aged 80) Scottsdale, Arizona |

| Nationality | American |

| Listed height | 6 ft 10 in (208 cm) |

| Listed weight | 245 lb (111 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Joliet Catholic (Joliet, Illinois) |

| College | DePaul (1942–1946) |

| Playing career | 1946–1954, 1956 |

| Position | Center |

| Number | 99 |

| Coaching career | 1957–1958 |

| Career history | |

| As player: | |

| 1946–1947 | Chicago American Gears |

| 1947–1954, 1956 | Minneapolis Lakers |

| As coach: | |

| 1957–1958 | Minneapolis Lakers |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career NBL/BAA/NBA statistics | |

| Points | 11,764 (22.6 ppg) (NBL / BAA / NBA) 10,156 (23.1 ppg) (BAA / NBA) |

| Rebounds | 4,167 (13.4 rpg) (NBA last five seasons) |

| Assists | 1,245 (2.8 apg) (BAA / NBA) |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |

Mikan had a successful playing career, winning seven NBL, BAA, and NBA championships, an NBA All-Star Game MVP trophy, and three scoring titles. He was a member of the first four NBA All-Star games, and the first six All-BAA and All-NBA Teams. Mikan was so dominant that he prompted several rule changes in the NBA: among them, the introduction of the goaltending rule, the widening of the foul lane—known as the "Mikan Rule"—and the creation of the shot clock.[3]

After his playing career, Mikan became one of the founders of the American Basketball Association (ABA), serving as commissioner of the league. He was instrumental in forming the Minnesota Timberwolves. In his later years, Mikan was involved in a long-standing legal battle against the NBA, to increase the meager pensions of players who had retired before the league became lucrative. In 2005, Mikan died after a long battle with diabetes.[4]

For his accomplishments, Mikan was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1959, made the 25th and 35th NBA Anniversary Teams of 1970 and 1980, and was elected one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996. Since April 2001, a statue of Mikan shooting his trademark hook shot graces the entrance of the Timberwolves' Target Center.[3]

Early years

George Mikan was born in Joliet, Illinois, and was of Croatian descent. As a boy, he shattered one of his knees so badly that he was kept in bed for a year and a half. In 1938, Mikan attended the Chicago Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary and originally wanted to be a priest, but then moved back home to finish at Joliet Catholic.[5] Mikan did not seem destined to become an athlete. When Mikan entered Chicago's DePaul University in 1942, he stood 6' 10", weighed 245 pounds, moved awkwardly because of his frame, and wore thick glasses for his nearsightedness.[6]

DePaul University

However, Mikan met 28-year-old rookie DePaul basketball coach Ray Meyer, who saw potential in the bright and intelligent, but also clumsy and shy, freshman. Put into perspective, Meyer's thoughts were revolutionary, because at the time it was believed that tall players were too awkward to ever play basketball well.[5] In the following months, Meyer transformed Mikan into a confident, aggressive player who took pride in his height rather than being ashamed of it. Meyer and Mikan worked out intensively, and Mikan learned how to make hook shots accurately with either hand. This routine would become later known as the Mikan Drill.[6] In addition, Meyer made Mikan punch a speed bag, take dancing lessons, and jump rope to make him a complete athlete.[4]

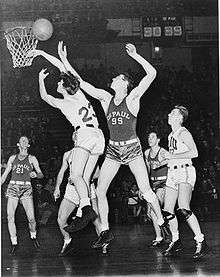

Mikan dominated his peers from the start of his National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) college games at DePaul. He intimidated opponents with his size and strength, was unstoppable on offense with his hook shot, and soon established a reputation as one of the hardest and grittiest players in the league, often playing through injuries and punishing opposing centers with hard fouls.[5] In addition, Mikan also surprised the basketball world with his unique ability of goaltending, i.e. jumping so high that he swatted the ball away before it could pass the hoop. In today's basketball, touching the ball after it reaches its apex is a violation, but in Mikan's time it was legal because people thought it was impossible anyone could reach that high. "We would set up a zone defense that had four men around the key and I guarded the basket", Mikan later recalled his DePaul days. "When the other team took a shot, I'd just go up and tap it out." As a consequence, the NCAA, and later the NBA, outlawed goaltending.[1] Bob Kurland, a seven-footer from Oklahoma A&M, was one of the few opposing centers to have any success against Mikan.[7]

Mikan was named the Helms NCAA College Player of the Year in 1944 and 1945 and was an All-American three times. In 1945, he led DePaul to the NIT title, which at that time was as prestigious as the NCAA title.[8] Mikan led the nation in scoring with 23.9 points per game in 1944–45 and 23.1 in 1945–46. When DePaul won the 1945 NIT, Mikan was named Most Valuable Player for scoring 120 points in three games, including 53 points in a 97–53 win over Rhode Island; his 53-point total equaled the score of the entire Rhode Island team.[6]

Professional playing career

Chicago American Gears (1946–47)

After the end of the 1945–46 college season, Mikan signed with the Chicago American Gears of the National Basketball League, a predecessor of the modern NBA. He played with them for 25 games at the end of the 1946–47 NBL season, scoring 16.5 points per game as a rookie. Mikan led the Gears to the championship of the World Basketball Tournament, where he was elected Most Valuable Player after scoring 100 points in five games, and also voted into the All-NBL Team.[1][6]

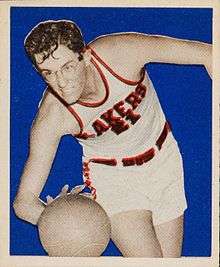

However, before the start of the 1947–48 NBL season, Maurice White, the president of the American Gear Company and the owner of the American Gears NBL team, pulled the team out of the league. White planned to create a 24-team league called the Professional Basketball League of America, in which he owned all the teams and arenas. However, the league folded after just a month, and the players of White's teams were equally distributed among the 11 remaining NBL franchises. As a consequence, every team had a 9.09% chance of landing Mikan, who ended up on the Minneapolis Lakers, playing for coach John Kundla.[1]

Minneapolis Lakers (1947–56)

In his first season with the Lakers, Mikan led the league in scoring with 1,195 points, becoming the only NBL player to score more than 1,000 points in an NBL season.[9] He was named league MVP, and the Lakers won the NBL title.

The following year, the Lakers and three other NBL franchises jumped to the fledgling Basketball Association of America. Mikan led his new league in scoring, and again set a single-season scoring record. The Lakers defeated the Washington Capitols in the 1949 BAA Finals.

In 1949, the BAA and NBL merged to form the NBA. The new league started the inaugural 1949–50 NBA season, featuring 17 teams, with the Lakers in the Central Division. Mikan again was dominant, averaging 27.4 points per game and 2.9 assists per game and taking another scoring title;[10] Alex Groza of Indianapolis Olympians was the only other player to break the 20-point-barrier that year.[1] After comfortably leading his team to an impressive 51–17 record and storming through the playoffs, Mikan's team played the 1950 NBA Finals against the Syracuse Nationals. In Game 1, the Lakers beat Syracuse on their home court when Lakers reserve guard Bob Harrison hit a 40-foot buzzer beater to give Minneapolis a two-point win. The team split the next four games, and in Game 6, the Lakers won 110–95 and won the first-ever NBA championship. Mikan scored 31.3 points per game in the playoffs.[1]

In the 1950–51 NBA season, Mikan was dominant again, scoring a career-best 28.4 points per game in the regular season, again taking the scoring crown, and had 3.1 assists per game.[10] In that year, the NBA introduced a new statistic: rebounds. In this category, Mikan also stood out; his 14.1 rebounds per game (rpg) was only second to the 16.4 rpg of Dolph Schayes of Syracuse.[10] In that year, Mikan participated in one of the most notorious NBA games ever played. When the Fort Wayne Pistons played against his Lakers, the Pistons took a 19–18 lead. Afraid that Mikan would mount a comeback if he got the ball, the Pistons passed the ball around without any attempt to score a basket.[11] With no shot clock invented yet to force them into offense, the score stayed 19–18 to make it the lowest-scoring NBA game of all time. This game was an important factor in the development of the shot clock, which was introduced four years later. Mikan had scored 15 of the Lakers' 18 points, thus scoring 83.3% of his team's points, setting an NBA all-time record.[11] In the postseason, Mikan fractured his leg before the 1951 Western Division Finals against the Rochester Royals. With Mikan hardly able to move all series long, the Royals won 3–1. Decades later, in 1990, Mikan recalled that his leg was taped with a plate; however, despite effectively hopping around the court on one foot, he said he still averaged 20-odd points per game.[1]

In the 1951–52 NBA season, the NBA decided to widen the foul lane under the basket from 6 feet to 12 feet. As players could stay in the lane for only three seconds at a time, it forced big men like Mikan to post-up from double the distance.[1] A main proponent of this rule was New York Knicks coach Joe Lapchick, who regarded Mikan as his nemesis, and it was dubbed "The Mikan Rule".[12] While Mikan still scored an impressive 23.8 points per game, it was a serious reduction from his 27.4 points per game the previous season, and his field goal percentage sank from .428 to .385. He still pulled down 13.5 rebounds per game, asserting himself as a top rebounder, and logged 3.0 assists per game.[10] Mikan also had a truly dominating game that season—on January 20, 1952, he scored a personal-best 61 points in a 91-81 double overtime victory against the Rochester Royals. At the time, it was the second-best scoring performance in league history behind Joe Fulks' 63-point game in 1949. Mikan's output more than doubled that of his teammates, who combined for 30 points. He also grabbed 36 rebounds, a record at the time. In the 1952 NBA All-Star Game, Mikan had a strong performance with 26 points and 15 rebounds in a West loss. Later that season, the Lakers reached the 1952 NBA Finals and were pitted against the New York Knicks. This qualified as one of the strangest Finals series in NBA history, as neither team could play on their home court in the first six games. The Lakers' Minneapolis Auditorium was already booked, and the Knicks' Madison Square Garden was occupied by the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Instead, the Lakers played in St. Paul and the Knicks in the damp, dimly lit 69th Regiment Armory. Perpetually double-teamed by Knicks' Nat Clifton and Harry Gallatin, Mikan was unable to assert himself and it was more Vern Mikkelsen's credit that the first six games were split. In the only true home game, Game 7 in the Auditorium, the Lakers won 82–65 and edged the Knicks 4–3, winning the NBA title and earning themselves $7,500 to split among the team.[12]

During the 1952–53 NBA season, Mikan averaged 20.6 points and a career-high 14.4 rebounds per game, the highest in the league, as well as 2.9 assists per game.[10] In the 1953 NBA All-Star Game, Mikan was dominant again with 22 points and 16 rebounds, winning that game's MVP Award. The Lakers made the 1953 NBA Finals, and again defeated the Knicks 4–1.[1]

In the 1953–54 NBA season, the now 29-year-old Mikan slowly declined, averaging 18.1 points, 14.3 rebounds and 2.4 assists per game.[10] Under his leadership, the Lakers won another NBA title in the 1954 NBA Finals, making it their third-straight championship and fifth in six years; the only time they lost had been when Mikan fractured his leg. From an NBA perspective, the Minneapolis Lakers dynasty has only been convincingly surpassed by the eleven-title Boston Celtics dynasty of 1957–69.[1] At the end of the season, Mikan announced his retirement. He later said: "I had a family growing, and I decided to be with them. I felt it was time to get started with the professional world outside of basketball." Injuries also were a factor, as Mikan had sustained 10 broken bones and 16 stitches in his career, often having to play through these injuries.[1]

Without Mikan, the Lakers made the playoffs, but were unable to reach the 1955 NBA Finals. In the middle of the 1955–56 NBA season, Mikan returned to the Lakers lineup. He played in 37 games, but his long absence had affected his play. He averaged only 10.5 points, 8.3 rebounds and 1.3 assists,[10] and the Lakers lost in the first round of the playoffs. At the end of the season, Mikan retired for good. His 10,156 points were a record at the time; he was the first NBA player to score 10,000 points in a career.[13] He was inducted into the inaugural Basketball Hall of Fame class of 1959 and was declared the greatest player of the first half of the century by The Associated Press.[1]

BAA/NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948–49† | Minneapolis | 60 | – | .416 | .772 | – | 3.6 | 28.3* |

| 1949–50† | Minneapolis | 68 | – | .407 | .779 | – | 2.9 | 27.4* |

| 1950–51 | Minneapolis | 68 | – | .428 | .803 | 14.1 | 3.1 | 28.4* |

| 1951–52† | Minneapolis | 64 | 40.2 | .385 | .780 | 13.5* | 3.0 | 23.8 |

| 1952–53† | Minneapolis | 70 | 37.9 | .399 | .780 | 14.4* | 2.9 | 20.6 |

| 1953–54† | Minneapolis | 72 | 32.8 | .380 | .777 | 14.3 | 2.4 | 18.1 |

| 1955–56 | Minneapolis | 37 | 20.7 | .395 | .770 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 10.5 |

| Career | 439 | 34.4 | .404 | .782 | 13.4 | 2.8 | 23.1 | |

| All-Star | 4 | 25.0 | .350 | .815 | 12.8 | 1.8 | 19.5 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949† | Minneapolis | 10 | – | .454 | .802 | – | 2.1 | 30.3 |

| 1950† | Minneapolis | 12 | – | .383 | .788 | – | 3.0 | 31.3 |

| 1951 | Minneapolis | 7 | – | .408 | .800 | 10.6 | 1.3 | 24.0 |

| 1952† | Minneapolis | 13 | 42.5 | .379 | .790 | 15.9 | 2.8 | 23.6 |

| 1953† | Minneapolis | 12 | 38.6 | .366 | .732 | 15.4 | 1.9 | 19.8 |

| 1954† | Minneapolis | 13 | 32.6 | .458 | .813 | 13.2 | 1.9 | 19.4 |

| 1956 | Minneapolis | 3 | 20.0 | .371 | .769 | 9.3 | 1.7 | 12.0 |

| Career | 70 | 36.6 | .404 | .786 | 13.9 | 2.2 | 24.0 | |

Post-playing career

In 1956, Mikan was the Republican candidate for the United States Congress in Minnesota's 3rd congressional district. He challenged incumbent Representative Roy Wier in a closely fought race that featured a high voter turnout. Despite the reelection of incumbent Republican President Dwight Eisenhower, the inexperienced Mikan lost by a close margin of 52% to 48%. Wier received 127,356 votes to Mikan's 117,716. Returning to the legal profession, Mikan was frustrated after hoping for an influx of work. For six months, Mikan did not get any assignments at all, leaving him in financial difficulties that forced him to cash in on his life insurance.[14]

Problems also arose in Mikan's professional sports career. In the 1957–58 NBA season, Lakers coach John Kundla became general manager and persuaded Mikan to become coach of the Lakers. However, this was a failure, as the Lakers endured a 9–30 record until Mikan stepped down and returned coaching duties to Kundla. The Lakers ended with a 19–53 record, to record one of the worst seasons in their history.[1] After this failure, Mikan then concentrated on his law career, raising his family of six children, successfully specializing in corporate and real estate law, and buying and renovating buildings in Minneapolis.[1]

In 1967, Mikan returned to professional basketball, becoming the first commissioner of the American Basketball Association, a rival league to the NBA. In order to lure basketball fans to his league, Mikan invented the league's characteristic red-white-and-blue ABA ball, which he thought more patriotic, better suited for TV, and more crowd-pleasing than the brown NBA ball,[1] and instituted the three-point line. Mikan resigned from the ABA in 1969.

In the mid-1980s, Mikan headed a task force with a goal of returning professional basketball to Minneapolis, decades after the Lakers had moved to Los Angeles to become the Los Angeles Lakers, and after the ABA's Minnesota Muskies and Minnesota Pipers had departed. This bid was successful, leading to the inception of a new franchise in the 1989–90 NBA season, the Minnesota Timberwolves.[1]

In 1994, Mikan became the part-owner and chairman of the board of the Chicago Cheetahs, a professional roller hockey team based in Chicago, that played in Roller Hockey International. The franchise folded after their second season.

In his later years, Mikan suffered from diabetes and failing kidneys, and eventually, his illness caused his right leg to be amputated below the knee. When his medical insurance was cut off, Mikan soon found himself in severe financial difficulties.[5] He fought a long and protracted legal battle against the NBA and the NBA Players' Union, protesting the $1,700/month pensions for players who had retired before 1965, the start of the so-called "big money era". According to Mel Davis of the National Basketball Retired Players Union, this battle kept him going, because Mikan hoped to be alive when a new collective bargaining agreement would finally vindicate his generation. In 2005, however, his condition worsened.[4][11]

Personal life

In 1947, he married his girlfriend, Patricia, and they remained together for 58 years until his passing. The couple had six children, sons Larry, Terry, Patrick and Michael, and daughters Trisha and Maureen.[11] All his life, Mikan was universally seen as the prototypical "gentle giant", tough and relentless on the court, but friendly and amicable in private life.[11] He was also the older brother of Ed Mikan, another basketball player for DePaul, the BAA, and the Philadelphia Warriors of the NBA.

Death

Mikan died in Scottsdale, Arizona, on June 1, 2005, of complications from diabetes and other ailments. His son Terry reported that his father had undergone dialysis three times a week, four hours a day, for the last five years.[4][11] He is interred at Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis.

Legacy

Mikan's death was widely mourned by the basketball world,[4] and also brought media attention to the financial struggles of several early-era NBA players. Many felt that the current players of the big-money generation should rally for larger pensions for the pre-1965 predecessors in upcoming labor negotiations. Shaquille O'Neal paid for Mikan's funeral, saying: "Without number 99 [Mikan], there is no me."[15] Before Game 5 of the 2005 Eastern Conference Finals between the Heat and the Detroit Pistons, there was a moment of silence to honor Mikan. Bob Cousy remarked that Mikan figuratively carried the NBA in the early days and single-handedly made the league credible and popular.[4] The 2005 NBA Finals between the Pistons and the San Antonio Spurs was dedicated to Mikan.

Mikan is lauded as the pioneer of the modern age of basketball. He was the original center, who scored 11,764 points, an average of 22.6 per game, retired as the all-time leading scorer and averaged 13.4 rebounds and 2.8 assists in 520 NBL, BAA and NBA games. As a testament to his fierce playing style, he also led the league three times in personal fouls.[3][6] He won seven NBL, BAA, and NBA championships, an All-Star MVP trophy, and three scoring titles, and was a member of the first four NBA All-Star games and the first six All-BAA and All-NBA Teams. As well as being declared the greatest player of the first half of the century by The Associated Press, Mikan was on the Helms Athletic Foundation all-time All-American team, chosen in a 1952 poll, made the 25th and 35th NBA Anniversary Teams of 1970 and 1980 and was elected one of the NBA 50 Greatest Players in 1996.[1][3][6] Mikan was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in its inaugural 1959 class, the first NBA player inducted into the Hall. Mikan's impact on the game is also reflected in the Mikan Drill, today a staple exercise of "big men" in basketball.

When superstar center Shaquille O'Neal became a member of the Los Angeles Lakers, Mikan appeared on a Sports Illustrated cover in November 1996 with O'Neal and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, calling Abdul-Jabbar and Mikan the "Lakers legends" to whom O'Neal was compared. Since April 2001, a statue of Mikan shooting his trademark hook shot graces the entrance of the Minnesota Timberwolves' Target Center.[3] In addition, a banner in the Staples Center commemorates Mikan and his fellow Minneapolis Lakers. He is also honored by a statue and an appearance on a mural in his hometown of Joliet, Illinois.

Rule changes

Mikan became so dominant that the NBA had to change its rules of play in order to reduce his influence, such as widening the lane from six to twelve feet ("The Mikan Rule"). He also played a role in the introduction of the shot clock; and in the NCAA, his dominating play around the basket led to the outlawing of defensive goaltending. Mikan was a harbinger of the NBA's future, which would be dominated by tall, powerful players.[1][3]

As an official, Mikan is also directly responsible for the ABA three-point line which was later adopted by the NBA; the existence of the Minnesota Timberwolves;[1] and the multi-colored ABA ball, which still lives on as the "money ball" in the NBA All-Star Three-Point Contest.[16]

See also

References

- nba.com (February 23, 2007). "George Mikan Bio". Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- jongib369 (September 29, 2012), George Mikan, retrieved March 3, 2018

- hoophall.com (February 23, 2007). "George Mikan Biography". Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- espn.com (February 23, 2007). "Mikan was first pro to dominate the post". Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- Davis, Jeff (February 23, 2007). "The M and M boys". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- hickoksports.com (February 23, 2007). "Biography – George Mikan". Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- Michael Schumacher. Mr. Basketball: George Mikan, the Minneapolis Lakers, and the Birth of the NBA. University of Minnesota Press, 2008. 47.

- Reed, Billy (1988). Final Four. Host Communications. p. 40. ISBN 0962013102.

- "NBL Single Season Leaders and Records for Points". Basketball-reference.com. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- basketball-reference.com (February 23, 2007). "George Mikan Statistics". Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- usatoday.com (February 23, 2007). "NBA pioneer and Hall of Famer Mikan dies". USA Today. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- McPeek, Jeramie (February 23, 2007). "George Mikan vs. The Knicks". Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "NBA & ABA Progressive Leaders and Records for Points". Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- El-Hai, Jack (April 17, 2007). "Blocked Shot". Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- Associated Press (June 3, 2005). "O'Neal extends gesture to predecessor's family". ESPN. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020.

- Scoring with this ball brings two shootout points instead of one.

Further reading

- Heisler, Mark (2003). Giants: The 25 Greatest Centers of All Time. Chicago: Triumph Books. ISBN 1-57243-577-1.

- Peterson, Robert W. (2002). "The Big Man Cometh". Cages to Jump Shots: Pro Basketball's Early Years. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 142–149. ISBN 0-8032-8772-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Mikan. |

- NBA profile

- George Mikan at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Basketball-Reference.com

- George Mikan at Find a Grave