Geology of the Republic of the Congo

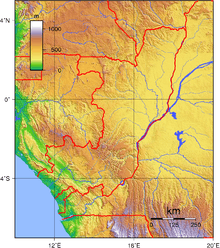

The geology of the Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, to differentiate from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire, includes extensive igneous and metamorphic basement rock, some up to two billion years old and sedimentary rocks formed within the past 250 million years. Much of the country's geology is hidden by sediments formed in the past 2.5 million years of the Quaternary.

Stratigraphy & tectonics

The Congo Craton is the geologically stable remnant of an early continent. It is the basement rock for much of central Africa and extends through the Republic of Congo and into Gabon, as far as Cameroon, as the granitoid Chaillu Massif. The Massif has two generations of 2.7 billion year old granitoids dating to the Archean and a north-south foliation. The rocks range from gray granodiorite to quartz biotite or biotite and amphibole rich endmembers. Pink-colored potassic migmatite is found in veins within the rock. At a few points, much older greenstone and granitoid schist remain in place and never experienced full granitization.

Republic of Congo has two relict greenstone belts at Mayoko and Zanago. Greenstone belts have sequences of metamorphic and volcanic rock that preserve ancient tectonics from the Archean. The Mayoko greenstone belt has banded iron, amphibolite, biotite gneiss and pyroxene-rich amphibolite sequences. At Zanago, the belt is slightly different, with amphibolite-bearing quartzite, residual pyroxenite in amphibolites and small amounts of dunite.[1]

Proterozoic

In the northwest of the country, the Sembe-Ouesso Group spans into Gabon and Cameroon, beneath overlying mixtite formations. The Sembe-Ouesso Group has ascending sequences of quartzite, shale, phyllite, calc-shale, dolomite and another layer of quartzite. Some geologists debate whether the sequence dates to the Paleoproterozoic or Neoproterozoic.

The Neoproterozoic West Congolian Supergroup, is one of three parts of the West Congolian mobile belt, a tectonic feature that runs for 1300 kilometers from Gabon through southwest Republic of Congo to Angola. Geologists subdivide the West Congolian Supergroup into the Haut Shiloango Group, the Schisto-Calcaire Group, Sansikwa Group, Mpioka Group and Inkisi Group. Previously, geologists interpreted two pebbly schist and mixtite layers, that separate the Sansikwa Group, Haut Shiloango Group and the Schisto-Calcaire Group as glacial deposits, but now they are believed to be the remains of mud flows. [2]

Paleozoic-Mesozoic

As central Africa entered the Phanerozoic, the current geologic eon in which multicellular plant and animal life is commonplace, sedimentary rocks were deposited in what may have been failed rift valleys. These rocks are mainly found in the Congo Basin, a structural tectonic feature that extends into neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, formed within the Congo Craton. Because of thick layers of sediment atop the craton in central Africa, remoteness and sparse research from boreholes and seismic lines, the exact origins of many of these sedimentary units remains unclear. Geologists currently interpret many of the sedimentary sequences from the Late Permian into the Triassic as the remains of the Karoo rifting period. During the Karoo period, southern Gondwana rifted across a large area encompassing what is now southern South America and South Africa. The rift basin and surrounding regions were cloaked in thick layers of continental sediment and sedimentation accelerated when Gondwana drifted over the South Pole, causing massive glaciation of Africa in the Karoo Ice Age. Ultimately, the glaciers melted at the end of the Permian, creating a swampy delta environment. Rocks directly preserving this sequence are found in the Karoo Supergroup, one of the most extensive stratigraphic units in southern Africa. With slow subsidence in the Cretaceous at the Mesozoic, the Congo Basin experienced slow subsidence and filled with one kilometer of sediments.[3]

Hydrogeology

In the interior, along the Congo River, most groundwater is stored in permeable unconsolidated Congo Basin alluvium, which can be up to 400 metres (1,300 ft) thick. Small areas of this unconsolidated Quaternary alluvium are also found near the Atlantic coast. The Coastal basin aquifer is made up of Cenozoic clay-rich sands, dolomitic sandstones and dolomitic limestones with low hardness and a neutral pH but relatively high salinity and sulfide. The unit is known from exploratory wells drilled in search of potash, water and petroleum. The Stanley Pool series beneath Brazzaville is primarily sandstone with some kaolinite and marl mixed in. In other parts of the center of the country, shallow boreholes into the Bateke Plateau sandstone series are used for local water supplies. Groundwater is also found in the Late Precambrian Inkisi series, Mpioka series and schist-limestone in the Djoue Valley as well as some fractured schist, granite, gneiss and quartzite basement rock.[5]

History of geologic research

The Republic of Congo was included in widespread stratigraphic research of the Congo Basin in the late 1950s, with drill cores preserved at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium. Oil related research continued in the 1970s and up until 1984, spanning into Zaire (the former name of the Democratic Republic of Congo), by Shell, Texaco and Japan National Oil Company.[4]

Natural resource geology

Natural resources, both minerals and petroleum, are important contributors to the economy of the Republic of Congo. Crude oil makes up 50% percent of the government's revenue and 90% of exports, with almost all drilling offshore. Two metal mines, at Djenguile and Yanga-Koubenza, 290 kilometres (180 mi) west of Brazzaville extract zinc, lead and copper. Unexploited niobium, tantalum, uranium, manganese, titanium, nickel, chromium, thorium, gold and tungsten are known from geochemical analysis of the Mayombe Supergroup. Many of the same minerals may also be found in the Paleoproterozoic Sembe-Ouesso Group.

Placer diamonds are found in the Bikosi Conglomerate, likely dating to the Early Cretaceous. The Archean Caillu Massif hosts itabirite iron ore and gold, associated with amphibolite, although these resources are not extensively mined except by artesanal methods.

The Republic of Congo also has a 50 kilometres (31 mi) belt of phosphate outcrops along the coast, with large deposits at Sintou Kola and Holle, 50 kilometers from Pointe Noire. Phosphate nodules, 110 kilometres (68 mi) west of Brazzaville, close to Comba, are believed to be of Neoproterozoic age.[6]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geology of the Republic of the Congo. |

- Schluter, Thomas (2006). Geological Atlas of Africa (PDF). Springer. pp. 84–85.

- Schluter 2006, p. 84.

- Kadima; et al. (2011). "Structure and geological history of the Congo Basin: an integrated interpretation of gravity, magnetic and reflection seismic data" (PDF). Basin Research.

- Kadima et. al. 2011, p. 499.

- "Hydrogeology of Republic of Congo". British Geological Survey.

- Schluter 2006, p. 86-87.