Geology of Cornwall

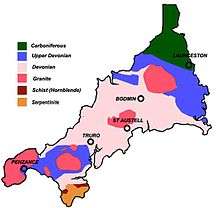

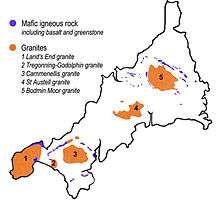

The geology of Cornwall, England, is dominated by its granite backbone, part of the Cornubian batholith, formed during the Variscan orogeny. Around this is an extensive metamorphic aureole (known locally as killas) formed in the mainly Devonian slates that make up most of the rest of the county. There is an area of sandstone and shale of Carboniferous age in the north east, and the Lizard peninsula is formed of a rare section of uplifted oceanic crust.

Coasts

Cornwall forms the tip of the south-west peninsula of the island Great Britain, and is therefore exposed to the full force of the prevailing winds that blow in from the Atlantic Ocean. The coastline is composed mainly of resistant rocks that give rise in many places to impressive cliffs.

The north and south coasts have different characteristics. The north coast is more exposed and therefore has a wilder nature. The prosaically-named High Cliff, between Boscastle and St Gennys, is the highest sheer-drop cliff in Cornwall at 735 ft (224 m). However, there are also many extensive stretches of fine golden sand which form the beaches that are so important to the tourist industry, such as those at St Ives, Hayle, Perranporth and Newquay. The only river estuary of any size on the north coast is that of the Camel, which provides Padstow with a safe harbour.

The south coast, dubbed the riviera, is somewhat more sheltered and there are several broad estuaries formed by drowned valleys or rias that offer safe anchorages to seafarers, such as at Falmouth and Fowey. Beaches on the south coast usually consist of coarser sand and shingle, interspersed with rocky sections of wave-cut platform. Raised beaches can be identified in various places these being geological evidence of past changes in sea levels.

Interior

The interior of the county consists of a roughly east–west spine of infertile and exposed upland, with a series of granite intrusions, such as Bodmin Moor, which contains the highest land within Cornwall. From east to west, and with approximately descending altitude, these are Bodmin Moor, the area north of St Austell (including St Austell Downs), the area south of Camborne and Redruth, and the Penwith or Land's End peninsula. These intrusions are the central part of the granite outcrops of south-west Britain, which include Dartmoor to the east in Devon and the Isles of Scilly to the west, the latter now being partially submerged.

The uplands are surrounded by more fertile, mainly pastoral farmland. Near the south coast, deep wooded valleys provide sheltered conditions for a flora that likes shade and a moist, mild climate. These areas are mainly of Devonian sandstone and slate.[1] The north east of Cornwall lies on Carboniferous rocks known as the Culm Measures. In places these have been subjected to severe folding, as can be seen on the north coast[2] near Crackington Haven, spectacularly at the Whaleback Pericline on the beach just south of Bude and at several other locations.

Granite

The intrusion of the granite into the surrounding sedimentary rocks[3] gave rise to extensive metamorphism and mineralisation,[4] and this led to Cornwall being one of the most important mining areas in Europe until the early 20th century. It is thought that tin ore (cassiterite) was exploited in Cornwall as early as the Bronze Age. Over the years, many other metals such as copper, lead, zinc and silver have all been mined in Cornwall.[5] Alteration of the granite also gave rise to extensive deposits of china clay (kaolinite), especially in the area to the north of St Austell, and this remains one of Cornwall's most important industries.

Granite was used as a building stone as early as the Bronze Age. Before the 17th century the granite was not quarried as it was far too difficult to cut the stone at that time. Builders used blocks lying about on the moors, known as moorstone, instead. By the later Middle Ages the masons were adept enough at dressing moorstone to use it in church building. Moorstone blocks were also used for bridging streams and for walls, stiles, posts and troughs.[6]

The Lizard peninsula

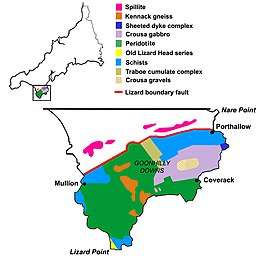

The Lizard complex is Britain's most complete [7] example of an ophiolite. Much of the peninsula consists of the dark green and red rock, serpentinite, which forms cliffs as at Kynance Cove, and can be carved and polished to create ornaments. This ultramafic rock forms a very infertile soil which covers the flat and marshy heaths of the Goonhilly Downs.

Mining and quarrying

Extraction of tin began in Cornwall in prehistoric times and continued until the late 20th century. Historically extensive tin and copper mining has occurred in Devon and Cornwall, as well as arsenic, silver, zinc and a few other metals. Granite, slate and aggregate are still quarried and china-clay extraction continues on a large scale. There are ample supplies of granite worth the cost of shipping out of the county and much Cornish granite has been used in distant places. It is one of the most appropriate materials for memorials and examples are found in most parts of Cornwall. As of 2007 there are no active metalliferous mines remaining. However, tin deposits still exist in Cornwall, and there is talk of reopening South Crofty tin mine.

Geological studies were made worthwhile due to the economic importance of mines and quarries: about forty distinct minerals have been identified from type localities in Cornwall, e. g. endellionite from St Endellion.

See also

References

- In the Tintagel and Camelford district the succession of strata is Tredorn phyllites, Trambley Cove beds, Volcanic series, Barras Nose beds, Woolgarden phyllites, Delabole slates, and Slaughterbridge beds (lowest); R. M. Barton (1964) An Introduction to the Geology of Cornwall. Truro: D. Bradford Barton; p. 89

- Enfield, M. A. [et al.] (1985) Structural and sedimentary evidence for the early tectonic history of the Bude and Crackington Formations, north Cornwall and Devon, Proceedings of the Ussher Society 6(2), 165-172.

- Henley, S. (1976) Rediscovery of a Granite Dyke at Perranporth, Cornwall, Transactions of the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall, XX(4), pp. 286-299

- Durrance, E. M. [et al.] (1982) Hydrothermal Circulation and Post-magmatic Changes in Granites of South-west England, Proceedings of the Ussher Society, 5(3), pp. 304-320

- Barton, D. B. (1963) A Guide to the Mines of West Cornwall. Truro: D. Bradford Barton, 52 pp.

- Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1970) "Building materials", in: Pevsner, N. Cornwall; 2nd ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin; pp. 29-34; p. 30

- Chandler, P. [et al.] (1984) A Gravity Survey of the Polyphant Ultrabasic Complex, East Cornwall, Proceedings of the Ussher Society 6(1), pp. 116-120

Bibliography

- Edmonds, E. A. [et al.] (1975) South-West England; based on previous editions by H. Dewey (British Geological Survey UK Regional Geology Guide series no. 17, 4th ed.) London: HMSO ISBN 0-11-880713-7

- Evans, C. D. R. & Hillis, R. R. (1990) Geology of the western English Channel and its western approaches (British Geological Survey UK Offshore Regional Report series, no. 9). London: HMSO ISBN 0-11-884475-X

- Hall, A. (2005) West Cornwall (Geologists' Association Guide series no. 13, 2nd ed.) London: Geologists' Association ISBN 0-900717-57-2

- Todd, A. C. & Laws, Peter (1972) The Industrial Archaeology of Cornwall. Newton Abbot: David & Charles

Further reading

- Bristow, C. M. (2004) Cornwall's Geology and Scenery

- English Heritage (2011) The Strategic Stone Study: a building stone atlas of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

- Selwood, E. B., Durrance, E. M. & Bristow, C. M. (eds.) (1998) The Geology of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly