Geology of Hertfordshire

The geology of Hertfordshire describes the rocks of the English county of Hertfordshire which are a northern part of the great shallow syncline known as the London Basin. The beds dip in a south-easterly direction towards the syncline's lowest point roughly under the River Thames. The most important formations are the Cretaceous chalks, which are exposed as the high ground in the north and west of the county, and the Cenozoic rocks made up of the Paleocene age Reading beds and Eocene age London Clay that occupies the remaining southern part.[1][2]

The Cretaceous

On the northern boundary and just inside the county, at the foot of the chalk Chiltern Hills, near Tring and Ashwell, there is a small strip of exposed Cretaceous Gault Clay and Upper Greensand. At 100 million years old, these are the oldest rocks in the county. Rocks get progressively younger as one moves in a south easterly direction through the county.[1][2]

The lowest layer of the chalk is the Chalk Marl, which, with the Totternhoe Clunch Stone above it, lies at the base of the Chiltern Hills escarpment. This is visible as a terrace projecting north-westwards, near Whipsnade and Ivinghoe.[1]

Above these beds, the Lower and Middle Chalk, without flints, rise up sharply to form the steepest part of the Dunstable Downs, which are the easterly continuation of the Chiltern Hills.[1][2]

Next comes the Chalk Rock, which, being a hard bed, caps the hilltops by Boxmoor, Apsley End and near Baldock. The Upper Chalk slopes southward towards the Paleogene boundary to the south.[1][2]

All the chalk was deposited between 100 million and 66 million years ago when the area was at the bottom of a shallow sea and some distance from the nearest land.[2]

The chalk is often covered by a clay-with-flints deposit, which is formed of the weathered remnants of Cenozoic rocks and chalk.[1][3]

The Cenozoic

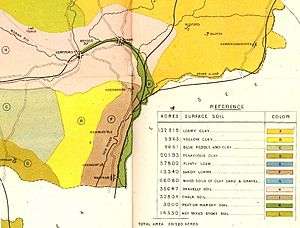

The Palaeocene Reading beds consist of mottled and yellow clays and sands, the latter are frequently hardened into masses made up of pebbles in a siliceous cement, known locally as Hertfordshire puddingstone. Examples of Reading Beds outliers occur in what are otherwise chalky areas at St Albans, Ayot Green, Burnham Green, Micklefield Green, Sarratt, and Bedmond. The Reading Beds were laid down about 60 million years ago when the area was a river estuary receiving river sediment from land to the west.[1][2]

The London Clay is a stiff, blue clay that weathers to brown and rests nearly everywhere upon the Reading beds. It represents the time 55 to 40 million years ago when Hertfordshire was once again under a deeper sea but was near enough to land to receive fine mud deposits.[1][2]

The Ice Age

About 478,000 to 424,000 years ago during the ice age period known as the Anglian Stage, glaciers approached from the North Sea and reached as far south-west as Bricket Wood. Glacial gravels and boulder clays cover a great deal of the whole area to the north east of the county and the Upper Chalk itself has been disturbed at Reed and Barley by glaciation.[1][2]

Prior to the ice ages the River Thames followed a path through the southern part of Hertfordshire, running from the area of modern Staines up the valley of the Colne to Hatfield and then eastward across Essex originally towards the primeval Rhine but later down the valley of the modern River Lea. This path was blocked by a mass of ice near Hatfield and a lake ponded up to the west of this around St Albans. Waters eventually overflowed near Staines to cut the path of the modern Thames through central London. When the ice retreated about 400,000 years ago the river bed along the new route followed the lower path and so the river remained on its present-day course. The flow in the Colne valley reversed, now flowing south as a tributary into the modern Thames. Superficial gravel deposits from the primordial Thames, are found throughout the Vale of St. Albans.[1][2]

At the retreat of the glaciers, wind blown powdered rock known as loess was deposited over the whole county, forming thin layers under a metre thick. This reddish clay is easily formed into bricks at the lowish temperatures attainable in a wood fired kiln and gained the name brickearth. It gave rise to rural brick making industries scattered throughout the county. It also makes for fine, easily cultivated and fertile soils.[2][3]

See also

- Hertfordshire for a general description of the county.

- Geology of the United Kingdom

- Geology of England

- Woolwich-and-Reading Beds

Notes

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 398.

- Hertfordshire Geological Society

- Dacorum Landscape Character Assessment 2002

References

- Hertfordshire at Natural England . Direct.gov.uk, 2008-11-20.

- Hertfordshire Geological Society - Containing maps and cross section.

- "Dacorum Landscape Character Assessment" (PDF). Countryside Commission / English Nature. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2009-03-02. Describing landscape and soil types.

- Asymmetrical Valleys of the Chiltern Hills C. D. Ollier and A. J. Thomasson, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 123, No. 1 (March 1957), pp. 71–80 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers

- Hertfordshire RIGS Group, Herts County Council (2003). "A Geological Conservation Strategy for Hertfordshire" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-09-18. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)