Gatchina Palace

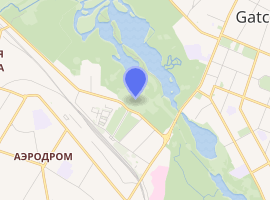

The Great Gatchina Palace (Russian: Большой Гатчинский дворец) is a palace in Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It was built from 1766 to 1781 by Antonio Rinaldi for Count Grigori Grigoryevich Orlov, who was a favourite of Catherine the Great, in Gatchina, a suburb of the royal capital Saint Petersburg. The Gatchina Palace combines classical architecture and themes of a medieval castle with ornate interiors typical of Russian classicism, located on a hill in central Gatchina next to Lake Serebryany. The Gatchina Palace became one of the favourite residences of the Russian Imperial Family, and during the 19th century was an important site of Russian politics. Since the February Revolution in 1917 it has been a museum and public park, and received UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 1990.[1]

| Great Gatchina Palace | |

|---|---|

Большой Гатчинский дворец | |

Southern facade of the palace | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Classical |

| Location | Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia |

| Coordinates | 59°33′48″N 30°6′27″E |

| Construction started | 1766 |

| Completed | 1781 |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 540 |

| Inscription | 1990 (14th session) |

| Area | 3,934.1 ha (9,721 acres) |

History

Imperial era

In 1765, Catherine the Great, the Empress of the Russian Empire, purchased from Prince Boris Kurakin the Gatchina Manor, a small manor 40 kilometers (25 mi) south of the royal capital of Saint Petersburg. Catherine presented the manor to Count Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov, who had reportedly organized the assassination of Tsar Peter III three years earlier, resulting in her becoming empress. Orlov was a favorite of Catherine's, and Gatchina Manor was gifted to him as gratitude for his role in the coup d'etat. On 30 May 1766, construction of a new palace in the Classical architecture style began on a hill next to Lake Serebryany on the grounds of Gatchina Manor. Catherine and Orlov commissioned the new palace to be designed by Antonio Rinaldi, an architect from Italy who was particularly popular in Russia at the time. Rinaldi's design contained Russian architectural features combined with those of a medieval castle and an English hunting castle. The palace was to be lined with special stone mined in villages near to Gatchina, including parik limestone mined in Paritsy for the main exterior of the buildings, and pudost stone from Pudost for the vestibule and the parapet above the cornice. Gatchina Palace became the first palace to be located in Saint Petersburg's suburbs, as large estates were typically built within a short distance of the city center. Construction was slow, with the main structure only being completed by the end of 1768 and work on the exterior decoration not being completed until 1772, with the interior delayed further into the late 1770s. The Great Gatchina Palace was finally completed in 1781, almost 15 years after construction began, and Orlov died only two years later in 1783.

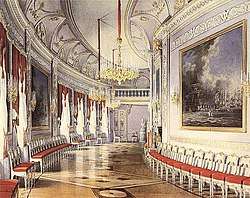

Following Orlov's death, Catherine took such a great liking to Gatchina Palace and its accompanying park that she bought it from his heirs. She presented it to her son, Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich (the future Tsar Paul I), despite already building him a home, Pavlovsk Palace, in Saint Petersburg. During the years before coming to the throne, Paul limited his remaining budget on investing in building the town of Gatchina around his new palace, and used his experience from his travels around Europe to make it an exemplary palace and town. In the 1790s Paul expanded and rebuilt much of the palace, commissioning Vincenzo Brenna and Andrei Zakharov with the renovations. The interiors were redone in the Neoclassical style, numerous additions were added to the park such as bridges, gates, and pavilions, naming areas of the park "The Isle of Love", "The Private garden", "The Holland garden" and "The Labyrinth". In 1796, after the death of his mother, Paul became Tsar Paul I of Russia, and granted Gatchina the status of Imperial City, a designation for the official residences of the Russian monarchs. After the death of Paul in 1801, Gatchina Palace came into the ownership of his wife Maria Feodorovna, who in 1809 requested the architect Andrei Nikiforovich Voronikhin make small alterations in the palace to adapt it "in case of winter stay". In 1835, a signal optical telegraph was installed on one of the towers.

In the 1840s, Gatchina Palace was now in the ownership of Tsar Nicholas I, who initiated major reconstruction works of the palace, particularly of its grounds. Roman Ivanovich Kuzmin, the chief architect of the Ministry of the Imperial Court, led the project centred on the palace's main square, which was completely torn up, raised in height, had basement levels added underneath, and decoration remodelled. The adjoining buildings were also raised in height by one storey, and because the main building no longer dominated the palace Kuzmin had its towers raised an extra storey. A new canopy was added to the balcony overlooking the parade grounds, which was intended to be made from marble but was later made from cast iron instead. Dilapidated bastions and retaining walls around the palace were demolished and rebuilt.

On 1 August 1850, a monument to Tsar Paul I was erected at the parade grounds. Another was later built at the Priory Palace, miniature palace on the shore of the Black Lake (the smaller southern lake of Lake Serebryany) constructed for the Russian Grand Priory of the Order of St John by a decree of Paul I dated 23 August 1799.[2]

In 1854, a railroad connecting Gatchina and Saint Petersburg was opened, and the territory of Gatchina was expanded with several villages in the vicinity being incorporated into the city.[3] The following year Gatchina Palace came under the ownership of Tsar Alexander II, who used it as his second residence. Alexander built a hunting village and other additions for his imperial hunting crew, and turned the area south of Gatchina into a retreat where he and his guests could enjoy the unspoiled wilderness of northwestern Russia. Alexander II also made updates and renovations in the main Gatchina Palace until his assassination in Saint Petersburg in 1881. Gatchina Palace was passed to his shaken son, the new Tsar Alexander III, who was advised that he and his family would be safer at the palace as opposed to at the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, and became known as "The Citadel of Autocracy" after the Tsar's reactionary policies. Alexander III spent most of his time living in Gatchina Palace, where he signed decrees, held diplomatic receptions, theatrical performances, masquerades and costumed balls, and other events and entertainment. Alexander III introduced technological modernizations to Gatchina Palace, such as indoor heaters, electric lights, a telephone network, non-freezing water pipes and a modern sewage system. His son, the future Tsar Nicholas II, spent his youth in the Gatchina Palace, although he and his family would make Tsarskoye Selo his home. His mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, widow of Alexander III, was the patron of the city of Gatchina, the palace and its parks.

Russian Civil War

In the early 20th century, increasing instability in Russia led to the February Revolution of 1917, resulting in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the establishment of the Provisional Government headed by Alexander Kerensky. The abdication meant Gatchina Palace ceased to belong to the royal family and became state property, and on the decision of the new government on 27 May 1917, commissions for the acceptance and inventory of palaces. The Gatchina commission was led by Valentin Platonovich Zubov, a prominent art critic and founder of the Russian Institute of Art History, who eventually converted the palace into a museum and became its first director. Following the October Revolution and the subsequent outbreak of the Russian Civil War, the Gatchina Palace served as a local headquarters for troops loyal to the White Movement. Alexander Kerensky visited the palace on 27 October 1917, when fighting broke out in Gatchina between Cossack units of General Pyotr Krasnov and detachments of the Red Guards, but avoided the palace. On 1 November, the victorious Reds held a rally outside the palace in the main square, where Pavel Yefimovich Dybenko persuaded the Cossack units stationed not to oppose the Red authorities in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) and to surrender. Kerensky left Gatchina Palace that night, which was occupied by Red troops the following day, and the museum was later opened on 19 May 1918. Gatchina Palace was the site of fighting in 1919, when White Army troops led by Nikolai Yudenich entered Gatchina in an attempt to take the town from the Red Army. The White forces were defeated, and Red soldiers who died in the battle were buried in the parade grounds.

Soviet era

After the Russian Civil War ended in Soviet Russian victory, the Gatchina Palace returned to its function as a museum. The data on attendance in the first years after its opening showed it was visited by the largest number of visitors, with more than 21,000 visitors in 1921. In 1926, Gatchina Palace was stripped of all unnecessary items, such as furniture, bronze products and carpets, to be sold to make money for the Soviet state. It was largest of the palaces-museums in the suburbs of Petrograd and was often called the "Suburban Hermitage".

In 1941, the Soviet Union's entry into World War II following the German invasion saw the museum at Gatchina Palace evacuated to protect the building and valuables from aerial bombardment. On 15 August 1941, a bomb dropped by the Luftwaffe exploded next to the palace, and by the end of the month the city was within reach of German artillery. On 24 August, shells damaged the square, and on 3 September, an air bomb caused considerable damage to the courtyard. It was not possible to carry out the complete evacuation of the valuables in the palace, with only four echelons with the most valuable exhibits sent east and one echelon was sent to Leningrad (Saint Petersburg). The remaining property was located in the basement of the palace, part of a large sculpture was buried in the park, and the others stored in an area closed with sandbags. On 9 September, the remaining staff of the museum were evacuated, and on the same day a tower was damaged by a shell, while another shell exploded in the park near the palace. Gatchina Palace was subsequently occupied by the Wehrmacht until January 1944, when it was abandoned during the German retreat. They set fire to the palace, destroying the historic interior and gutting parts of palace, and stole some of the remaining valuables. A German soldier left graffiti on a wall with the inscription "We were here. We will not return here. If Ivan comes, everything will be empty".

When Gatchina was retaken by the Red Army, the palace's remains were protected with temporary shields until basic restoration work could begin in 1948. The return of the museum was not planned because it was considered unprofitable, and saved items from the collections were transferred by order of the Ministry of Culture of the USSR and the RSFSR for storage in 24 museums across the country. From 1950 to 1959, Gatchina Palace housed a branch of the Naval Academy of the USSR, and then the All-Union Research Institute. In 1960, the building of the palace was removed from the account of the GIOP, the authority for historical and cultural monuments in the Leningrad area, but this status was restored in the 1970s. In 1961, the architect Mikhail Plotnikov initiated the development of a project to restore the Gatchina Palace, including taking architectural measurements and searching archival materials. Interior design drawings were made for the first and second floors, with the restoration of the interiors pinned to their state in 1890. The restored Gatchina Palace was not intended to become a museum again, but to be used permanently by the All-Union Research Institute. Despite the research, Plotnikov's plan was ultimately not implemented, and cancelled in 1963.

The museum was eventually reopened in the palace alongside the All-Union Research Institute, and restoration of the building was resumed thanks to the efforts of A. S. Yolkina, the main curator from 1968 to 1998. For 8 years, Yolkina appealed officials of different levels for a restoration, and the All-Union Research Institute relinquished use of the building. In 1976, Mikhail Plotnikov was invited to restore Gatchina Palace again, and developed a new project for the restoration of the main halls (the second floor of the main building) to their state at the end of the 18th century, the period of the palace's prime. Restoration of the stucco decoration was conducted by sculptor-modeler L. A. Strizhova, and painting works were performed by a team of restorers under the direction of Yakov Kazakov, a member of the Leningrad Union of Artists and winner of the Lenin Prize. The first interiors of the palace were opened for viewing on 8 May 1985, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of victory in World War II. Funds allocated for the restoration of the palace were minimal following perestroika and work slowed. In 1990, Gatchina Palace and its grounds received UNESCO World Heritage Site status as part of numerous historic sites in the Saint Petersburg area.[1]

Russian era

The dissolution of the Soviet Union meant that funds for the restoration continued to be minimal until 2006, when the Russian government significantly increased funds. The full restoration of the palace and park was planned by 2012, however, due to the economic issues the financing was postponed and restoration work has again slowed. Gatchina Palace became a popular filming location in cinema, particularly for period dramas, including Poor Poor Paul and War & Peace.

Gallery

Panorama of the Great Gatchina Palace's southern facade in 2010

Panorama of the Great Gatchina Palace's southern facade in 2010 Aerial photo of Great Gatchina Palace's northern facade with Gatchina in the background

Aerial photo of Great Gatchina Palace's northern facade with Gatchina in the background

See also

References

- "Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- a small Priory Palace

- Suburbs of St.Petersburg : Gatchina Archived 17 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gatchina Palace. |