Gallipoli

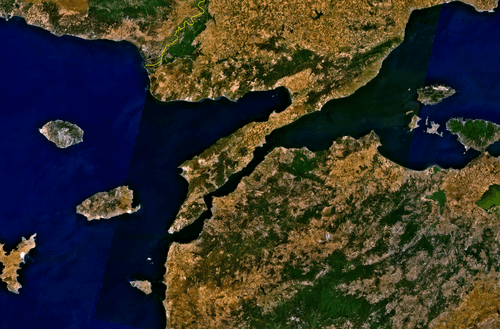

The Gallipoli peninsula (/ɡəˈlɪpəli, ɡæ-/;[1] Turkish: Gelibolu Yarımadası; Greek: Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, Chersónisos tis Kallípolis) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name "Καλλίπολις" (Kallípolis), meaning "Beautiful City",[2] the original name of the modern town of Gelibolu. In antiquity, the peninsula was known as the Thracian Chersonese (Greek: Θρακική Χερσόνησος, Thrakiké Chersónesos; Latin: Chersonesus Thracica).

The peninsula runs in a south-westerly direction into the Aegean Sea, between the Dardanelles (formerly known as the Hellespont), and the Gulf of Saros (formerly the bay of Melas). In antiquity, it was protected by the Long Wall,[3][4][5][6] a defensive structure built across the narrowest part of the peninsula near the ancient city of Agora. The isthmus traversed by the wall was only 36 stadia in breadth[7] (about 6.5 km), but the length of the peninsula from this wall to its southern extremity, Cape Mastusia, was 420 stadia[7] (about 77.5 km).

History

Antiquity and Middle Ages

In ancient times, the Gallipoli Peninsula was known as the Thracian Chersonesus (from Greek χερσόνησος, "peninsula"[8]) to the Greeks and later the Romans. It was the location of several prominent towns, including Cardia, Pactya, Callipolis (Gallipoli), Alopeconnesus (Greek: Ἀλωπεκόννησος),[9] Sestos, Madytos, and Elaeus. The peninsula was renowned for its wheat. It also benefited from its strategic importance on the main route between Europe and Asia, as well as from its control of the shipping route from Crimea. The city of Sestos was the main crossing-point on the Hellespont.

According to Herodotus, the Thracian tribe of Dolonci (Greek: Δόλογκοι) (or "barbarians" according to Cornelius Nepos) held possession of Chersonesus before the Greek colonization. Then, settlers from Ancient Greece, mainly of Ionian and Aeolian stock, founded about 12 cities on the peninsula in the 7th century BC.[10] The Athenian statesman Miltiades the Elder founded a major Athenian colony there around 560 BC. He took authority over the entire peninsula, building up its defences against incursions from the mainland. It eventually passed to his nephew, the more famous Miltiades the Younger, around 524 BC. The peninsula was abandoned to the Persians in 493 BC after the outbreak of the Greco-Persian Wars (499–478 BC).

The Persians were eventually expelled, after which the peninsula was for a time ruled over by Athens, which enrolled it into the Delian League in 478 BC. The Athenians established a number of cleruchies on the Thracian Chersonese and sent an additional 1,000 settlers around 448 BC. Sparta gained control after the decisive battle of Aegospotami in 404 BC, but the peninsula subsequently reverted to the Athenians. In the 4th century BC, the Thracian Chersonese became the focus of a bitter territorial dispute between Athens and Macedon, whose king Philip II sought possession. It was eventually ceded to Philip in 338 BC.

After the death of Philip's son Alexander the Great in 323 BC, the Thracian Chersonese became the object of contention among Alexander's successors. Lysimachus established his capital Lysimachia here. In 278 BC, Celtic tribes from Galatia in Asia Minor settled in the area. In 196 BC, the Seleucid king Antiochus III seized the peninsula. This alarmed the Greeks and prompted them to seek the aid of the Romans, who conquered the Thracian Chersonese, which they gave to their ally Eumenes II of Pergamon in 188 BC. At the extinction of the Attalid dynasty in 133 BC it passed again to the Romans, who from 129 BC administered it in the Roman province of Asia. It was subsequently made a state-owned territory (ager publicus) and during the reign of the emperor Augustus it was imperial property.

The Thracian Chersonese was part of the Eastern Roman Empire from its foundation in 330 AD. In 443 AD, Attila the Hun invaded the Gallipoli Peninsula during one of the last stages of his grand campaign that year. He captured both Callipolis and Sestus.[11] Aside from a brief period from 1204 to 1235, when it was controlled by the Republic of Venice, the Byzantine Empire ruled the territory until 1356. During the night between 1 and 2 March 1354, a strong earthquake destroyed the city of Gallipoli and its city walls, weakening its defenses.

Ottoman era

Ottoman conquest

Within a month after the devastating 1354 earthquake the Ottomans besieged and captured the town of Gallipoli, making it the first Ottoman stronghold in Europe and the staging area for Ottoman expansion across the Balkans.[12] The Savoyard Crusade recaptured Gallipoli for Byzantium in 1366, but the beleaguered Byzantines were forced to hand it back in September 1376. The Greeks living there were allowed to continue their everyday activities. In the 19th century, Gallipoli (Turkish: Gelibolu) was a district (kaymakamlik) in the Vilayet of Adrianople, with about thirty thousand inhabitants: comprising Greeks, Turks, Armenians and Jews.[13]

Crimean War (1853–1856)

Gallipoli became a major encampment for British and French forces in 1854 during the Crimean War, and the harbour was also a stopping-off point between the western Mediterranean and Istanbul (formerly Constantinople.[14][15])

In March 1854 British and French engineers constructed an 11.5 km line of defence to protect the peninsula from a possible Russian attack and so secure control of the route to the Mediterranean Sea.[16]:414

First Balkan War, persecution of Greeks (1912–1913)

Gallipoli did not experience any more wars until the First Balkan War, when the 1913 Battle of Bulair and several minor skirmishes took place there. A dispatch on 7 July 1913 reported that Ottoman troops treated Gallipoli's Greeks "with marked depravity" as they "destroyed, looted, and burned all the Greek villages near Gallipoli". Ottoman forces sacked and completely destroyed many villages and killed some Greeks. The cause of this savagery in the part of the Turks was their fear that if Thrace was declared autonomous the Greek population might be found numerically superior to the Muslims.

The Turkish Government, under the pretext that a village was within the firing line, ordered its evacuation within three hours. The residents abandoned everything they possessed, left their village and went to Gallipoli. Seven of the Greek villagers who stayed two minutes later than the three-hour limit allowed for the evacuation were shot by the soldiers. After the end of the Balkan War the exiles were allowed to return. But as the Government allowed only the Turks to rebuild their houses and furnish them, the exiled Greeks were compelled to remain in Gallipoli.[17]

World War I: Gallipoli Campaign, persecution of Greeks (1914–1919)

.jpg)

.jpg)

During World War I (1914-1918), French, British and colonial forces (Australian, New Zealand, Newfoundland, Irish and Indian) fought the Gallipoli campaign (1915-1916) in and near the peninsula, seeking to secure a sea route to relieve their eastern ally, Russia. The Ottomans set up defensive fortifications along the peninsula and contained the invading forces.

In early 1915, attempting to seize a strategic advantage in World War I by capturing Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), the British authorised an attack on the peninsula by French, British and British Empire forces. The first Australian troops landed at ANZAC Cove early in the morning of 25 April 1915. After eight months of heavy fighting the last Allied soldiers withdrew by 9 January 1916.

The campaign, one of the greatest Ottoman victories during the war, is considered by historians as a major Allied failure. Turks regard it as a defining moment in their nation's history: a final surge in the defence of the motherland as the Ottoman Empire crumbled. The struggle formed the basis for the Turkish War of Independence and the founding of the Republic of Turkey eight years later under President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who first rose to prominence as a commander at Gallipoli.

The Ottoman Empire instituted the Gallipoli Star as a military decoration in 1915 and awarded it throughout the rest of World War I.

The campaign was the first major military action of Australia and New Zealand (or Anzacs) as independent dominions, and is often considered to mark the birth of national consciousness in those nations. The date of the landing, 25 April, is known as "Anzac Day". It remains the most significant commemoration of military casualties and "returned soldiers" in Australia and New Zealand.

On the Allied side one of the promoters of the expedition was Britain's First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, whose bullish optimism hurt his reputation that took years to recover: the English had the popular belief that there were more British and French casualties and deaths than among their Anzac comrades; Australians and New Zealanders resented perceived British incompetence and the alleged British propensity to use them wastefully as cannon fodder. No serious attempt was made to understand the nature of the terrain nor logistical support required for success against the Turkish army. The wishful thinking of generals not based on reality doomed the campaign before it began. Hart, Peter (2011). Gallipoli. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199361274.

Prior to the Allied landings in April 1915,[18] the Ottoman Empire deported Greek residents from Gallipoli and surrounding region and from the islands in the sea of Marmara, to the interior where they were at the mercy of hostile Turks.[19] The Greeks had little time to pack and the Ottoman authorities permitted them to take only some bedding and the rest was handed over to the Government.[19] The Turks also plundered Greek houses and properties.[20] A testimony of a deportee described how the deportees were forced onto crowded steamers, standing-room only; how, on disembarking, men of military age were removed (for forced labour in the labour battalions of the Ottoman army) and how the rest were "scattered… among the farms like ownerless cattle".

The Metropolitan of Gallipoli wrote on 17 July 1915 that the extermination of the Christian refugees was methodical.[17] He also mentions that "The Turks, like beasts of prey, immediately plundered all the Christians' property and carried it off. The inhabitants and refugees of my district are entirely without shelter, awaiting to be sent no one knows where ...".[17] Many Greeks died from hunger and there were frequent cases of rape among women and young girls, as well as their forced conversion to Islam.[17]

Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

Greek troops occupied Gallipoli on 4 August 1920 during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–22, considered part of the Turkish War of Independence. After the Armistice of Mudros of 30 October 1918 it became a Greek prefecture centre as "Kallipolis". However, Greece was forced to withdraw from Eastern Thrace after the Armistice of Mudanya of October 1922. Gallipoli was briefly handed over to British troops on 20 October 1922, but finally returned to Turkish rule on 26 November 1922.

In 1920, after the defeat of the Russian White army of General Pyotr Wrangel, a significant number of émigré soldiers and their families evacuated to Gallipoli from the Crimean Peninsula. From there, many went to European countries, such as Yugoslavia, where they found refuge.

There are now many cemeteries and war memorials on the Gallipoli peninsula.

Turkish Republic

Between 1923 and 1926 Gallipoli became the centre of Gelibolu Province, comprising the districts of Gelibolu, Eceabat, Keşan and Şarköy. After the dissolution of the province, it became a district centre in Çanakkale Province.

Notable people

- Ahmed Bican (1398–ca. 1466), author

- Piri Reis (1465/70–1553[21]), admiral, geographer and cartographer

- Mustafa Âlî (1541–1600), Ottoman historian, politician and writer

- Sofia Vembo (1910–1978), Greek singer and actress

References

- Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- Καλλίπολις, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Xenophon (January 1921). Hellenica, Volume II. Translated by Brownson, Carleton L. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674990999.

- Siculus, Diodorus (January 1933). Library of History, Volume I. Translated by Oldfather, Charles H. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674993075.

- Secundus, Gaius Plinius (1855). Bostock, John; Riley, Henry Thomas (eds.). The Natural History. London: H. G. Bohn.

- Plutarch (January 1919). Lives (in Ancient Greek). Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674991101.

- Herodotus, The Histories, vi. 36; Xenophon, ibid.; Pseudo-Scylax, Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, 67 (PDF)

- Xερσόνησος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- "Alopeconnesus". wikimapia.org.

- Herodotus, vi. 34; Cornelius Nepos, Lives of Eminent Commanders, "Miltiades", 1

- Attila the Hun: Barbarian Terror and the Fall of the Roman Empire. Vintage. 2011. p. 105. ISBN 978-1844139156.

- Crowley, Roger. 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West. New York: Hyperion, 2005. p 31 ISBN 1-4013-0850-3.

-

- "Crimea". Archived from the original on 22 February 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- "Charles Usherwood's Service Journal, 1852 – 1856: despatch". victorianweb.org.

- Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey, 1914–1918. Constantinople [London, Printed by the Hesperia Press]. 1919.

- The Berlin-Baghdad Express-p.251

- Lieberman, Benjamin (December 2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1442223196.

- The Meaning of Gallipoli to Hellenism

- "Ana Sayfa" (PDF).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gallipoli (Turkey). |