FRELIMO

The Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) (Portuguese pronunciation: [fɾeˈlimu]), from the Portuguese Frente de Libertação de Moçambique is the dominant political party in Mozambique. Founded in 1962, FRELIMO began as a nationalist movement fighting for the independence of the Portuguese Overseas Province of Mozambique. Independence was achieved in June 1975 after the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon the previous year. At the party's 3rd Congress in February 1977, it became an officially Marxist–Leninist political party. It identified as the Frelimo Party (Partido Frelimo).[5]

Mozambique Liberation Front Frente de Libertação de Moçambique | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | FRELIMO |

| Leader | Filipe Nyusi |

| Secretary-General | Roque Silva Samuel |

| Founder | Eduardo Mondlane Samora Machel |

| Founded | 25 June 1962 |

| Merger of | MANU, UDENAMO and UNAMI |

| Headquarters | Dar es Salaam (1962–75)[1] Maputo (1975–present) |

| Youth wing | Mozambican Youth Organisation |

| Women's wing | Mozambican Women Organisation |

| Veteran's League | Association of Combatants of the National Liberation Struggle |

| Ideology | Democratic socialism[2] Marxism–Leninism (1977–89)[3] |

| Political position | Centre-left to left-wing |

| International affiliation | Socialist International |

| African affiliation | Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | Unity, Criticism, Unity[4] |

| Assembly of the Republic | 184 / 250

|

| SADC PF | 0 / 5

|

| Pan-African Parliament | 0 / 5

|

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Frelimo Party has ruled Mozambique since then, first as a one-party state. It struggled through a long civil war (1976–1992) against an anti-Communist faction known as Mozambican National Resistance or RENAMO. The insurgents from RENAMO received support from the then white-minority governments of Rhodesia and South Africa. The Frelimo Party approved a new constitution in 1990, which established a multi-party system. Since democratic elections in 1994 and subsequent cycles, it has been elected as the majority party in the parliament of Mozambique.

Independence war (1964–1974)

After World War II, while many European nations were granting independence to their colonies, Portugal, under the Estado Novo regime, maintained that Mozambique and other Portuguese possessions were overseas territories of the metropole (mother country). Emigration to the colonies soared. Calls for Mozambican independence developed rapidly, and in 1962 several anti-colonial political groups formed FRELIMO. In September 1964, it initiated an armed campaign against Portuguese colonial rule. Portugal had ruled Mozambique for more than four hundred years; not all Mozambicans desired independence, and fewer still sought change through armed revolution.

FRELIMO was founded in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika on 25 June 1962, when three regionally based nationalist organizations: the Mozambican African National Union (MANU), National Democratic Union of Mozambique (UDENAMO), and the National African Union of Independent Mozambique (UNAMI,) merged into one broad-based guerrilla movement. Under the leadership of Eduardo Mondlane, elected president of the newly formed Mozambican Liberation Front, FRELIMO settled its headquarters in 1963 in Dar es Salaam. Uria Simango was its first vice-president.

The movement could not then be based in Mozambique as the Portuguese opposed nationalist movements and the colony was controlled by the police. (The three founding groups had also operated as exiles.) Tanzania and its president, Julius Nyerere, were sympathetic to the Mozambican nationalist groups. Convinced by recent events, such as the Mueda massacre, that peaceful agitation would not bring about independence, FRELIMO contemplated the possibility of armed struggle from the outset. It launched its first offensive in September 1964.

During the ensuing war of independence, FRELIMO received support from China, the Soviet Union, the Scandinavian countries, and some non-governmental organisations in the West. Its initial military operations were in the North of the country; by the late 1960s it had established "liberated zones" in Northern Mozambique in which it, rather than the Portuguese, constituted the civil authority. In administering these zones, FRELIMO worked to improve the lot of the peasantry in order to receive their support. It freed them from subjugation to landlords and Portuguese-appointed "chiefs", and established cooperative forms of agriculture. It also greatly increased peasant access to education and health care. Often FRELIMO soldiers were assigned to medical assistance projects.

Its members' practical experiences in the liberated zones resulted in the FRELIMO leadership increasingly moving toward a Marxist policy. FRELIMO came to regard economic exploitation by Western capital as the principal enemy of the common Mozambican people, not the Portuguese as such, and not Europeans in general. Although it was an African nationalist party, it adopted a non-racial stance. Numerous whites and mulattoes were members.

The early years of the party, during which its Marxist direction evolved, were times of internal turmoil. Mondlane, along with Marcelino dos Santos, Samora Machel, Joaquim Chissano and a majority of the Party's Central Committee promoted the struggle not just for independence but to create a socialist society. The Second Party Congress, held in July 1968, approved the socialist goals. Mondlane was reelected party President and Uria Simango was re-elected vice-president.

After Mondlane's assassination in February 1969, Uria Simango took over the leadership, but his presidency was disputed. In April 1969, leadership was assumed by a triumvirate, with Machel and Marcelino dos Santos supplementing Simango. After several months, in November 1969, Machel and dos Santos ousted Simango from FRELIMO. Simango left FRELIMO and joined the small Revolutionary Committee of Mozambique (COREMO) liberation movement.

FRELIMO established some "liberated" zones (countryside zones with native rural populations controlled by FRELIMO guerrillas) in Northern Mozambique. The movement grew in strength during the ensuing decade. As FRELIMO's political campaign gained coherence, its forces advanced militarily, controlling one-third of the area of Mozambique by 1969, mostly in the northern and central provinces. It was not able to gain control of the cities located inside the "liberated" zones but established itself firmly in the rural regions.

In 1970 the guerrilla movement suffered heavy losses as Portugal launched its ambitious Gordian Knot Operation (Operação Nó Górdio), which was masterminded by General Kaúlza de Arriaga of the Portuguese Army. By the early 1970s, FRELIMO's 7,000-strong guerrilla force had opened new fronts in central and northern Mozambique. It was engaging a Portuguese force of approximately 60,000 soldiers in over 4 provinces.

The April 1974 "Carnation Revolution" in Portugal overthrew the Portuguese Estado Novo regime, and the country turned against supporting the long and draining colonial war in Mozambique, Angola and Guinea-Bissau. Portugal and FRELIMO negotiated Mozambique's independence, which resulted in a transitional government until official independence from Portugal in June 1975.

FRELIMO established a one-party state based on socialist principles, with Samora Machel re-elected as President of FRELIMO and subsequently the First President of the People's Republic of Mozambique. The new government first received diplomatic recognition, economic and military support from Cuba and the Socialist Bloc countries. Marcelino dos Santos became vice-president of FRELIMO and the central committee was expanded.[6]

At the same time FRELIMO had to deal with various small political parties that sprung up and were now contesting for control of Mozambique with FRELIMO along with the reaction of white settlers. Prominent groups included FICO ("I stay" in Portuguese) and the "Dragons of Death" which directly clashed with FRELIMO.[7] Government forces moved in and quickly smashed these movements and arrested various FRELIMO dissidents and Portuguese collaborators who were involved in FICO, the Dragons and other political entities that conspired or aligned against FRELIMO. These included prominent dissidents such as Uria Simango, his wife Celina, Paulo Gumane and outright traitors like Lazaro Nkavandame and Adelino Gwambe.[8]

Socialist period (1975–1989)

Mozambique's national anthem from 1975 to 1992 was "Viva, Viva a FRELIMO" (English: "Long Live FRELIMO").

Immediately after independence, Mozambique and FRELIMO faced extraordinarily tough circumstances. The country was bankrupt with almost all of its skilled workforce fleeing or already fled, a 95% illiteracy rate[9] and a brewing counter revolutionary movement known as the "Mozambique National Resistance" was beginning its first strikes against key government infrastructure with the assistance of Ian Smith's Rhodesia.[10] As RENAMO grew in strength and started directly terrorising the population, FRELIMO and RENAMO began clashing directly in what would quickly turn into the deadly Mozambican Civil War which did not end until 1992.

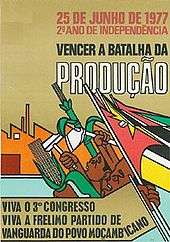

Large steps had already been taken towards the construction of a Mozambican socialist society by time of the 3rd Congress in 1977, including the nationalisation of the land, many agricultural, industrial and commercial enterprises, rented housing, the banks, health and education. FRELIMO transformed itself into a Marxist-Leninist Vanguard Party of the worker-peasant alliance at the 3rd Congress of FRELIMO in February 1977. The Congress laid down firmly that the political and economic guidelines for the development of the economy and the society would be for the benefit of all Mozambicans.[11] FRELIMO was also restructured extensively, the central committee expanding to over 200 members and the transformation of FRELIMO from a front into a formal political party, adopting the name "Partido FRELIMO" (FRELIMO Party).[12]

FRELIMO begun extensive programs for economic development, healthcare and education. Healthcare and Education became free and universal to all Mozambicans and the government begun a mass program of immunisations which was praised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as one of the most successful ever initiated in Africa. The scheme reached over 90% of the Mozambican Population in the first five years and led to a 20% drop in infant mortality rates.[13][14] Illiteracy rates dropped from 95% in 1975 to 73% in 1978.

Despite the difficult situation and economic chaos the Mozambican economy grew appreciably from the period of 1977–1983.[15]

However, some serious setbacks occurred, with particular force in the years 1982–1984. Neighbouring states, firstly Rhodesia and then South Africa, made direct armed incursions and promoted the growing RENAMO insurgency which continued to carry out economic sabotage and terrorism against the population.[16] Natural disasters compounded the already devastating situation, with large scale floods in some regions from Tropical Storm Domoina in 1984, followed by extensive droughts.[17]

Some of FRELIMO's more ambitious policies also caused further stress to the economy. Particularly FRELIMO's agricultural policy from 1977-1983 which placed heavy emphasis on state farms and neglected smaller peasant and community farms caused discontent among many peasant farmers and led to a reduction in production.[18] At the 4th Party Congress in 1984 FRELIMO acknowledged its mistakes in the economic field and adopted a new set of directives and plans,[15] reversing their previous positions and promoting more peasant and communal based farming projects over the larger state farms, many of which were either dismantled or shrunk.[19]

As the war with South-African backed RENAMO intensified much of the precious gains to healthcare, education and basic infrastructure by FRELIMO was wiped out.[20] Agriculture fell into disarray as farms were burnt and farmers fled into the cities for safety, industrial production slowed as many workers were conscripted into battle against RENAMO bandits and frequent raids against key roads and railways caused economic chaos across the country.[21] FRELIMO's focus rapidly shifted from socialist construction to maintaining a basic level of infrastructure and protecting the towns and cities as best they could. Despite small scale reforms in the party and state and the growing war Machel continued to maintain a hardline Marxist–Leninist stance and refused to negotiate with RENAMO.

In 1986 while returning from a meeting with Zaire and Malawi, President Samora Machel died in a suspicious airplane crash many blamed on the apartheid regime in Pretoria. In the immediate aftermath the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of FRELIMO assumed the duties of President of FRELIMO and President of Mozambique until a successor could be elected.[22] Joaquim Alberto Chissano was elected as the President of FRELIMO and was inaugurated as the Second President of the People's Republic of Mozambique on 6 November 1986. Despite being considered a "Moderate Marxist"[23] Chissano initially maintained Machel's hardline stance against RENAMO but begun economic reforms with the adoption of The World Bank and IMF's "Economic Rehabilitation Program" (ERP) in September 1987.[24] By 1988 Chissano had relented on his hardliner position and begun seeking third party negotiations with RENAMO to end the conflict.

In 1989 at the 5th Party Congress, FRELIMO officially dropped all references to Marxism–Leninism and class struggle from its party directives and documents[25] and instead Democratic Socialism was adopted the official ideology of FRELIMO while talks continued with RENAMO to broker a ceasefire.[26]

Marxism to social democracy (1989-2000)

With the removal of the final vestiges of Marxism from FRELIMO at the 5th Congress greater economic reform programs commenced with the help of the World Bank, IMF and various international donors. FRELIMO also believed it needed to reduce all traces of socialist influence, this resulted in the removal of hardline Marxists such as Sergio Viera, Jorge Rebelo and Marcelino dos Santos from positions of power and influence within the party. Additionally FRELIMO begun to revise the history of the Mozambican War of Independence to distort it to suit FRELIMO's new, contradictory pro-capitalist beliefs.[27]

In 1990 a revised constitution was adopted which introduced a multi-party system to Mozambique and ended one-party rule. The revisions also removed all references to socialism from the constitution and resulted in the People's Republic of Mozambique being renamed to the Republic of Mozambique.[28]

The civil war conflict continued under a lessened pace until 1992 when the Rome General Peace Accords was signed. With the end of the civil war elections were scheduled for 1994 under the new pluralistic system. FRELIMO and RENAMO campaigned heavily for the elections. FRELIMO ultimately won the elections with 53.3% of the vote with an 88% voter turnout.[29] RENAMO contested the election results and threatened to return to violence, however under both internal and external pressure RENAMO eventually accepted the results.

Throughout the mid to late 1990s, FRELIMO moved towards social democratic views, as further liberalisation continued the government received further support and aid from countries such as the United Kingdom and United States. Mozambique became a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, despite not being a former British colony, for its role in ensuring the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980.

At the elections in late 1999, President Chissano was re-elected with 52.3% of the vote, and FRELIMO secured 133 of 250 parliamentary seats. Owing to accusations of election fraud and several cases of corruption, Chissano's government was widely criticised. But, under Chissano's leadership, Mozambique has continued to be regarded as a model of fast and sustainable economic growth and democratic changes.

2000s onwards

In early 2001 Chissano announced his intention to not stand for the 2004 presidential election, although the constitution permitted him to do so.

In 2002, during its 8th Congress, the party selected Armando Guebuza as its candidate for the presidential election held on December 1–2, 2004. As expected given FRELIMO's majority status, he won, gaining about 60% of the vote. At the legislative elections of the same date, the party won 62.0% of the popular vote and 160 of 250 seats in the national assembly.

RENAMO and some other opposition parties made claims of election fraud and denounced the result. International observers (among others, members of the European Union Election Observation Mission to Mozambique and the Carter Center) supported these claims, criticizing the National Electoral Commission (CNE) for failing to conduct fair and transparent elections. They listed numerous cases of improper conduct by the electoral authorities that benefited FRELIMO. However, the EU observers concluded that the elections shortcomings probably did not affect the presidential election's final result.

Foreign support

FRELIMO has received support from the governments of Tanzania, Algeria, Ghana, Zambia, Libya, Sweden,[30] Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, Egypt, SFR Yugoslavia[31] and Somalia.[32]

Mozambican presidents representing the Frelimo Party

- Samora Machel: 25 June 1975 – 19 October 1986

- Joaquim Chissano: 6 November 1986 – 2 February 2005

- Armando Guebuza: 2 February 2005 – 15 January 2015

- Filipe Nyusi: 15 January 2015 – present

Other prominent members

- José Ibraimo Abudo, Justice minister since 1994

- Isabel Casimiro, Frelimo MP, sociologist and professor

- Basilio Muhate, Chairman of Frelimo Youth Organization since 2010

- Sharfudine Khan, Ambassador of Mozambique (After Liberation)

Electoral history

Presidential elections

| Election | Party candidate | Votes | % | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Joaquim Chissano | 2,633,740 | 53.30% | Elected |

| 1999 | 2,338,333 | 52.29% | Elected | |

| 2004 | Armando Guebuza | 2,004,226 | 63.74% | Elected |

| 2009 | 2,974,627 | 75.01% | Elected | |

| 2014 | Filipe Nyusi | 2,778,497 | 57.03% | Elected |

| 2019 | 4,639,172 | 73.46% | Elected |

Assembly elections

| Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | 210 / 210 |

||||

| 1986 | 249 / 259 |

||||

| 1994 | 2,115,793 | 44.3% | 129 / 250 |

||

| 1999 | 2,005,713 | 48.5% | 133 / 250 |

||

| 2004 | 1,889,054 | 62.0% | 160 / 250 |

||

| 2009 | 2,907,335 | 74.7% | 191 / 250 |

||

| 2014 | 2,575,995 | 55.9% | 144 / 250 |

||

| 2019 | 4,323,298 | 71.3% | 184 / 250 |

See also

Notes

- "Dar-es-Salaam once a home for revolutionaries". sundayworld.co.za. 29 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- http://www.frelimo.org.mz/frelimo/Baixar/ESTATUTOS-11- CONGRESSO.pdf

- Simões Reis, Guilherme (8 July 2012). "The Political-Ideological Path of FRELIMO in Mozambique, from 1962 to 2012" (PDF). ipsa.org. p. 9.

- "Election of FRELIMO Candidate Goes Into the Night". Mozambique News Agency. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- Martin Rupiya, "Historical context: War and Peace in Mozambique", Conciliation Resources, php

- Samora Machel, "Unidade, Trabalho, Vigilância" 1974

- Unknown Author, "Mozambique Radio Seized by Ex‐Portuguese Soldiers" The New York Times, 7 September 1974

- J. Cabrita, Mozambique: A Tortuous Road to Democracy, New York: Macmillan, 2001. ISBN 978-0-333-92001-5

- Mario Mouzinho Literacy in Mozambique: education for all challenges UNESCO, 2006

- Various, Comissão de Implementação dos Conselhos de Produção 1977

- Directivas Económicas e Sociais Documentos do III Congresso da FRELIMO, 1977

- Samora Machel, O Partido e as Classes Trabalhadoras Moçambicanas na Edificação da Democracia Popular Documentos do III Congresso da FRELIMO, 1977

- R. Madeley, D. Jelley and P. O'Keefe, The Advent of Primary Health Care in Mozambique,1983

- Ferrinho P. and Omar C, The Human Resources for Health Situation in Mozambique, 2006

- Directivas Económicas e Sociais da 4 Congresso FRELIMO, Colecção 4 Congresso FRELIMO, 1983

- Joseph Hanlon, "Beggar Your Neighbours: Apartheid Power in Southern Africa, 1986

- Henry Kamm, Deadly Famine in Mozambique called Inevitable, The New York Times, Nov 18. 1984

- Otto Roesch, Rural Mozambique since the Frelimo Party Fourth Congress, Review of African Political Economy, 1988

- Merle L. Bowen, Peasant Agriculture in Mozambique, Canadian Journal of African Studies, 1989

- Bob and Amy Coen, "Mozambique: The Struggle for Survival" Video Africa, 1987

- Paul Fauvet, "Carlos Cardoso: Telling the Truth in Mozambique" Double Storey Books, 2003

- Christie, Iain, Machel of Mozambique, Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1988.

- Moderate Marxist Succeeds Machel in Mozambique, Associated Press, Nov 03 1986

- Dez meses depois do PRE, é encorajador crescimento atingido, considera Ministro Osman, Notícias, 14 Oct 1987

- Directivas Económicas e Sociais da 5 Congresso FRELIMO, Colecção 5 Congresso FRELIMO, 1989

- Barry Munslow, Marxism‐Leninism in reverse, the Fifth Congress of FRELIMO, Journal of Communist Studies, 1990

- Alice Dinerman, "Independence redux in postsocialist Mozambique"], IPRI Revista Relações Internacionais n.º 15, Setembro 2007

- "Constitution of the Republic of Mozambique"], Assembleia Popular, 1990

- Elections in Mozambique African elections database

- Rui Mateus, In Contos Proibidos (p. 41)

- University of Michigan. Southern Africa: The Escalation of a Conflict, 1976, p. 99

- FRELIMO. Departamento de Informação e Propaganda, Mozambique revolution, Page 10

Further reading

- Basto, Maria-Benedita, "Writing a Nation or Writing a Culture? Frelimo and Nationalism During the Mozambican Liberation War" in Eric Morier-Genoud (ed.) Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

- Bowen, Merle. The State Against the Peasantry: Rural Struggles in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press Of Virginia, 2000.

- Derluguian, Georgi, "The Social Origins of Good and Bad Governance: Re-interpreting the 1968 Schism in Frelimo" in Eric Morier-Genoud (ed.) Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

- Morier-Genoud, Eric, “Mozambique since 1989: Shaping democracy after Socialism” in A.R.Mustapha & L.Whitfield (eds), Turning Points in African Democracy (Oxford: James Currey, 2009), pp. 153–166

- Opello, Walter C. "Pluralism and elite conflict in an independence movement: FRELIMO in the 1960s", Journal of Southern African Studies, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1975

- Simpson, Mark, "Foreign and Domestic Factors in the Transformation of Frelimo", Journal of Modern African Studies, Volume 31, no.02, June 1993, pp 309–337

- Sumich, Jason, "The Party and the State: Frelimo and Social Stratification in Post-socialist Mozambique", Development and Change, Volume 41, no. 4, July 2010, pp. 679–698

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to FRELIMO. |