Flavr Savr

Flavr Savr (also known as CGN-89564-2; pronounced "flavor saver"), a genetically modified tomato, was the first commercially grown genetically engineered food to be granted a license for human consumption. It was produced by the Californian company Calgene, and submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1992.[1] On May 18, 1994,[2] the FDA completed its evaluation of the Flavr Savr tomato and the use of APH(3')II, concluding that the tomato "is as safe as tomatoes bred by conventional means" and "that the use of aminoglycoside 3'-phosphotransferase II is safe for use as a processing aid in the development of new varieties of tomato, rapeseed oil, and cotton intended for food use." It was first sold in 1994, and was only available for a few years before production ceased in 1997.[3] Calgene made history, but mounting costs prevented the company from becoming profitable, and it was eventually acquired by Monsanto Company.

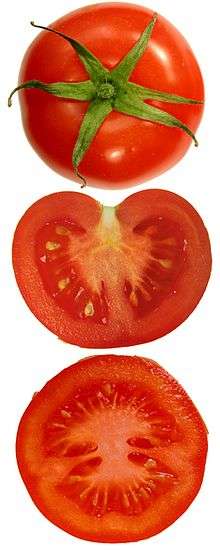

Characteristics

Tomatoes have a short shelf-life in which they remain firm and ripe. This lifetime may be shorter than the time needed for them to reach market when shipped from winter growing areas to markets in the north, and the softening process can also lead to more of the fruit being damaged during transit.

To address this, tomatoes intended for shipping are often picked while they are unripe, or "green", and then prompted to ripen just before delivery through the use of ethylene gas which acts as a plant hormone. The downside to this approach is that the tomato does not complete its natural growing process, and the final flavor suffers as a result.[4]

Through genetic engineering, Calgene hoped to slow down the ripening process of the tomato and thus prevent it from softening, while still allowing the tomato to retain its natural colour and flavour. This would allow it to fully ripen on the vine and still be shipped long distances without it going soft.[3]

The Flavr Savr was made more resistant to rotting by adding an antisense gene which interferes with the production of the enzyme polygalacturonase. The enzyme normally degrades pectin in the cell walls and results in the softening of fruit which makes them more susceptible to being damaged by fungal infections.

Flavr Savr turned out to disappoint researchers in that respect, as the antisensed PG gene had a positive effect on shelf life, but not on the fruit's firmness, so the tomatoes still had to be harvested like any other unmodified vine-ripe tomatoes.[5] An improved flavor, later achieved through traditional breeding of Flavr Savr and better tasting varieties, would also contribute to selling Flavr Savr at a premium price at the supermarket.

The FDA stated that special labeling for these modified tomatoes was not necessary because they have the essential characteristics of non-modified tomatoes. Specifically, there was no evidence for health risks, and the nutritional content was unchanged.[3]

The failure of the Flavr Savr has been attributed to Calgene's inexperience in the business of growing and shipping tomatoes.[6]

Tomato paste

In the UK, Zeneca produced a tomato paste that used technology similar to the Flavr Savr.[7] Don Grierson was involved in the research to make the genetically modified tomato.[8] Due to the characteristics of the tomato, it was cheaper to produce than conventional tomato paste, resulting in the product being 20% cheaper. Between 1996 and 1999, 1.8 million cans, clearly labelled as genetically engineered, were sold in the major supermarket chains Sainsbury's and Safeway UK. At one point the paste outsold normal tomato paste but sales fell in the autumn of 1998.

The House of Commons of the United Kingdom published a report in which they stated that the decline in sales during this period was linked to changing consumer perceptions of genetically modified crops.[9] The report identified several possible factors, including product labeling and perception of choice, lobbying campaigns, and media attention. It concluded that the tone of media reports on the subject underwent a "fundamental shift" in response to a high-profile incident in which Dr. Arpad Pusztai, a researcher for Rowett Research Institute, was fired after making a televised claim about detrimental health effects in lab rats fed a diet of genetically modified potatoes (see the Pusztai affair). Subsequent peer review and testimony by Dr. Pusztai led the House Science and Technology Select Committee to conclude that his initial claim was "contradicted by his own evidence." In the intervening period, Sainsbury's and Safeway both pledged that none of their house brand products would contain genetically modified ingredients.[10]

References

- Redenbaugh, Keith, Bill Hiatt, Belinda Martineau, Matthew Kramer, Ray Sheehy, Rick Sanders, Cathy Houck and Don Emlay (1992). Safety Assessment of Genetically Engineered Fruits and Vegetables: A Case Study of the Flavr Savr Tomato. CRC Press. p. 288.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Stone, Brad. "The Flavr Savr Arrives". Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- Weasel, Lisa H. 2009. Food Fray. Amacom Publishing

- "The Original Genetically-modified Tomato You'll Never Eat".

- Martineau, Belinda. 2001. First Fruit: The Creation of the Flavr Savr Tomato and the Birth of Biotech Food. McGraw-Hill.

- Charles, Dan. 2001. Lords of The Harvest. Perseus Publishing. 144-148.

- Center for Environmental Risk Assessment. "GM Crop Database:Tomato". International Life Sciences Institute.

- "A puree genius at his work". Times Higher Education. 1998-07-17. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- House of Commons Science; Technology Committee (May 18, 1999). "Scientific Advisory System: Genetically Modified Foods". Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato G. Bruening & J.M. Lyons, California Agriculture 54(4):6-7

External links

- "The transgenic tomato" "Purpose: To show a general reading audience (perhaps readers of a popular science magazine) that genetically engineered crops are needed and safe to consume by discussing the development of a successful genetically engineered crop, the FLAVR SAVR tomato."

- Daniel Puzo (1992-06-04). "The Biotech Debate". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2015-11-08.