Fisher transformation

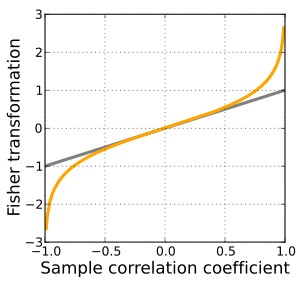

In statistics, the Fisher transformation (aka Fisher z-transformation) can be used to test hypotheses about the value of the population correlation coefficient ρ between variables X and Y.[1][2] This is because, when the transformation is applied to the sample correlation coefficient, the sampling distribution of the resulting variable is approximately normal, with a variance that is stable over different values of the underlying true correlation.

Definition

Given a set of N bivariate sample pairs (Xi, Yi), i = 1, ..., N, the sample correlation coefficient r is given by

Here stands for the covariance between the variables and and stands for the standard deviation of the respective variable. Fisher's z-transformation of r is defined as

where "ln" is the natural logarithm function and "arctanh" is the inverse hyperbolic tangent function.

If (X, Y) has a bivariate normal distribution with correlation ρ and the pairs (Xi, Yi) are independent and identically distributed, then z is approximately normally distributed with mean

and standard error

where N is the sample size, and ρ is the true correlation coefficient.

This transformation, and its inverse

can be used to construct a large-sample confidence interval for r using standard normal theory and derivations. See also application to partial correlation.

Derivation

To derive the Fisher transformation, one starts by considering an arbitrary increasing function of , say . Finding the first term in the large- expansion of the corresponding skewness results in

Making it equal to zero and solving the corresponding differential equation for yields the function. Similarly expanding the mean and variance of , one gets

and

respectively. The extra terms are not part of the usual Fisher transformation. For large values of and small values of they represent a large improvement of accuracy at minimal cost, although they greatly complicate the computation of the inverse as a closed-form expression is not available. The near-constant variance of the transformation is the result of removing its skewness – the actual improvement is achieved by the latter, not by the extra terms. Including the extra terms yields:

which has, to an excellent approximation, a standard normal distribution.[3]

Discussion

The Fisher transformation is an approximate variance-stabilizing transformation for r when X and Y follow a bivariate normal distribution. This means that the variance of z is approximately constant for all values of the population correlation coefficient ρ. Without the Fisher transformation, the variance of r grows smaller as |ρ| gets closer to 1. Since the Fisher transformation is approximately the identity function when |r| < 1/2, it is sometimes useful to remember that the variance of r is well approximated by 1/N as long as |ρ| is not too large and N is not too small. This is related to the fact that the asymptotic variance of r is 1 for bivariate normal data.

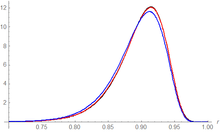

The behavior of this transform has been extensively studied since Fisher introduced it in 1915. Fisher himself found the exact distribution of z for data from a bivariate normal distribution in 1921; Gayen in 1951[4] determined the exact distribution of z for data from a bivariate Type A Edgeworth distribution. Hotelling in 1953 calculated the Taylor series expressions for the moments of z and several related statistics[5] and Hawkins in 1989 discovered the asymptotic distribution of z for data from a distribution with bounded fourth moments.[6]

Other uses

While the Fisher transformation is mainly associated with the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for bivariate normal observations, it can also be applied to Spearman's rank correlation coefficient in more general cases.[7] A similar result for the asymptotic distribution applies, but with a minor adjustment factor: see the latter article for details.

See also

- Data transformation (statistics)

- Meta-analysis (this transformation is used in meta analysis for stabilizing the variance)

- Partial correlation

- R implementation

References

- Fisher, R. A. (1915). "Frequency distribution of the values of the correlation coefficient in samples of an indefinitely large population". Biometrika. 10 (4): 507–521. doi:10.2307/2331838. hdl:2440/15166. JSTOR 2331838.

- Fisher, R. A. (1921). "On the 'probable error' of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample" (PDF). Metron. 1: 3–32.

- Vrbik, Jan (December 2005). "Population moments of sampling distributions". Computational Statistics. 20 (4): 611–621. doi:10.1007/BF02741318.

- Gayen, A. K. (1951). "The Frequency Distribution of the Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient in Random Samples of Any Size Drawn from Non-Normal Universes". Biometrika. 38 (1/2): 219–247. doi:10.1093/biomet/38.1-2.219. JSTOR 2332329.

- Hotelling, H (1953). "New light on the correlation coefficient and its transforms". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 15 (2): 193–225. JSTOR 2983768.

- Hawkins, D. L. (1989). "Using U statistics to derive the asymptotic distribution of Fisher's Z statistic". The American Statistician. 43 (4): 235–237. doi:10.2307/2685369. JSTOR 2685369.

- Zar, Jerrold H. (2005). Spearman Rank Correlation: Overview. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. doi:10.1002/9781118445112.stat05964. ISBN 9781118445112.