Al-Ashdaq

Abū Umayya ʿAmr ibn Saʿīd ibn al-ʿĀṣ al-Umawī (Arabic: عمر بن سعيد بن العاص بن أمية الأموي; died 689/90), better known as al-Ashdaq (الأشدق), was an Umayyad prince, general and a contender for the caliphal throne. He served as the governor of Medina in 680, during the reign of Caliph Yazid I (r. 680–683) and later fought off attempts by the Zubayrids to conquer Syria in 684 and 685 during the reign of Caliph Marwan I. His attempted coup against Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) in 689 ended with his surrender and ultimately his execution by Abd al-Malik himself.

Life

Amr was the son of the Umayyad statesman Sa'id ibn al-As and Umm al-Banin bint al-Hakam, the sister of another Umayyad statesman, Marwan ibn al-Hakam.[1] He was nicknamed "al-Ashdaq" (the Widemouthed).[2] When Sa'id died in 679, al-Ashdaq became the leader of this branch of the Umayyad clan.[3] At the end of the reign of Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), he was governor of Mecca but was then appointed the governor of Medina at the accession of Caliph Yazid I (r. 680–683).[4] When the Umayyads were driven out of Mecca during the revolt of Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr in 682, al-Ashdaq was ordered by Yazid to send an army against the Zubayrids in the city.[4] Al-Ashdaq appointed Ibn al-Zubayr's brother, Amr, to lead the expedition, but the force was defeated and Amr was executed by Ibn al-Zubayr.[4] Toward the end of 683, al-Ashdaq was dismissed,[4] Yazid died and was succeeded by his son, Mu'awiya II. The latter was ill and died a few months later, causing a leadership crisis in the Umayyad Caliphate, which saw most of its provinces recognize Ibn al-Zubayr as caliph.

When the pro-Umayyad Arab tribal nobility of Syria, chief among them the chieftain of Banu Kalb, elected Marwan ibn al-Hakam as caliph at the Jabiya summit of 684, it was stipulated that Yazid's then-young son Khalid would succeed Marwan, followed by al-Ashdaq.[4] The latter commanded the right wing of Marwan's army during the Battle of Marj Rahit later that year, in which the Umayyads scored a resounding victory over the pro-Zubayrid Qaysi tribes of Syria.[5] During Marwan's expedition to wrest control of Egypt from its Zubayrid governor in 685, al-Ashdaq was present and delivered an address proclaiming Marwan's sovereignty from the pulpit of the mosque in Fustat.[6] Afterward, al-Ashdaq was dispatched by Marwan to stave off an invasion of Palestine by Mus'ab ibn al-Zubayr, who was attempting to conquer Umayyad Syria during Marwan's absence.[4][6] He then joined Marwan and took up residence in the Umayyad capital of Damascus.[6] The caliph remained wary of al-Ashdaq's ambitions to the caliphate, particularly due to his popularity among the Syrian Arab nobility and his close kinship to Marwan, who was his maternal uncle and paternal relative as well.[4] Marwan resolved to avoid the potential leadership bids of al-Ashdaq and Khalid by having his sons Abd al-Malik and Abd al-Aziz, in that order, recognized by the Syrian nobility as his chosen successors.[4]

Abd al-Malik succeeded his father in late 685 but remained suspicious of al-Ashdaq. The latter did not relinquish his claims and viewed Abd al-Malik's accession as a violation of the arrangements reached in Jabiya.[4] When the caliph left Damascus on a military campaign against Zubayrid-held Iraq in 689, al-Ashdaq took advantage of his absence to launch a revolt, seize the city and declare his right as sovereign.[4] This compelled Abd al-Malik to abandon his campaign and address al-Ashdaq's rebellion.[4] In the ensuing standoff in Damascus between their supporters, Abd al-Malik offered al-Ashdaq amnesty in return for his surrender, to which al-Ashdaq obliged.[4] However, Abd al-Malik remained distrustful of al-Ashdaq and had him summoned to his palace in Damascus, where he executed him in 689/90.[4]

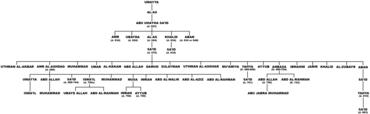

Family

Al-Ashdaq's sons Umayya, Sa'id, Isma'il and Muhammad, all born to al-Ashdaq's wife Umm Habib bint Hurayth,[7] were later reconciled with Abd al-Malik following the latter's victory over the Zubayrids in 692.[8] Sa'id, who had participated in his father's revolt, subsequently migrated to Medina, then to Kufa.[9] He became a mentor of Khalid al-Qasri, who served as governor of Iraq in 724–738.[9] Khalid's father Abdallah had been the head of al-Ashdaq's shurṭa (security forces).[9] Sa'id was later reported to have visited the court of the Umayyad caliph Yazid II in 744.[9] Isma'il, who also participated in his father's rebellion, lived in ascetic seclusion near Medina into the beginning of the Abbasid period (post-750) and the Umayyad caliph Umar II (r. 717–720) reportedly considered appointing him his successor for his reputed piety. [10][11] He was spared execution by the Abbasid governor of Medina Dawud ibn Ali.[10] Al-Ashdaq's daughter Umm Kulthum was also born to Umm Habib.[7]

From his wife Sawda bint al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, the sister of Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, al-Ashdaq had his sons Abd al-Malik and Abd al-Aziz and daughter Ramla.[7] He was also married to A'isha bint Muti, the sister of Abd Allah ibn Muti from the Banu Adi clan of Quraysh, who bore his sons Musa and Imran. From his Kalbite wife Na'ila bint al-Furays he had a daughter, Umm Musa.[7] He also had children from two ummahat awlad (concubines), one of whom bore his sons Abd Allah and Abd al-Rahman and the other his daughter Umm Imran.[7]

References

- Bewley 2000, p. 289.

- Hillenbrand 1989, p. 195, note 987.

- Bosworth 1995, p. 853.

- Zetterstéen 1960, p. 453.

- Hawting 1989, p. 59.

- Hawting 1989, p. 64.

- Bewley 2000, p. 154.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 166.

- Blankinship 1989, p. 174, note 599.

- Bewley 2000, pp. 289–290.

- Landau-Tasseron 1998, p. 334, note 1564.

Bibliography

- Bewley, Aisha (2000). The Men of Madina, Volume 2. Ta-Ha Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXV: The End of Expansion: The Caliphate of Hishām, A.D. 724–738/A.H. 105–120. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-569-9.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1995). "Saʿīd b. al-ʿĀṣ". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 853. ISBN 90-04-09834-8.

- Fishbein, Michael, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXI: The Victory of the Marwānids, A.D. 685–693/A.H. 66–73. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0221-4.

- Hawting, G.R., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XX: The Collapse of Sufyānid Authority and the Coming of the Marwānids: The Caliphates of Muʿāwiyah II and Marwān I and the Beginning of the Caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik, A.D. 683–685/A.H. 64–66. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-855-3.

- Hillenbrand, Carole, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXVI: The Waning of the Umayyad Caliphate: Prelude to Revolution, A.D. 738–744/A.H. 121–126. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-810-2.

- Landau-Tasseron, Ella, ed. (1998). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIX: Biographies of the Prophet's Companions and their Successors: al-Ṭabarī's Supplement to his History. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2819-1.

- Zetterstéen, K. V. (1960). "ʿAmr b. Saʿīd". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 453–454. OCLC 495469456.