Ferdowsi

Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi (Persian: ابوالقاسم فردوسی توسی; c. 940–1020), or just Ferdowsi (فردوسی)[1] was a Persian poet[2][3] and the author of Shahnameh ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poems created by a single poet, and the national epic of Greater Iran. Ferdowsi is celebrated as the most influential figure in Persian literature and one of the greatest in the history of literature.[4]

.jpg) Statue of Ferdowsi in Tus | |

| Native name | |

| Born | c. 940 Tus, Samanid Empire |

| Died | 1020 (aged 79–80) Tus, Ghaznavid Empire |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | Early Modern Persian |

| Period | Samanids and Ghaznavids |

| Genre | Persian poetry, national epic |

.jpg)

Name

Except for his kunya (ابوالقاسم – Abu'l-Qāsim) and his laqab (فِردَوسی – Ferdowsī, meaning 'paradisic'), nothing is known with any certainty about his full name. From an early period on, he has been referred to by different additional names and titles, the most common one being حکیم / Ḥakīm ("philosopher").[5] Based on this, his full name is given in Persian sources as حکیم ابوالقاسم فردوسی توسی / Ḥakīm Abu'l-Qāsim Firdowsī Țusī. Due to the non-standardized transliteration from Persian into English, different spellings of his name are used in English works, including Firdawsi, Firdusi, Firdosi, Firdausi, etc. The Encyclopaedia of Islam uses the spelling Firdawsī, based on the standardized transliteration method of the German Oriental Society.[1] The Encyclopædia Iranica, which uses a modified version of the same method (with a stronger emphasis on Persian intonations), gives the spelling Ferdowsī.[5] In both cases, the -ow and -aw are to be pronounced as a diphthong ([aʊ̯]), reflecting the original Arabic and the early New Persian pronunciation of the name. The modern Tajik transliteration of his name in Cyrillic script is Ҳаким Абулқосим Фирдавсӣ Тӯсӣ.

Life

Family

Ferdowsi was born into a family of Iranian landowners (dehqans) in 940 in the village of Paj, near the city of Tus, in the Khorasan region of the Samanid Empire, which is located in the present-day Razavi Khorasan Province of northeastern Iran.[6] Little is known about Ferdowsi's early life. The poet had a wife, who was probably literate and came from the same dehqan class. He had a son, who died at the age of 37, and was mourned by the poet in an elegy which he inserted into the Shahnameh.[5]

Background

Ferdowsi belonged to the class of dehqans. These were landowning Iranian aristocrats who had flourished under the Sassanid dynasty (the last pre-Islamic dynasty to rule Iran) and whose power, though diminished, had survived into the Islamic era which followed the Islamic conquests of the 7th century. The dehqans were attached to the pre-Islamic literary heritage, as their status was associated with it (so much so that dehqan is sometimes used as a synonym for "Iranian" in the Shahnameh). Thus they saw it as their task to preserve the pre-Islamic cultural traditions, including tales of legendary kings.[5][6]

The Islamic conquests of the 7th century brought gradual linguistic and cultural changes to the Iranian Plateau. By the late 9th century, as the power of the caliphate had weakened, several local dynasties emerged in Greater Iran.[6] Ferdowsi grew up in Tus, a city under the control of one of these dynasties, the Samanids, who claimed descent from the Sassanid general Bahram Chobin (whose story Ferdowsi recounts in one of the later sections of the Shahnameh).[7] The Samanid bureaucracy used the New Persian language, which had been used to bring Islam to the Eastern regions of the Iranian world and supplanted local languages, and commissioned translations of Pahlavi texts into New Persian. Abu Mansur Muhammad, a dehqan and governor of Tus, had ordered his minister Abu Mansur Mamari to invite several local scholars to compile a prose Shahnameh ("Book of Kings"), which was completed in 1010.[8] Although it no longer survives, Ferdowsi used it as one of the sources of his epic. Samanid rulers were patrons of such important Persian poets as Rudaki and Daqiqi, and Ferdowsi followed in the footsteps of these writers.[9]

Details about Ferdowsi's education are lacking. Judging by the Shahnameh, there is no evidence he knew either Arabic or Pahlavi.[5]

Life as a poet

It is possible that Ferdowsi wrote some early poems which have not survived. He began work on the Shahnameh around 977, intending it as a continuation of the work of his fellow poet Daqiqi, who had been assassinated by his slave. Like Daqiqi, Ferdowsi employed the prose Shahnameh of ʿAbd-al-Razzāq as a source. He received generous patronage from the Samanid prince Mansur and completed the first version of the Shahnameh in 994.[5] When the Turkic Ghaznavids overthrew the Samanids in the late 990s, Ferdowsi continued to work on the poem, rewriting sections to praise the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud. Mahmud's attitude to Ferdowsi and how well he rewarded the poet are matters which have long been subject to dispute and have formed the basis of legends about the poet and his patron (see below). The Turkic Mahmud may have been less interested in tales from Iranian history than the Samanids.[6] The later sections of the Shahnameh have passages which reveal Ferdowsi's fluctuating moods: in some he complains about old age, poverty, illness and the death of his son; in others, he appears happier. Ferdowsi finally completed his epic on 8 March 1010. Virtually nothing is known with any certainty about the last decade of his life.[5]

Tomb

Ferdowsi was buried in his own garden, burial in the cemetery of Tus having been forbidden by a local cleric. A Ghaznavid governor of Khorasan constructed a mausoleum over the grave and it became a revered site. The tomb, which had fallen into decay, was rebuilt between 1928 and 1934 by the Society for the National Heritage of Iran on the orders of Rezā Shāh, and has now become the equivalent of a national shrine.[10]

Legend

According to legend, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni offered Ferdowsi a gold piece for every couplet of the Shahnameh he wrote. The poet agreed to receive the money as a lump sum when he had completed the epic. He planned to use it to rebuild the dykes in his native Tus. After thirty years of work, Ferdowsi finished his masterpiece. The sultan prepared to give him 60,000 gold pieces, one for every couplet, as agreed. However, the courtier whom Mahmud had entrusted with the money despised Ferdowsi, regarding him as a heretic, and he replaced the gold coins with silver. Ferdowsi was in the bath house when he received the reward. Finding it was silver and not gold, he gave the money away to the bathkeeper, a refreshment seller, and the slave who had carried the coins. When the courtier told the sultan about Ferdowsi's behaviour, he was furious and threatened to execute him. Ferdowsi fled Khorasan, having first written a satire on Mahmud, and spent most of the remainder of his life in exile. Mahmud eventually learned the truth about the courtier's deception and had him either banished or executed. By this time, the aged Ferdowsi had returned to Tus. The sultan sent him a new gift of 60,000 gold pieces, but just as the caravan bearing the money entered the gates of Tus, a funeral procession exited the gates on the opposite side: the poet had died from a heart attack.[11]

Works

Ferdowsi's Shahnameh is the most popular and influential national epic in Iran and other Persian-speaking nations. The Shahnameh is the only surviving work by Ferdowsi regarded as indisputably genuine. He may have written poems earlier in his life but they no longer exist. A narrative poem, Yūsof o Zolaykā (Joseph and Zuleika), was once attributed to him, but scholarly consensus now rejects the idea it is his.[5] There has also been speculation about the satire Ferdowsi allegedly wrote about Mahmud of Ghazni after the sultan failed to reward him sufficiently. Nezami Aruzi, Ferdowsi's early biographer, claimed that all but six lines had been destroyed by a well-wisher who had paid Ferdowsi a thousand dirhams for the poem. Introductions to some manuscripts of the Shahnameh include verses purporting to be the satire. Some scholars have viewed them as fabricated; others are more inclined to believe in their authenticity.[12]

Gallery

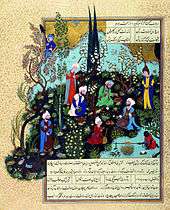

_of_Firdawsi%2C_late_15th-early_16th_century.jpg) The Sasanian King Khusraw and Courtiers in a Garden, page from a manuscript of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), late 15th–early 16th century, Brooklyn Museum

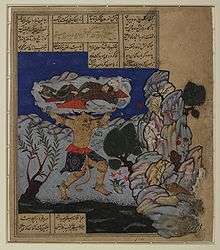

The Sasanian King Khusraw and Courtiers in a Garden, page from a manuscript of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), late 15th–early 16th century, Brooklyn Museum Scene from the Shahnameh: the Akvan Div throws the sleeping Rostam into the sea

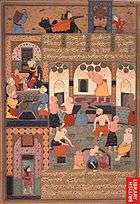

Scene from the Shahnameh: the Akvan Div throws the sleeping Rostam into the sea Bath scene

Bath scene

The Simurgh, a mythical bird from the Shahnameh, relief from Ferdowsi's mausoleum

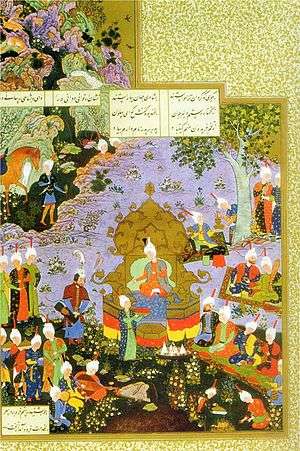

The Simurgh, a mythical bird from the Shahnameh, relief from Ferdowsi's mausoleum A scene from the Shahnameh depicting the Parthian king Artaban facing the Sassanid king Ardashir I

A scene from the Shahnameh depicting the Parthian king Artaban facing the Sassanid king Ardashir I

Influence

Ferdowsi is one of the undisputed giants of Persian literature. After Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, a number of other works similar in nature surfaced over the centuries within the cultural sphere of the Persian language. Without exception, all such works were based in style and method on Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, but none of them could quite achieve the same degree of fame and popularity as Ferdowsi's masterpiece.

Ferdowsi has a unique place in Persian history because of the strides he made in reviving and regenerating the Persian language and cultural traditions. His works are cited as a crucial component in the persistence of the Persian language, as those works allowed much of the tongue to remain codified and intact. In this respect, Ferdowsi surpasses Nizami, Khayyám, Asadi Tusi and other seminal Persian literary figures in his impact on Persian culture and language. Many modern Iranians see him as the father of the modern Persian language.

Ferdowsi in fact was a motivation behind many future Persian figures. One such notable figure was Rezā Shāh Pahlavi, who established an Academy of Persian Language and Literature, in order to attempt to remove Arabic and French words from the Persian language, replacing them with suitable Persian alternatives. In 1934, Rezā Shāh set up a ceremony in Mashhad, Khorasan, celebrating a thousand years of Persian literature since the time of Ferdowsi, titled "Ferdowsi Millennial Celebration", inviting notable European as well as Iranian scholars.[13] Ferdowsi University of Mashhad is a university established in 1949 that also takes its name from Ferdowsi.

Ferdowsi's influence in the Persian culture is explained by the Encyclopædia Britannica:[14]

- The Persians regard Ferdowsi as the greatest of their poets. For nearly a thousand years they have continued to read and to listen to recitations from his masterwork, the Shah-nameh, in which the Persian national epic found its final and enduring form. Though written about 1,000 years ago, this work is as intelligible to the average, modern Iranian as the King James Version of the Bible is to a modern English-speaker. The language, based as the poem is on a Dari original, is pure Persian with only the slightest admixture of Arabic.

The library at Wadham College, Oxford University was named the Ferdowsi Library, and contains a specialised Persian section for scholars.

See also

- Iranian Studies

- Ferdowsi millennial celebration

- Ferdowsi University of Mashhad

- List of Persian poets and authors

- Rumi (1207–1273), arguably the internationally most famous Persian poet

- Persian literature

- Sassanid Empire

- List of mausoleums

- Jerry Clinton (1937–2003), US Ferdowsi scholar

- Ferdowsi (1934 film)

Notes

- Huart/Massé/Ménage: Firdawsī. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, Leiden. CD-Version (2011)

- "Search Results – Brill Reference". referenceworks.brillonline.com. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Abū l-Qāsim Firdawsī (329–411/940–1020) was a Persian poet, one of the greatest writers of epic and author of the Shāhnāma (“Book of kings”).

- Kia, Mehrdad (27 June 2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 9781610693912.

- Hamid Dabashi (2012). The World of Persian Literary Humanism. Harvard University Press.

- Shahbazi, A. Shahpur (26 January 2012). "Ferdowsi". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Davis 2006, p. xviii

- Frye 1975, p. 200

- "Abu Mansur". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Frye 1975, p. 202

- Shahbazi, A. Shahpur (26 January 2012). "Mausoleum". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Donna Rosenberg (1997). Folklore, myths, and legends: a world perspective. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 99–101.

- Shahbazi, A. Shahpur (26 January 2012). "Hajw-nāma". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Cyrus Ghani, Sirus Ghani (2001). Iran and the rise of Reza Shah: from Qajar collapse to Pahlavi rule. I.B.Tauris. p. 400.

- "Ferdowsi". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

References

- Davis, Dick (2006). Introduction. Shahnameh: the Persian book of kings. By Ferdowsi, Abolqasem. Viking. ISBN 0-670-03485-1.

- Frye, Richard N. (1975). The Golden Age of Persia. Weidenfeld.

- Browne, E.G. (1998). Literary History of Persia. ISBN 0-7007-0406-X.

- Rypka, Jan (1968). History of Iranian Literature. Reidel. ISBN 90-277-0143-1. OCLC 460598.

- Aghaee, Shirzad (1997). Imazh-ha-ye mehr va mah dar Shahnameh-ye Ferdousi (Sun and Moon in the Shahnameh of Ferdousi. Spånga, Sweden. ISBN 91-630-5369-1.

- Aghaee, Shirzad (1993). Nam-e kasan va ja'i-ha dar Shahnameh-ye Ferdousi (Personalities and Places in the Shahnameh of Ferdousi. Nyköping, Sweden. ISBN 91-630-1959-0.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef. Ancient Persia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-675-1.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1991). Ferdowsi: a critical biography. Harvard University, Center for Middle Eastern Studies. ISBN 0-939214-83-0.

- Mackey, Sandra; Harrop, W. Scott (2008). The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the soul of a nation. University of Michigan. ISBN 0-525-94005-7.

- Chopra, R. M. (2014). Great Poets of Classical Persian. Kolkata: Sparrow. ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5.

- Waghmar, Burzine and Sharma, Sunil (2016). Firdawsi: a Scholium. In Sunil Sharma and Burzine Waghmar, eds. Firdawsii Millennium Indicum: Proceedings of the Shahnama Millenary Seminar, K R Cama Oriental Institute, Mumbai, 8–9 January 2011, pp 7–18. Mumbai: K. R. Cama Oriental Institute, ISBN 978-93-81324-10-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ferdowsi. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Ferdowsi |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ferdowsi |

- Works by Firdawsi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ferdowsi at Internet Archive

- Khosrow Nāghed, In the Workshop of Thought and Imagination of the Master of Tūs (Dar Kargāh-e Andisheh va Khiāl-e Ostād-e Tūs), in Persian, Radio Zamāneh, 5 August 2008.

- Ferdowsi: Poems Ferdowsi's poems in English

- Iraj Bashiri, The Shahname of Firdowsi

- Ferdowsi Museum photos

- Ferdowsi Tomb photos

- A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- Ferdowsi Quotes

.png)