Daqiqi

Abu Mansur Daqiqi (Persian: ابومنصور دقیقی), better simply known as Daqiqi (دقیقی), was one of the most prominent Persian poets of the Samanid era. He was the first to undertake the creation of the national epic of Iran, the Shahnameh, but came to an abrupt end in 977 after only completing 1,000 verses. His work was continued by his contemporary Ferdowsi, who would later become celebrated as the most influential figure in Persian literature.

| Native name | |

|---|---|

| Born | Abu Manṣūr Muḥammad ibn Ahmad Daqīqī c. 935 Tus, Khorasan, Samanid Empire |

| Died | 977 |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | Persian |

| Genre | Persian poetry, national epic |

| Subject | Persian revivalism |

| Notable works | Writing the story of Gushtasp in the Shahnameh |

Name

Daqiqi's personal name was Muhammad ibn Ahmad, whilst his patronymic was Abu Mansur, thus his full name being Abu Manṣūr Muḥammad ibn Ahmad Daqīqī.[1] He is generally known in sources by his pen-name, Daqiqi (meaning "accurate" in Arabic and Persian).

Background and religion

Daqiqi was born around some time after 932. Like many other Iranian grandees and scholarly of the early Middle Ages, Daqiqi was most likely born into a family of Iranian landowners (dehqans), or at least was descended from such a class.[1] During this period there was a large amount of growth in literature, mostly in poetry. It was under the Iranian Samanid Empire that Persian literature appeared in Transoxania and was formally recognized. The advancement of an Islamic New Persian literature thus started in Transoxiana and Khorasan instead of Fars, the homeland of the Persians.[2]

Daqiqi's place of birth is disputed−the cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Balkh, Marv, and Tus have been described as his birthplace; the latter seems more likely.[3] His religion belief is disputed amongst scholars. Although he had a Muslim name, this "was not in itself proof of any religious beliefs, since numerous prominent Iranian scholars and officials converted to Islam during the early Islamic period in order to maintain their means of livelihood but practised Zoroastrianism in secret" (Tafazzoli).[1] His birthplace, Tus, was at that time a predominantly Shi'ite city, and during Abu Mansur Muhammad's governorship had become the hub of Iranian nationalism. According to the Encyclopædia Iranica, it is thus likely that Daqiqi, possibly like fellow poet and Tus-native Ferdowsi, was an adherent of Shia Islam. Many Shi'ite Muslims were proud of their ancient Iranian heritage, which resulted in them being described as Qarmatians and Shu'ubis and classified as Mājūs (Zoroastrians) and Zindīq (Manicheans). Some quotations from Daqiqi's poetic verses, however, show a strong veneration towards Zoroastrianism, which have led to many scholars such as Nöldeke and Shahbazi favor a Zoroastrian origin for Daqiqi.[1] In one of Daqiqi's verses, he applauds the Zoroastrian religion as one of the four things most important to him;[1]

Daqiqi has chosen four qualities of all good and evil things in the world:

Ruby-coloured lips and the sound of the lute.

Old red wine and the Zoroastrian religion!

Biography

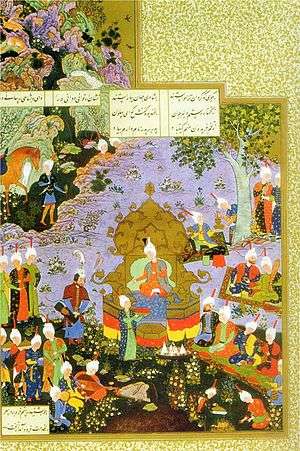

Daqiqi began his career at the court of the Muhtajid ruler Abu'l Muzaffar ibn Muhammad in Chaghaniyan, and was later invited to the Samanid court by the Samanid ruler (amir) Mansur I (r. 961–976).[4] Under the Samanids, ancient Iranian legends and heroic traditions were taken in special interest, thus inspiring Daqiqi to write the Shahnameh ("The Book of Kings"), a long epic poem based on the history of the Iranians.

He was, however reportedly murdered by his slave in 977. Only a small part of Shahnameh had been completed, which was about the conflict between Gushtasp and Arjasp.[4][5] The rapid growth of interest in ancient Iranian history made Ferdowsi continue the work of Daqiqi, completing the Shahnameh in 994, only a few years before the fall of the Samanid Empire. He later completed a second version of the Shahnameh in 1010, which he presented to the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud (r. 998–1030). However, his work was not as appreciated by the Ghaznavids as it was by the Samanids.[4]

Daqiqi's small part, which included around 1,000 verses, was maintained in the Shahnameh; his technique is more old-fashioned compared to that of Ferdowsi, and also "dry and devoid of the similes and images that are to be found in Ferdowsi's poetry" (Khaleghi-Motlagh).[3] This was mentioned in the Shahnameh by Ferdowsi, who although admired him, also criticized his poetic style, and considered it inappropriate for the national epic of Iran.[3]

References

- Williams & Stewart 2016.

- Litvinsky 1998, p. 97.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh 1993, pp. 661–662.

- Litvinsky 1998, p. 98.

- Frye 1975, p. 154.

Sources

- Frye, R. N. (1975). "The Sāmānids". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–161. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Litvinsky, Ahmad Hasan Dani (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Age of Achievement, A.D. 750 to the end of the 15th-century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231032110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Djalal (1993). "DAQĪQĪ, ABŪ MANṢŪR AḤMAD". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 6. pp. 661–662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Alan; Stewart, Sarah (2016). The Zoroastrian Flame: Exploring Religion, History and Tradition. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–400. ISBN 9780857728869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.png)