Reproductive system of gastropods

The reproductive system of gastropods (slugs and snails) varies greatly from one group to another within this very large and diverse taxonomic class of animals. Their reproductive strategies also vary greatly, see Mating of gastropods.

In many marine gastropods there are separate sexes (male and female); most terrestrial gastropods however are hermaphrodites.

Courtship is a part of the behaviour of mating gastropods. In some families of pulmonate land snails, one unusual feature of the reproductive system and reproductive behavior is the creation and utilization of love darts, the throwing of which have been identified as a form of sexual selection.[1]

Gastropods are defined as snails and slugs, belonging to a larger group called Molluscs.[2] Gastropods have unique reproductive systems, varying significantly from one taxonomic group to another. They can be separated into three categories: marine, freshwater, and land.[3] Reproducing in marine or freshwater environments makes getting sperm to egg much easier for gastropods, while on land it is much more difficult to get sperm to egg.[4] The majority of gastropods have internal fertilization, but there are some prosobranch species that have external fertilization.[5] Gastropods are capable of being either male or female, or hermaphrodites, and this makes their reproduction system unique amongst many other invertebrates. Hermaphroditic gastropods possess both the egg and sperm gametes which gives them the opportunity to self-fertilize.[5]

Reproductive system of marine gastropods

The reproductive system of marine gastropods such as those from class Opisthobranchia and order Archaeogastropoda from the class Prosobranchia, is a continuous cycle of alternating male and female reproductive role prevalence. Immediately after spawning in late summer, the predominance of the female reproductive functions are terminated and gametogenesis initiates immediately, with the start of the predominance of the male reproductive role. Gametes remain in the gonads throughout the winter and early spring. The female reproductive role takes over again in May with fertilization of the gametes to form zygotes. The cycle comes full circle in late summer once again, with spawning.[6]

Separate sexes

In many taxonomic groups of marine gastropods, there are separate sexes (i.e. they are dioecious).

In some of the main gastropod clades the great majority of species have separate sexes. This is true in most of the Patellogastropoda, Vetigastropoda, Cocculiniformia, Neritimorpha, and Caenogastropoda.

Protandrous sequential hermaphrodites

Within the clade Littorinimorpha however, the superfamily Calyptraeoidea are protandrous sequential hermaphrodites. Protandry means that the individuals first become male, and then later on become female. See for example the genus Crepidula.

Simultaneous hermaphrodites

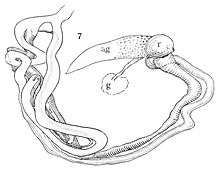

Within the main clade Heterobranchia, the informal group Opisthobranchia are simultaneous hermaphrodites (they have both sets of reproductive organs within one individual at the same time).

There are also a few marine pulmonates, and these are also hermaphroditic, for example, see the air-breathing sea slug family Onchidiidae, and the family of air-breathing marine "limpets" Siphonariidae.

Reproductive system of land gastropods

Separate sexes

Although most land snails are pulmonates and are hermaphrodites, in contrast, all of the land-dwelling prosobranch snails are dioecious (in other words, they have separate sexes). This includes the snails in the families Pomatiidae, Aciculidae, Cyclophoridae, and others. These land snails have opercula, which helps identify them as "winkles gone ashore", in other words, snails within the clade Littorinimorpha and the informal group Architaenioglossa.

Members of the snail family Pulmonata, which includes carboniferous land sails and some freshwater snails of the order Basommatophora, are protandrous hermaphrodites, meaning they are born male and later in life become female. In this family of snails, the male phase ends in December, followed by an egg maturation phase, and ends with oviposition, the act of laying eggs during May of the following year. Phylogenetic evidence for this is present based on the overall condition of the gonads especially in the degree of development of the genital ducts.[7]

Simultaneous hermaphrodites

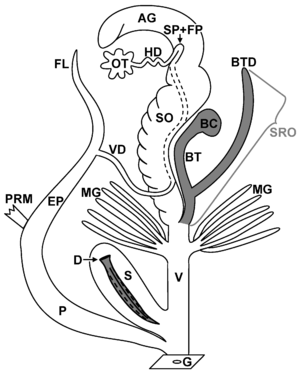

AG = albumen gland

BC = bursa copulatrix

BT = bursa tract/trunk

BTD = bursa tract diverticulum

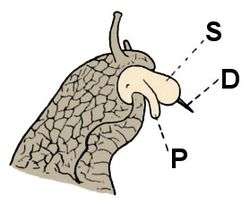

D = love dart

EP = epiphallus

FL = flagellum

FP = fertilization pouch

G = genital pore

HD = hermaphroditic duct

MG = mucus glands (nidamental gland)

OT = ovotestis

P = penis

PRM = penis retractor muscle

S = stylophore or dart sac (bursa telae)

SO = spermoviduct

SP = spermathecae

SRO = spermatophore-receiving organ (indicated in grey)

V = vagina

VD = vas deferens

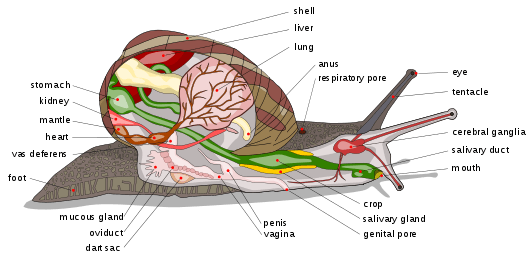

Pulmonate land gastropods are simultaneous hermaphroditic and their reproductive system is complex. It is all completely internal, except for genital protrusion (eversion) during mating. The outer opening of the reproductive system is called the "genital pore"; it is positioned on the right-hand side, very close to the head of the animal. This opening is virtually invisible, however, unless it is actively in use.

The love-dart (if present) is produced and stored in the stylophore (often called dart sac) and shot by a forceful eversion of this organ. The mucus glands produce the mucus that is deposited on the dart before shooting. The penis is intromitted to transfer the spermatophore. The sperm container is formed in the epiphallus, while the spermatophore's tail is formed by the flagellum. When a bursa tract diverticulum is present, the spermatophore is received in this organ. Together with the bursa tract and bursa copulatrix these form the spermatophore-receiving organ, which digest sperm and spermatophores. Sperm swim out via the tail of the spermatophore to enter the female tract and reach the sperm storage organ (spermathecae) within the fertilization pouch-spermathecal complex.[8]

Variability (polymorphism) of reproductive system in stylommatophorans is common feature.[9] Such variability may include:[9]

- euphallics = male copulatory organs have developed as usual

- hemiphallics = male copulatory organs are reduced

- aphallics = no male copulatory organs develop

also

- in Heterostoma paupercula the epiphallus and flagellum can be either present or absent

- in Arion distinctus there is usually a bipartite oviduct, but there is sometimes a tripartite free oviduct

- in Fruticicola fruticum there is a variable number of mucous gland lobes in the auxiliary copulatory organs

Examples of reproductive system of various land snails:

The structure of the reproductive system is strictly hermaphroditic. From the gonads, a hermaphrodite duct, a duct which is designed to transport both sperm and eggs, leads to a portion of the reproductive tract where the duct splits into a strictly male and strictly female portion.[7]

The female portion includes a fertilization pouch and posterior and anterior mucus glands, which open up into a pallial cavity which leads to a small muscular vagina. The male portion of the reproductive tract includes both a short posterior vas deferens and a longer anterior vas deferens. The posterior vas deferens is followed by the prostate, and the anterior vas deferens flows through the haemocoele, an enlarged blastula filled with blood, of the head and opens into a muscular penis which is engulfed in a small portion of skin called the prepuce sac.[7]

Reproductive system in freshwater gastropods

Separate sexes and hermaphrodites

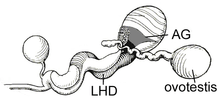

Species in the freshwater gastropod family such as the Caenogastropoda from the class Prosobranchia, are largely self-fertilizing; however after many generations of selfing, a physiological barrier halts sperm generation in that organism, and only allows for the introduction of foreign sperm. Gametes form in the ovotesties, an organ which produces both ova and sperm, and pass down into the hermaphroditic duct to the albumen gland, the junction of where the common duct splits to either vas deferens or oviduct, where they are stored until they are needed for either mating or self-fertilization. It is believed that this junction acts as a regulatory mechanism via contracting muscles, to help direct sperm or eggs into the correct ducts.[10]

Mating

The sperm passes into the male duct, or vas deferens, where is receives secretory additions in the form of mucus from the prostate. After getting modified, the sperm passes into the penis. During mating season, the glandular cells in the penis sheath and prepuce swell to facilitate eversion of the penis. The sperm gets pushed through the penis, where they are introduced into the tail end of its copulatory partner. Within the partner snail, after fertilization from the foreign sperm, the eggs pass into the albumen gland where they are coated in mucus which forms the egg capsule.[10]

Selfing

Eggs are released immediately before oviposition. Unlike in land gastropod species where fertilization occurs in fertilization pockets, fertilization in freshwater species happens at the lower end of the hermaphroditic duct, near the junction. Sperm is deposited into the bursa copulatrix which opens up into the vagina. The ova then enter the albumen gland to get a nutrient dense mucus coating which serves to form the egg capsule.[10]

Genital structures

Genital structures in Stylommatophora include (English name and Latin/Greek name is after the hyphen):

- albumen gland - glandula albuginea[11]

- atrium - atrium / vestibulum[11]

- bursa copulatrix - bursa copulatrix[11]

- dart sac - bursa teloris[11]

- diverticulum - diverticulum[11]

- epiphallar caecum - epiphallus caecum[11]

- epiphallus - epiphallus[11]

- fertilisation pouch - camera fertilis[11]

- flagellum - flagellum[11]

- genital aperture - apertura genitalis[11]

- hermaphroditic duct - ductus hermaphroditicus[11]

- hermaphroditic gland - glandula hermaphroditica, ovotestis[11]

- love dart - spiculum amoris[11]

- mucous glands, digitiform glands - glandulae mucosae[11]

- pedunculus - pedunculus[11]

- penial appendix - appendix[11]

- penial caecum - caecum[11]

- penial papilla - penis papilla[11]

- penial sheath - penis capsula[11]

- penis - penis / phallus[11]

- retractor muscle of the appendix - musculus retractor appendicis[11]

- retractor muscle of the penis - musculus retractor penis[11]

- retractor muscle of the vagina - musculus retractor vaginae[11]

- spermatophore - spermatophora[11]

- spermoviduct - spermoviductus[11]

- prostate - pars prostetica[11] = a gland related to male part of the reproductive system

- uterus - pars uterica[11]

- stimulatory organ - appendicula[11]

- vagina - vagina[11]

- vas deferens - vas deferens / ductus deferens[11]

Genital structures of males

The prostate is found in the mantle tubule and penis are both connected to the gonoduct; which are connected to the testis (produce sperm). During sex, the sperm travels along the mantle tube in which seminal fluid fills the mantle tube and exits the body via the penis and enters the females gonopore.[12]

Additional reproductive structures include

- Vas deferens: it is found attached to the penis and the prostate and aids in the movement of sperm from the prostate to the penis[12]

- Dart sac: helps males grasp onto females during sex. Not found in all gastropods[12]

Genital structures of females

Females have a gonopore that is connected to a seminal receptacle. The gonopore acts as an opening through which eggs are deposited. The opening leads into the mantle tubule, in which eggs flow from the oviduct and ovary. The mantle tubule produces three things, yolk; carries most of the nutrients needed to develop a healthy offspring, egg capsule formation, and sperm reception and storage; where fertilization occurs. After fertilization, eggs travel to the albumin glands to fill the yolk with protein, and lastly, the egg travels through the capsule glands, which coat the egg in a protective jelly.[12]

Additional reproductive structures include:

Genital structures of hermaphrodites

Hermaphrodites have both male and female reproductive parts. The male and female system act as separate units until the egg and sperm are ready to fuse together. The fusion of egg and sperm takes place in the uterus of the female system. Hermaphrodites also have a hermaphroditic duct, which helps change the sex of the gastropod during certain times of the year.[12]

See also

- Mating of gastropods

- Apophallation

- Reproductive system of mollusks

- Reproductive system of cephalopods

References

This article incorporates CC-BY-2.0 text (but not under GFDL) from the reference[8]

- Tales of two snails: sexual selection and sexual conflict in Lymnaea stagnalis and Helix aspersa Oxford Journals

- "Gastropoda - slugs and snails". www.ento.csiro.au. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- "An Overview of the Life Cycle of a Gastropod". Bright Hub Education. 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- "Snails and Slugs (Gastropoda)". www.molluscs.at. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- Nakadera, Yumi; Koene, Joris M. (2013-03-25). "Reproductive strategies in hermaphroditic gastropods: conceptual and empirical approaches". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 91 (6): 367–381. doi:10.1139/cjz-2012-0272. ISSN 0008-4301.

- "Springer Shop". www.springer.com. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- Morton, J. E. (1955-11-03). "The Functional Morphology of the British Ellobiidae (Gastropoda Pulmonata) with Special Reference to the Digestive and Reproductive Systems". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 239 (661): 89–160. doi:10.1098/rstb.1955.0007. ISSN 0962-8436.

- Joris M. Koene & Hinrich Schulenburg. 2005. Shooting darts: co-evolution and counter-adaptation in hermaphroditic snails. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 2005, 5:25 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-25.

- Backeljau T. et al. Population and Conservation genetics. in Barker G. M. (ed.): The biology of terrestrial molluscs. CABI Publishing, Oxon, UK, 2001, ISBN 0-85199-318-4. 1-146, pages 389-390.

- Duncan, C. J. (1958-07-01). "The Anatomy and Physiology of the Reproductive System of the Freshwater Snail Physa Fontinalis (l.)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 131 (1): 55–84. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1958.tb00633.x. ISSN 1469-7998.

- (in Hungarian) Páll-Gergely B. (2008). "A Stylommatophora csigák ivarszervrendszerének magyar nyelvű nevezéktana". Malacological Newsletter 26: 37-42. PDF.

- Barth, Robert; Broshears, Robert (1982). The Mollusks. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders College Publishing.