Earconwald

Earconwald or Erkenwald[lower-alpha 1] (died 693) was Bishop of London between 675 and 693.

Earconwald | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of London | |

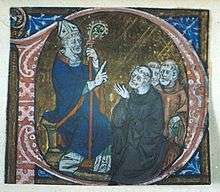

Earconwald teaching monks in a historiated initial from the Chertsey Breviary (c.1300) | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Installed | 675 |

| Term ended | 693 |

| Predecessor | Wine |

| Successor | Waldhere |

| Other posts | Abbot of Chertsey |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | c. 675 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | circa 630 Kingdom of Lindsey |

| Died | 693 Barking Abbey |

| Buried | Old St Paul's Cathedral, London |

| Denomination | Christianity |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 13 May 24 April 30 April 14 November in England |

| Attributes | bishop in a small chariot, which he used for travelling his diocese; with Saint Ethelburga of Barking |

| Patronage | against gout, London |

| Shrines | St. Paul's, London |

Life

Earconwald was born at Lindsey in Lincolnshire,[1] and was supposedly of royal ancestry.[2] Earconwald gave up his share of family money to help establish two Benedictine abbeys, Chertsey Abbey in Surrey[3] in 666 for men, and Barking Abbey for women.[1][4] His sister, Æthelburg, was Abbess of Barking,[1][5] while he served as Abbot of Chertsey.[6]

In 675, Earconwald became the Bishop of London, after Wine.[7] He was the choice of Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury.[6] While bishop, he contributed to King Ine of Wessex's law code, and is mentioned specifically in the code as a contributor.[8] He is also reputed to have converted Sebba, King of the East Saxons to Christianity in 677. Current historical scholarship credits Earconwald with a large role in the evolution of Anglo-Saxon charters, and it is possible that he drafted the charter of Caedwalla to Farnham.[5] King Ine of Wessex named Earconwald as an advisor on his laws.[9]

Earconwald died in 693[7] and his remains were buried at Old St Paul's Cathedral. His grave was a popular place of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, and was destroyed together with a number of other tombs in the cathedral during the Reformation.[10]

Earconwald's feast day is 30 April, with translations being celebrated on 1 February and 13 May.[2] He is a patron saint of London.[11]

See also

Notes

- Also Ercenwald, Eorcenwald or Erconwald

Citations

- Walsh A New Dictionary of Saints p. 182

- Farmer Oxford Dictionary of Saints p. 175

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 83

- Yorke "Adaptation of the Anglo-Saxon Royal Courts" Cross Goes North pp. 250–251

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 102

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 95–96

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 219

- Yorke Conversion of Britain p. 235

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 103

- Thornbury Old and New London: Volume 1 p. 248

- Farmer Oxford Dictionary of Saints p. 494

References

- Farmer, David Hugh (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860949-0.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Thornbury, Walter (1887). Old and New London. Volume 1. London: Cassell.

- Walsh, Michael J. (2007). A New Dictionary of Saints: East and West. London: Burns & Oats. ISBN 0-86012-438-X.

- Yorke, Barbara (2003). Martin Carver (ed.). The Adaptation of the Anglo-Saxon Royal Courts to Christianity. The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300–1300. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 244–257. ISBN 1-84383-125-2.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-77292-3.