Felix of Burgundy

Felix of Burgundy, also known as Felix of Dunwich (died 8 March 647 or 648), was a saint and the first bishop of the East Angles. He is widely credited as the man who introduced Christianity to the kingdom of East Anglia. Almost all that is known about the saint originates from The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed by Bede in about 731, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Bede praised Felix for delivering "all the province of East Anglia from long-standing unrighteousness and unhappiness".

Felix | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of the East Angles | |

Felix of Burgundy, as depicted in the reredos in St Peter Mancroft, Norwich | |

| See | Diocese of Dommoc |

| Appointed | c. 630 |

| Term ended | c. 648 |

| Successor | Thomas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Burgundy |

| Died | 8 March 647 or 648 Dunwich |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 8 March |

| Venerated in | Church of England[1], Eastern Orthodox Church, Roman Catholic Church |

| Attributes | bishop with three rings on his right hand |

Felix, who originated from the Frankish kingdom of Burgundy, may have been a priest at one of the monasteries in Francia founded by the Irish missionary Columbanus: the existence of a Bishop of Châlons with the same name may not be a coincidence. Felix travelled from his homeland of Burgundy to Canterbury before being sent by Honorius to Sigeberht of East Anglia's kingdom in about 630, (by sea to Babingley in Norfolk, according to local legend). On arrival in East Anglia, Sigeberht gave him a see at Dommoc (possibly Walton, Suffolk or Dunwich in Suffolk). According to Bede, Felix helped Sigeberht to establish a school in his kingdom "where boys could be taught letters". He died on 8 March 647 or 648, having been bishop for seventeen years. His relics were translated from Dommoc to Soham Abbey and then to the abbey at Ramsey.

After his death, Felix was venerated as a saint: several English churches are dedicated to him. Felix's feast date is 8 March.

Background and early life

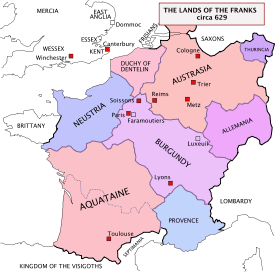

Felix came from the Frankish kingdom of Burgundy, although his name prevents historians from conclusively identifying his nationality.[2][3] According to Bede, he was ordained in Burgundy.[4]

It is possible that Felix was associated with Irish missionary activity in Francia, which was centred in Burgundy and was particularly associated with Columbanus and Luxeuil Abbey.[3] Columbanus had arrived in Francia in about 590,[5] after leaving Bangor along with twelve companions and going into voluntary exile. Upon Columbanus's arrival, he was encouraged to stay, and in about 592 settled at Annegay, but was then forced to find an alternative site for a monastery at Luxeuil, when lay people and the sick continually sought the counsel of himself and his fellow monks.[6]

The connection between the Wuffingas ruling dynasty and the abbess Burgundofara at Faremoutiers Abbey was an example of the associations that existed at the time between the Church in East Anglia and religious establishments in Francia. Such associations were partly due to the work of Columbanus and his disciples at Luxeuil: together with Eustasius, his successor, Columbanus inspired Burgundofara to found the abbey at Faremoutiers. It has been suggested that a connection between the disciples of Columbanus, (who strongly influenced the Christians of Northern Burgundy) and Felix, helps to explain how the Wuffingas dynasty established its links with Faremoutiers.[7] Higham notes various suggestions for where Felix may have originated, including Luxeuil, Châlons or the area around Autun. Other historians have made connections between Felix and Dagobert I, who had contact with both King Sigeberht of East Anglia and Amandus, a disciple of Columbanus.[8]

McLure and Collins note that there was a bishop named Felix who held the see of Châlons in 626 or 627. They suggest the possibility that Felix may have become a political fugitive as a result of losing his see at Châlons after the death of Chlothar II in 629.[9]

Arrival in the kingdom of the East Angles

Felix is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals that was compiled in the late ninth century. The annal for 633 in 'Manuscript A' of the Chronicle, states that Felix "preached the faith of Christ to the East Angles". Another version of the Chronicle, 'Manuscript F', written in the eleventh century in both Old English and Latin, elaborates upon the short statement contained in the Manuscript A annal:

- "Here there came from the region of Burgundy a bishop who was called Felix, who preached the faith to the people of East Anglia; called here by King Sigeberht; he received a bishopric in Dommoc, in which he remained for seventeen years."[10][11]

Bede describes how the exertions of King Sigeberht of East Anglia "were nobly promoted by Bishop Felix, who, coming to Honorius, the archbishop, from the parts of Burgundy, where he had been born and, ordained, and having told him what he desired, was sent by him to preach the Word of life to the aforesaid nation of the Angles".[12] Later sources tend to differ from the version of events described by Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The Liber Eliensis, an English chronicle and history written at Ely Abbey in the 12th century, states that Felix came with Sigeberht from Francia and was then made Bishop of East Anglia.[13] According to another version of the story, Felix travelled from Gaul and reached the hamlet of Babingley, via the River Babingley. He then made his way to Canterbury. He was ordained as a bishop in about 630 or 631[14] by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Honorius.[15]

Felix's arrival in East Anglia seems to have coincided with the start of a new period of order established by Sigeberht, that had followed the assassination of Eorpwald and the three years of apostasy that followed Eorpwald's murder. Sigeberht had become a devout Christian before returning from exile in Francia to become king. His accession may have been decisive in bringing Felix to East Anglia.[2] Peter Hunter challenges the assertion by mediaeval sources that spoke of Felix and Sigeberht travelling together from Francia to England, as in his view Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People implied that Felix went to East Anglia because of Honorius at Canterbury.[3]

Bishop of the East Angles

Soon after his arrival at Sigeberht's court, Felix established a church at Dommoc, his episcopal see, which is widely taken to mean Dunwich, on the Suffolk coast. Dunwich has since been almost totally destroyed by the effects of coastal erosion. Other historians have suggested as an alternative site for Felix's see the coastal Walton, Suffolk near Felixstowe, where there was once a Roman fort, Walton Castle, since washed away by the sea. A church and priory were dedicated to him there by Roger Bigod in 1105.

Bede related that Felix started a school, "where boys could be taught letters", to provide Sigeberht with teachers.[16] There is no evidence that Felix's school was at Soham, as is maintained by later sources.[2] Bede is unclear as to the origin of the teachers at the school that was established, who may have been from Kent itself or similar to those who were to be found in Kent.[3] The Liber Eliensis mentioned that he also founded the abbey at Soham, in Cambridgeshire and a church at Reedham in Norfolk: "Indeed, one reads in an English source that St Felix was the original founder of the old monastery of Sehem and of the church at Redham".[17] According to Margaret Gallyon, the large size of the East Anglian diocese would have made the foundation of a second religious establishment at Soham "appear very probable".[18]

During his years as bishop, the East Anglian Church was made still stronger when Fursey arrived from Ireland and founded a monastery, at Cnobheresburg, probably located at Burgh Castle, in Norfolk.[19]

Death and veneration

Felix died in 647 or 648, after he had been bishop for seventeen years.[20] After his death, which probably occurred during the reign of Anna of East Anglia,[2] Thomas, a Fenman, became the second Bishop of the East Angles. Felix was buried at Dommoc, but his relics were at a later date removed to Soham, according to the twelfth-century English historian William of Malmesbury. His shrine was desecrated by the Vikings when the church was destroyed. Some time later, "the body of the saint was looked for and found, and buried at Ramsey Abbey".[19][21] Ramsey was noted for its enthusiasm for collecting saints' relics,[22] and in an apparent attempt to out-compete their rivals from the abbey at Ely, the Ramsey monks escaped by rowing their boats through thick Fenland fog, carrying with them the bishop's precious remains.[23]

Felix's feast day is celebrated on 8 March.[2] There are six churches dedicated to the saint, located in North Yorkshire and East Anglia. According to the mediaeval Custumal of Bury St Edmunds, known as the Liber Albus, Felix is said to have visited Babingley, in the northwest of Norfolk, and 'maden... ... the halige kirke' – "built the holy church".[24]

The village of Felixkirk (in Yorkshire) and the town of Felixstowe may both have been named after the saint, though an alternative meaning for Felixstowe, "the stow of Filica", has been suggested.[2][25]

References

- Church of England, Common Worship, The Calendar

- Costambeys, Marios, "Felix [St Felix] (d. 647/8), bishop of the East Angles", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 25 June 2011

- Blair, The World of Bede, p. 108.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book II, Chapter 15.

- Lapidge, Columbanus, p. 2.

- Lapidge, Columbanus, p. 8-10.

- Wood et al., People and Places in Northern Europe, p.8.

- Higham, The Convert Kings, p. 199, note 11.

- McLure and Collins, Explanatory notes, in The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, p. 381-2.

- Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, p. 26.

- Baker, The Anglo-Saxon chronicle: MS F, p. 33: [636] Hic Cuicelm rex baptizatus est. 'Hic de Burgeindie partibus uneit 'episcopus' quidam nomine Felix, qui predicauit fidem populous Orientalium Anglorum; hic accersitus a Sigeberto rege, suscipit episc(o)patum in Domuce, in quo sedit .xvii. annis.' .

- Bede, Book II, chapter 15.

- Fairweather, Liber Eliensis, p. 13.

- Fryde et al., Handbook of British Chronology, p. 216.

- Walsh, A New Dictionary of Saints, p. 201.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book III, chapter 18.

- Fairweather, Liber Eliensis, p. 20.

- Gallyon, The Early Church, p. 61.

- Butler, Lives of the Saints, p. 74.

- Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 66.

- Preest, The Deeds of the Bishops of England, p. 96.

- Preest, The Deeds of the Bishops of England, p. 215, note 2.

- DeWindt and DeWindt, Ramsey, pp. 53, 308 (note 64).

- Pestell, Landscapes of Monastic Foundation, p. 97.

- Ekwall, English Place-names, p. 177.

Sources

- Baker, Peter S. (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition, volume 8: MS. F. Bury St Edmunds: St Edmundsbury Press. ISBN 0-85991-490-9.

- Blair, Peter Hunter (2001). The World of Bede. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39819-3.

- Butler, Alban (1999). Butler's Lives of the Saints (March). Collegeville: The Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-2379-4.

- DeWindt, Anne Reiber; DeWindt, Edwin Brezette (2006). Ramsey: The Lives of an English Fenland Town, 1200-1600. 1. Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 0-8132-1424-6.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-869103-3.

- Fairweather, Janet (trans.), ed. (2005). Liber Eliensis. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-015-3.

- Gallyon, Margaret (1973). The Early Church in Eastern England. Terence Dalton. ISBN 0-900963-19-0.

- Higham, N. J. (1997). The convert kings: power and religious affiliation in early Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4828-1.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Matthew, Colin, ed. (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- Bede (1994). McClure, Judith; Collins, Roger (eds.). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283866-0.

- Pestell, Tim (2004). Landscapes of monastic foundation: the establishment of religious houses in East Anglia c.650-1200. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-84383-062-0.

- Preest, David (2002). William of Malmesbury's The Deeds of the Bishops of England. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-884-6.

- Swanton, Michael (1997). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Walsh, Michael (2007). A New Dictionary of Saints: East and West. London: Burns & Oates. ISBN 0-86012-438-X.

- Wood, Ian; Lund, Neils; Sawyer, Peter Hayes (1996). People and Places in Northern Europe, 500-1600; Essays in Honour of Peter Hayes Sawyer. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 0-85115-547-2.

Fiction

- Gray, Arthur; Swain, E. G. (2010). "The Palladium". Ancient Haunts: The Stoneground Ghost Tales / Tedious Brief Tales of Granta. Landisville: Coachwhip Publications. pp. 198–205. ISBN 978-1-61646-005-1.